Two achievements and two failures define Woodrow Wilson’s presidency. Historians have spilled rivers of ink debating whether the former outweigh the latter. Wilson’s domestic achievement was to pass a major legislative program called the New Freedom, featuring progressive taxation, antitrust laws, tariff reduction, and the creation of the Federal Reserve system. His domestic failure was a profound disregard for Americans’ civil rights and civil liberties. Wilson’s administration formally segregated the federal civil service by race and passed draconian wartime sedition laws; his attorney general, A. Mitchell Palmer, chased dissenters during the Red Scare.

Yet this domestic tally tells us less about Wilson than the cold record suggests. He enjoyed strong Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress during his first term, easing passage of his legislative agenda. His views on race were, if lamentable, very much in keeping with the times; and it should be noted that Palmer led his witch hunts while Wilson was incapacitated by a stroke. Thus the true measure of his success or failure lies in the realm of foreign policy.

Here Wilson’s achievement was to lead the United States into World War I. He refrained from intervening in Europe’s war for as long as possible, but then intervened with purpose, sending doughboys and America’s mighty Navy across the Atlantic at a critical moment in the campaign. The move proved decisive: as military historian John Keegan writes in his authoritative The First World War, “Rare are the times in a great war when the fortunes of one side or the other are transformed by the sudden accretion of a disequilibrating reinforcement.”

The experience turned the United States into a world power and established the hallmarks of its foreign policy: solidarity with the Atlantic allies, a moral component to international decision making, and a commitment to global institutions. The word “idealism” is often associated with Wilson’s name, and for good reason: World War I marked the point at which the United States began acting abroad on the basis of principles in addition to interests. This worldview is dismissed as a sham by many other countries and has produced some of our thorniest problems in the past twenty years—Rwanda and the Balkans in the 1990s, Iraq in the 2000s, and now Syria. But that does not necessarily invalidate liberal internationalism or detract from Wilson’s vision.

Yet his major foreign policy failure followed directly from American involvement in the war. Wilson expended great capital negotiating the Treaty of Versailles, which set the terms of peace and, on Wilson’s insistence, contained the League of Nations covenant. But the U.S. Senate refused to ratify the treaty. The League of Nations was Wilson’s baby—the fourteenth of fourteen points he drafted to end the war—and its rejection was a crushing humiliation from which he never recovered. Wilson completed the final year and a half of his presidency a bitter and broken man. Although the League offered a template and structure for the United Nations, it failed to keep the peace that the Allies so painstakingly negotiated at Paris in 1919.

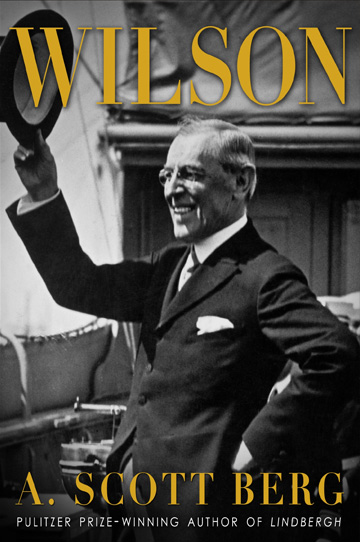

A major new biography by Pulitzer Prize winner A. Scott Berg reveals how Wilson’s personality contributed to his failures in office. Woodrow Wilson was “a man of flagrant morality,” Berg writes. To put it less charitably, he was grandiloquent, tempestuous, self-righteous, and stubborn to the point of pigheadedness. Berg’s pages overflow with Wilson’s grudges and excommunications; “The President is a wonderful hater,” remarked French Prime Minister Georges Clémenceau, who tangled with him in Paris. The British diplomat Harold Nicholson wrote that Wilson’s “spiritual and mental rigidity” was his undoing. “It rendered him as incapable of withstanding criticism as of absorbing advice. It rendered him blind to all realities which did not accord with his preconceived theory.”

A bit strong? Consider Wilson’s comments to William McCombs, the chairman of his campaign committee, on election night in 1912. “Before we proceed, I wish it clearly understood that I owe you nothing. God ordained that I should be the next president of the United States. Neither you nor any other mortal could have prevented that.” Or consider his righteous indignation at the way Senate Republicans outmaneuvered him at the close of the war: “I have seen fools resist Providence before and I have seen the destruction, as will come upon these again—utter destruction and contempt. That we shall prevail is as sure as that God reigns.” Sigmund Freud was not the only man to diagnose the president with a Christ complex.

Wilson’s frightful messianism infused his determination to advance the League of Nations at the Paris Peace Conference. Other heads of government muttered that establishing the League really had very little to do with the business of concluding the war. The clever allies even used Wilson’s single-mindedness as leverage, extracting concessions as the price of their support for the League: in this way Britain secured Wilson’s agreement to try Kaiser Wilhelm II, and France solidified its claim to occupy the Rhenish Republic. Back home, Wilson probably could have won ratification of the Versailles Treaty if only he had compromised with moderate senators. But he would not budge, insisting that any change to its terms would stain the nation’s honor. “The President has strangled his own child,” observed one baffled senator before the final vote.

It is difficult to reconcile Wilson’s difficult personality with the great esteem in which Americans held and continue to hold him. Berg covers much ground, but surprisingly does not identify this contradiction. The truth is, Wilson is beloved because he was that rarest of breeds: a principled politician. Who wouldn’t like a president with some spine—it is why we watched The West Wing. Moreover, one notices again and again in Wilson that the man’s principles were usually right. He alone at Versailles argued from the outset that harsh terms against Germany would only precipitate another war. His domestic agenda was filled with much-needed progressive reforms. While president of Princeton, he led a campaign for merit over privilege, turning the university from a brats’ club into a prestigious research institution. And on the Versailles Treaty, Wilson was right that Senate Republicans merely wanted to score political points and undercut his prestige. In fact, Berg shows that they decided to scupper the treaty before it was even written.

But a principled politician can resemble a stampeding elephant: nothing will stand in his way, and eventually he ends up lost with two broken tusks. Wilson ran himself ragged in support of the treaty, and died bewildered and angry that all had gone wrong. Professor Joseph Nye recently observed that Wilson’s presidency resembles George W. Bush’s: high moralism, big risks, more vision than execution. And Wilson’s stubborn insistence on establishing the League at Versailles echoes Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld’s push to streamline the military during the Iraq War. Others disagreed, circumstances changed, it wasn’t the right time—but the secretary forged on. Moreover, Wilson’s utter refusal to compromise over the Versailles Treaty sounds like nothing in politics today so much as Tea Party intransigence. That Wilson was debilitated by illness during the last phase of the treaty debate is some excuse, but he showed little flexibility even while he was well.

Berg’s Wilson offers an intimate portrait of this aloof president. John Milton Cooper’s Woodrow Wilson (2009) is more focused and sharply analyzed, but contains less detail on Wilson the man. Berg is particularly strong in narrating certain dramatic set pieces: the cabinet meeting that led to war; the address to Congress asking for a declaration; the whistle-stop tour in support of the treaty; the stroke that ultimately incapacitated him. (That is one area where Wilson’s judgment—or that of his inner circle—was not infallible. It was a disservice to the country that Wilson lingered in office for a year and a half rather than resigning.)

Nevertheless, the book does have its faults. Although Berg appropriately criticizes Wilson for the Red Scare and for rigidity over the League, he at times gets caught up in the mystique of the professor-president in the top hat and pince-nez. This enchantment manifests itself in an inordinate number of superlatives: in Paris Wilson received “the most massive display of acclamation and affection ever heaped on a single human being”; of the League, “No man had ever gone to such lengths for a cause”; Wilson’s letters to his wife comprised “one of the most expansive love correspondences in history.” When Berg is not coming up with sentences like these, he is quoting like-minded stuff from others. The effect is to make the reader question his judgment. It is a small detraction from a very good book, but it is more than mere semantics. Something about Woodrow Wilson causes us to get carried away—to elide the details and embrace the man of vision and big ideas. Sometimes a politician must take a stand: few voters will support a candidate who won’t. But Wilson is the president who stood and stood until he fell down on his face. Sometimes a politician needs to compromise.