“We’re going through Dad’s bookshelves and wondered if you’d like us to save some things for you?” This innocent question, posed by phone in the fortnight between my father’s death and his memorial service, was one more weight stacked on my heart. I had been at his bedside for his final days, hours and breaths, and would be returning soon to help my mother and siblings plan the service. For the moment I was at home in Chicago, and temporarily free of the mechanics of death, if not free of grief. My brother happened to call while I was running up and down the local high-school football stadium’s stairs to clear my head. “Send me pictures,” I replied, stalling. I would take a look.

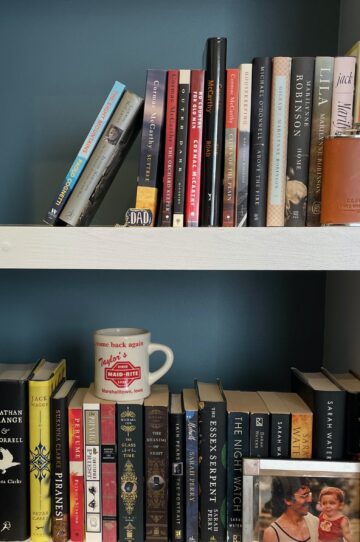

Books lined my father’s walls, just as they line my own. He taught me to love the written word as well as the printed and bound volumes themselves. However they appear—organized or hodgepodge, decorative or functional, dusty, clean, new, old—books on shelves form the wallpaper of a reader’s life. Here assembled are a person’s interests, escapes, ambitions and dreams. Their spines can be taken in at a glance, even as their contents represent the work of a lifetime. I often find myself in my own study lost in reverie, staring at the beautiful kaleidoscope and marveling at all it contains. Occasionally this musing distracts me from an open book on my lap.

The library of a departed loved one is like clothing or a pair of glasses: It allows his or her presence to be felt for just a bit longer. Yet it extends the reach of his mind and not just his person. My dad’s books compressed a life of quiet reflection into a physical space in the next room. His evergreen interest in our ancestral home of Ireland was well represented, from the novels of Roddy Doyle to the memoirs of Frank McCourt. So too his favorite nonfiction authors, the gentle Oliver Sacks and the wide-ranging Simon Winchester. As age and cognitive decline took their toll, the titles he went to more frequently became simpler. Henning Mankell thrillers were apparently easy to follow, and Dad read through them and stacked them neatly. I can’t count the number of times he revisited Edward Rutherford’s Sarum, or James Herriot’s stories about rural veterinary care in England. My father’s favorite uncle had been a veterinarian.

One of my father’s loveliest habits was to make the interests of his family members his interests too. When I returned to my parents’ house to begin browsing the books on his shelves, I was moved to see the history of my own enthusiasms reflected back at me. Here was Robert Caro’s The Passage of Power (2012), the latest in his chronicle of Lyndon Johnson’s career—a book my father had taken up when I went through a Caro phase that yielded a long magazine piece a decade ago. Nearby sat Edward Lazarus’s Closed Chambers (1998), about the mysteries of clerking for judges. It had motivated my own hunt for a clerkship as I finished law school. Sometimes it was difficult to trace the genesis of a pursuit, as when I came across a copy of Alfred Lansing’s Endurance (1959), the chronicle of Shackleton’s famous voyage to the Antarctic. Had Dad given it to me first, or I to him? If a father dies and his son keeps reading aloud, does it make a sound?

One book I particularly hoped to find was a fine edition of Lost Horizon (1933) that I had given my dad as a gift two years earlier. James Hilton’s old-fashioned adventure tale about the myth of Shangri-La was his favorite novel. I had found a copy bound in red leather with a silk bookmark and endpapers, published by the Franklin Library. Turning to the inscription, I saw my own handwriting. “Dad, thanks for giving me my love of books. Happy 75th birthday. Love, Michael.” My mother had already set it aside and it was waiting on the mantel when I came home.

Not every volume held such significance, of course. My father was a professor and he discarded little. It would be impracticable to keep all of his books around indefinitely. I owned many of the titles on his shelves, so carrying them home would leave me with piles of duplicates. One picture that my brother sent me contained a series of ancient paperbacks whose musty scent seemed to reach me through the phone screen. Shakespeare, Milton, Darwin: I had all of these myself. I attached sentiment to his paperback set of Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy, which I had borrowed and read for a high-school paper, and to his copy of The Hobbit, (1937) which had introduced me to Tolkien. But avoiding doubles was a clear, enforceable line of demarcation. It was also a way to start letting go.

Literature featured prominently at the memorial service. My wife read from Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead (2004), a novel set in my father’s home state of Iowa, which Ms. Robinson elsewhere describes as a “modest, open, sunny place, at peace with itself.” The passage dealt with the ephemeral nature of memories, and indeed of life, which “has its own mortal loveliness.” The narrator fondly recalls seeing his wife for the first time as she stepped into his church to avoid the rain. Ms. Robinson writes that “a moment is such a slight thing” and, in a luminous turn of phrase, gestures at the gratitude we feel for such a memory: “its abiding is a most gracious reprieve.” Simply to gather together and recall my father’s life—itself a slight thing, weighed against the fullness of time—was a reprieve of its own.

In the end I took only a few books with me. Lost Horizon. A work on cartography. My father’s own self-published and beautifully bound volume outlining the family genealogy. A few others. The rest will be donated as my mother sees fit. I can no longer keep all of these objects near me, just as I can no longer enjoy his embrace, his smile, the touch of his hand. He is gone. Reverence for print and the beauty and knowledge it holds: This is the reading legacy of a departed parent to his bereft child. Not the books themselves. Someone else will read them. And I will think of the empty shelves and remember.