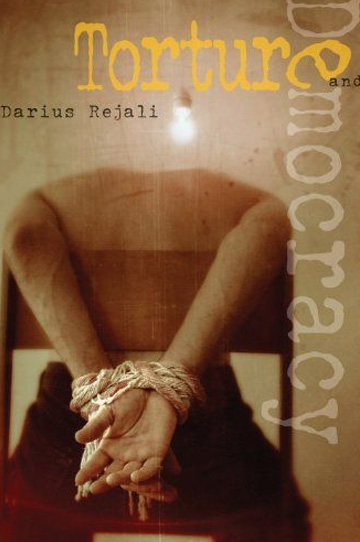

‘Torture and Democracy’ is Definitive

January 27, 2008 | San Francisco Chronicle

Democracies, not despots, created methods that ultimately don’t work.

A”dunk” in water, said Vice President Dick Cheney in October 2006, referring to waterboarding, is “a no-brainer for me” if it can save lives. The statement set off a media uproar and soon was hedged with Orwellian qualifiers and obfuscations: America doesn’t torture, full stop. But we use tough, “enhanced” interrogation techniques, and we won’t tell you what they are. Apparently, that means that waterboarding is not torture. Watch the trick in slow motion, but with a flashier example: (1) we saw off fingers; but (2) we do not torture; ergo (3) sawing off fingers isn’t torture.

But waterboarding is torture. The technique includes strapping a prisoner to a tilted board that elevates his feet and lowers his head and stuffing cloth into his mouth while water is poured over his (usually bagged) face. It is frequently, and inaccurately, described as creating a “sensation of drowning.” Nonsense: Waterboarding is forced drowning, interrupted, for the prisoner will die if the flow of water is not cut off in time. So in defending waterboarding, Cheney is saying that near-suffocation is not torture. Presumably, interrogators may also permissibly tie a plastic bag onto a prisoner’s head until his face turns blue. In our new paradigm, non-scarring brutality that doesn’t actually kill the prisoner is legitimate. Take a left, then another left and if you pass death, you’ve gone too far.

Like other tortures, waterboarding has a history, and oh how soon we forget. An American soldier was court-martialed in 1968 when the Washington Post ran a photo of him waterboarding a Vietnamese prisoner, and, in 1947, the United States prosecuted Japanese officer Yukio Asano for war crimes for the same behavior. Darius Rejali, a political scientist and noted expert on torture, explains that waterboarding is simply a variant of an old Dutch style of water choking. Dutch paymasters used it on British merchants in the East Indies as early as 1622, presumably as a sort of early kneecapping when the Brits didn’t meet sales figures. Waterboarding also appeared briefly in Algeria and Cyprus in the 1950s, and in Pol Pot’s Cambodia in the 1970s.

Rejali’s massive book, “Torture and Democracy,” is an exhaustive study of this and other “clean tortures,” or tortures that leave no permanent scars. Electrotorture, water tortures, stress and duress positions, beating, noise, drugs and forced exercises all make an appearance. The book is a towering achievement, a serious work of social science on an urgent topic that is too frequently surrounded by assumption and myth. It should be read and disseminated widely. Better hold Cheney’s copy, though – he’d probably mine the appendices for new ideas.

The book is devoted to exploding one myth in particular: that clean tortures can casually and reliably be traced to the ancients, or, failing that, to the Nazis. Rejali’s provocative thesis is that most clean tortures were actually born in democracies, especially imperial Britain and France. He persuasively argues that the rise of clean torture was a reaction to transparency and monitoring in democratic states: Torturers could carry on despite public scrutiny as long as they left no scars. Although Rejali does not discuss it, this thesis plays out daily in the American legal system. Immigration courts, for instance, handle thousands of asylum applications every year, and judges usually demand that alleged torture victims produce evidence of scarring or hospitalization. No scars means no torture, and the applicant is sent home.

To his great credit, Rejali repeatedly stresses that countries that use clean torture aren’t as awful or as culpable as traditional torturers of the eye-gouging and genital-poking variety. One suspects that most prisoners would rather be interrogated in the United States than in Syria or North Korea, where they would not only suffer but be maimed and usually killed as well. But clean torture is increasingly a problem in the developing world, too, because international human rights monitors now shine their lights into even the darkest corners.

One criticism is that Rejali pays insufficient attention to the possibility that democracies use clean tortures not to avoid detection but because the techniques are less barbaric than traditional tortures used in other countries. Forcing a sopping wet Guantanamo prisoner to do jumping jacks until he passes out in a freezing room next to blaring speakers sounds a lot like torture. But if we must quantify suffering, it’s not as bad as having one’s limbs hacked off one by one and the stumps fried with a blowtorch. For one thing, although all torture is psychologically devastating, clean torture does not create the added terror of permanent disfigurement.

But the justification of any torture assumes that it works even though it is nasty. Rejali ends the book with a devastating critique, showing that torture is actually worse than futile. Since it is done in secret, it is hard to analyze systematically, but Rejali debunks the anecdotal cases cited by torture apologists such as Alan Dershowitz, showing that claimed “ticking time bomb” victories are overblown, unsubstantiated or at best produced redundant information. Rejali also reminds us in vivid terms that prisoners will say anything under torture – Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi, for example, helped establish the since-discredited “connection” between al Qaeda and Saddam Hussein that was cited by President Bush, George Tenet and Colin Powell as grounds for invading Iraq.

This is an unhappy subject to tackle, and at 849 pages, “Torture and Democracy” can be a fearsome book. (“This chapter covers ways of striking other human beings with whips and sticks that leave few marks.”) Rejali ends it with a poignant admission of how much his research has taken out of him, saying that he retreated to “my scotch, my accordion, my friends, and my surfboard.” But if his work has been difficult, it has also been terribly important. May it not be in vain.