To Fame and Fortune

May 11, 2015 | The Barnes & Noble Review

As a young man, Saul Bellow radiated confidence about his future as a writer. Alfred Kazin observed that “he carried around with him a sense of his destiny,” as though he “expected the world to come to him.” Referring to Bellow’s uncanny gift for language, another friend told him, “You don’t dive for those pearls — they just come to you.” Bellow spoke of giants like Hemingway and Joyce not as infallible masters but as men with whom he shared a line of work. Yet notwithstanding destiny, it was work. Rain or shine, home or away, Bellow stuck to his routine, which revolved around an intensive writing session each morning. He would enter the study with a towel wrapped around his neck, like a weightlifter or a boxer, and emerge at lunchtime, towel drenched, author spent.

If Bellow’s eventual success required dedication to his craft, it also benefited from a certain prickly detachment. He participated in daily life — five wives, love affairs by the score, cities, spats, rejection, children — but at a slight remove, watching. His second wife described him as “like a bird, very bright, observant, like a magpie, going to take something and use it.” Aware of his own gifts and jealous of the limelight, the young Bellow was quick to perceive a snub. He paid the bills with university teaching and found East Coast English professors insufferably self-important. A child of Chicago, he delighted in puncturing egos. “My lack of humility was aggravated by the rejections I met or expected to meet,” he recalled. Spotting the eminent literary critic Lionel Trilling entering one party, Bellow called out, “Still peddling the same old horseshit, Lionel?”

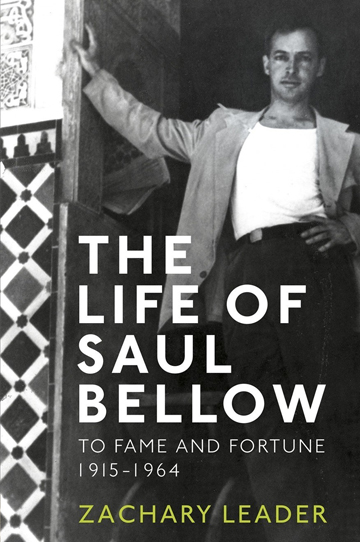

It is hard to imagine a more fascinating subject for study among American writers than Saul Bellow: brilliant, jazzy, touchy, “out of breath with impatience — and then a long inhalation of affection,” in his own words. The first volume of Zachary Leader’s highly anticipated biography, The Life of Saul Bellow: To Fame and Fortune, 1915–1964, has just arrived, and it is a revelation. To this point, the standard life was Bellow, by James Atlas — an astute and highly readable but damning account that seemed to take the other guy’s side at every turn. Atlas’s Bellow was “a master of self-exculpation” who “lacked the reserves of self-esteem needed to engage in rigorous self-criticism.” This portrait troubled Bellow’s many admirers but was ultimately too hostile to be convincing.

The Life of Saul Bellow is night-and-day positive. Leader, an English professor at Roehampton University who is known for his well-received biography of Kingsley Amis, is an unabashed fan of Bellow’s writing and a sympathetic chronicler. He gently but firmly takes issue with Atlas’s harsh judgments, suggesting that they are the result of friction between author and subject. Bellow’s actions do sometimes speak poorly for themselves, especially his carefree philandering, and Leader presents them for the reader to judge. When the question of motive arises, Leader’s reflex is generosity rather than snark.

Leader’s book is not without faults. His Chicago geography — an important qualification for a Bellow scholar — leaves something to be desired. Michigan City is east, not south, of Chicago, and Ravenswood is a neighborhood in the Windy City, not a suburb of it. More consequentially, Leader makes the questionable decision to describe the people in Bellow’s life with extended reference to their fictional counterparts. The character Simon in The Adventures of Augie March walked and talked a certain way, and therefore, Leader suggests, so did Bellow’s brother Maury, on whom Simon is based. The same goes for friends, colleagues, paramours, and rivals. Anyone who ever wondered whether they made an appearance in a Saul Bellow novel can find the answer in this exhaustive compendium. But as Leader knows, Bellow did not merely reproduce people wholesale; he shaped his view of them to his own fictional ends. Divining the point at which life ends and art begins is risky business; without precise delineation, it shortchanges both.

To Fame and Fortune is nevertheless a tremendous, authoritative book. This volume encompasses Bellow’s youth and young adulthood, covering the publication of his three most beloved novels: Augie March (1953), Henderson the Rain King (1959), and Herzog (1964) — the book that made him famous on a national and international scale. Herzog in particular goes some way toward ratifying Leader’s method, for Bellow based it on the breakup of his second marriage, after his wife Sasha had an affair with his friend and colleague Jack Ludwig. Leader starts the following section in an amusing deadpan: “Now began a period of strenuous womanizing.” When Bellow sent Sasha her effects and personal belongings, he included a few barrels of garbage and ashes, topped with a pair of Ludwig’s shoes. The man could be petty.

But he also overflowed with humanity. Leader is at his best when delighting in Bellow’s prose, to which he repeatedly returns. “Bellow was a famed noticer and his novels and stories are packed with things perfectly seen,” he writes. These include the art critic with eyebrows “like caterpillars from the Tree of Knowledge”; the rabbis with “beards that were thick and rich, full of religion”; and the harried Henderson, rushing through Grand Central Station “so that my shoes and pants could scarcely keep up with me.” Leader has it right when he describes the thrill of pleasure one feels when reading such lines, so closely observed and so precisely rendered. It is the feeling of recognition rather than discovery: Bellow’s gift to letters is “more mirror than lamp.”

The Life of Saul Bellow is long and hugely detailed. It encompasses all, from events of great consequence right down to the latest fad. In the former column was Bellow’s lifelong search for approval from his father, Abraham, who died before Bellow became a literary celebrity. A relative described the way Abraham “loved talking for hours about Saul’s foolish choice of working for such a small salary when he could have joined him in the coal business.” Yet at Abraham’s funeral, Bellow wept until his brother Maury told him to stop carrying on like an immigrant. As for fads, Bellow tried out Reichian therapy, which focused on the centrality of the orgasm. The exercises were silly pseudoscience, but in one respect at least, they fit their man. Overwhelmed by life’s beauty and variety and ridiculous impossibility, Bellow would head off into the wilderness, cast his face to the sky, and roar.