Of all the artifacts that persist in the face of new technology, the globe may be strangest. Books have stubbornly clung to market share despite the rise of e-readers. Mechanical wristwatches remain the subject of fascination even in the age of smart devices. Yet those analog objects retain a practicality that their digital counterparts sometimes lack: A page is easier on the eyes than a screen, for instance. Globes have long since lost any vestige of utility. When a smartphone’s GPS can zoom in to street level in an instant, what point is there in consulting a large, bulky sphere? Yet finding where you’re going and knowing where you are can be two different things. In an era of fragmentation, it is bracing to see a thing whole.

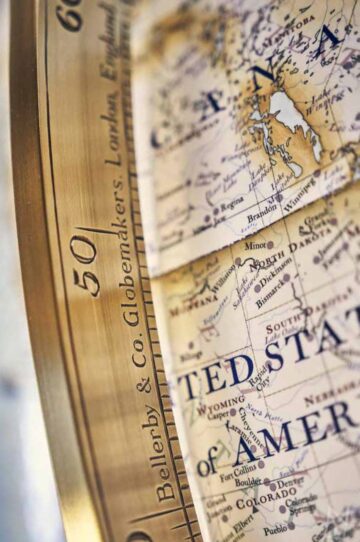

In his book about their makers, Peter Bellerby describes globes as “beguiling objects full of detail, color, and wonder.” They offer the childlike joy of experiencing a miniature in all its rich variety and texture. Mr. Bellerby’s London boutique makes globes by hand, the largest with a diameter of more than four feet and costing about $90,000. There is a long waiting period to buy one of the 600 pieces the firm produces annually, yet business is strong. Bellerby & Co. credits a good product: not just the globes—although they are remarkable works of craftsmanship—but the Earth. Globes remind us, Mr. Bellerby writes, that we live on “a beautiful planet floating in space, spinning within an infinite universe and an evolution of time so long that it is difficult to comprehend.”

The Globemakers: The Curious Story of an Ancient Craft presents an esoteric history of globes, a detailed description of how the author builds them, and an account of his company’s development. The most arresting feature of the book is its appearance, for which the publisher, Bloomsbury, and book designer Dave Brown deserve particular notice. The Globemakers is a lovely object, beautifully conceived and skillfully executed. With its digressive text boxes, sketches and photographs, it encourages the reader to linger and explore. In that sense the rectangular book echoes the round object it chronicles.

The very first globes are thought to predate Christ, but the oldest surviving globe was made between 1492 and 1494 by Martin Behaim in Nuremberg, Germany. (Notably, the first known watch was made in the same city around the same time.) This globe—called the Erdapfel, meaning “Earth apple”—is almost 8 inches in diameter; it was made of linen strips pasted onto a clay ball and then painted with a map reflecting the travels of Marco Polo. The Americas do not appear and Japan is enormous. Featured throughout are “over one hundred miniature objects and figures—flags, saints, kings on their thrones, elephants, camels, parrots and fish, and fantastic creatures including a sea serpent and a mermaid.” Such esoterica continue to embellish globes to this day, tickling the imagination and combating monotony, particularly in the vast blue reaches of the Pacific Ocean.

In the age of exploration between the 15th and 17th centuries, globes helped seafarers plot courses and fix trade routes. During subsequent centuries they threatened to become obsolete in light of technological developments such as sextants and marine chronometers. “A new breed of astronomers and navigators maintained that globes might well be useful to record new discoveries, but not to make them,” Mr. Bellerby writes. Cartographers placed invented towns on their maps to snare plagiarists who tried to steal their work. Boston emerged as the home of American globemaking, later to fall to the lithographic printing center of Chicago in the mid-19th century. Globes became widely available educational tools, standardized and accurate—but unlovely.

Mr. Bellerby took an interest in globes in 2008 after trying, and failing, to buy one for his father for a landmark birthday. He found that the market offered either cheap, mass-produced pieces or outrageously expensive antiques: neither appealed. So he took advantage of the great recession and set out to make one himself, learning by trial and error and building a company as he went along. (He delivered the birthday gift a couple years late, in 2010.) The later business journey, which he recounts, is interesting enough but less engrossing than the historical tidbits or the chapters on how a globe is made.

After crafting a perfect sphere, which is no mean feat—ask Leonardo da Vinci—a globemaker must cover it with gores. These, Mr. Bellerby explains, are surfboard-shaped map sections that can be printed and laid flat and then are affixed to the sphere with the pointed tips resting at the north and south poles and the widest portions covering the equator. Cutting the gores with a scalpel, stretching them, gluing them, and laying them with exquisite precision, is the heart of the globemaker’s craft. Mr. Bellerby estimates that learning to cut gores correctly takes 50,000 practice attempts. Once these are affixed, the globe must be hand-painted and dried and then mounted onto a bespoke base. The finish on a Bellerby globe has the shiny brilliance of hard candy.

The maps that appear beneath this lacquer are political minefields. Does Taiwan belong to China or is it a sovereign state? Where does India end and Pakistan begin? What precisely are the contours of the nation of Israel? It all depends who you ask, and the answer may one day change. “A globe is and has always been a record of a moment in history,” Mr. Bellerby writes, “which can only ever be fully accurate at the instant we print the map.” He notes that there is no international standard of cartography, and his firm must not risk committing a crime by shipping an offending globe to a country touchy about such things. The unsatisfying solution is occasionally to edit maps based on the globe’s destination. “We mark disputed borders as disputed. We cannot change or rewrite history.”

Globes are like other anachronisms that reflect the way things were: solid, durable, based on a knowable past instead of an uncertain future. A beautiful globe in a handsome library is the essence of romance. In this sense, it is right that a book should be the medium to commemorate Bellerby & Co’s unlikely success. Yet artisanship of this type does something else: It rewards a desire for tactile engagement in a digital era, when so much daily ephemera comes and goes with our hands never touching it. Mr. Bellerby captures this basic human impulse by reporting a request that many visitors to his studio make. After admiring a globe and then tentatively stepping closer, they often ask—to his delight—“May I spin it?”