There was a real fear among White House eggheads that President Richard Nixon would get sloshed and ruin his ceremonial toast during a banquet at China’s Great Hall of the People in 1972. One of his assistants discovered on an advance trip that the Chinese liquor mao-tai was potent stuff; he warned in a memorandum that “under no repeat no circumstances should the president actually drink from his glass in response to banquet toasts.” In the event, Nixon performed beautifully. And that wasn’t the evening’s only victory. Compulsory chopstick practice among the American delegation averted unsightly blunders. And Pat Nixon’s hopes for the China trip were realized: She was offered a pair of pandas and screamed with delight. The American press corps, football fields away in the gigantic hall, stood on their chairs and watched the spectacle through binoculars.

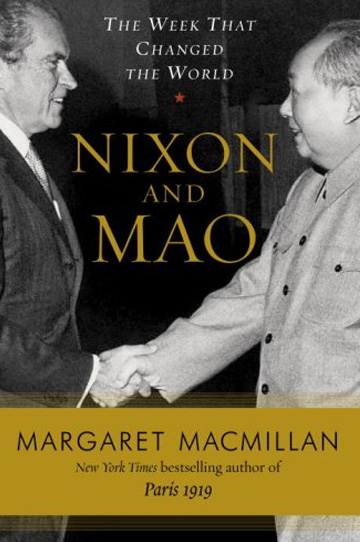

Yes, diplomacy is silly. But as Margaret MacMillan writes in her splendid new book, “Nixon and Mao,” “[t]he banquet, like Nixon’s trip itself, was about symbols, about handshakes and the exchange of toasts between leaders whose countries had for decades treated each other with suspicion.” Suspicion is a euphemism: The United States and China had had no diplomatic relations since 1949. They had already fought one proxy war against each other in Korea, and were in the middle of their second, in Vietnam.

But as the 1960s gave way to the ’70s, Nixon realized China could be a useful ally against the Soviet Union and could help the Americans bring their boys home from Southeast Asia. A thaw made sense to the Chinese as well; relations with their Communist patrons in the U.S.S.R. had grown increasingly bitter and confused as the Soviets watched China shred itself in an orgy of iconoclasm, brutality and all-around madness called the Cultural Revolution. China and the Soviet Union nearly went to war in 1969 over a border dispute.

The story of tentative diplomatic overtures that followed is colorful and dramatic. The U.S. ambassador to Poland made a point of casually bumping into his Chinese counterpart after a fashion show in Warsaw, carrying a message that his government was interested in chatting informally. Pakistan, a mutual ally, facilitated preliminary talks, which were followed by “pingpong diplomacy” in 1971 — an invitation, devised by Mao himself, to the American table-tennis team to come to China for a tournament. A long-haired American player broke the ice by asking Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai what he thought of hippies.

Shortly thereafter, Nixon decided it was time to go personally to China for direct talks with Mao, and sent Henry Kissinger, his national security adviser and chief negotiator, to get everything ready. Kissinger, who comes across here (as he has before) as amoral, duplicitous, insufferably self-important and childish, insisted on complete control over the China initiative, refusing even to allow the secretary of state to appear in photographs taken during the trip. He traveled to Pakistan and devised a ruse about being sick; while the hacks from State thought he was convalescing in the mountains, he put on a disguise and flew to China. He and Nixon characteristically kept everything top secret, telling themselves that if word got out, American popular opinion would scupper the visit. Their real motive appears to have been protecting Nixon from the anti-communists in his party’s right wing in the 1972 presidential election.

Little of substance happened during the trip. There were the obligatory sightseeing outings, photo ops and state dinners. Nixon and Mao met once, briefly, but by that time Mao was fat and sick, and spent most of his time surrounded by a coterie of concubines-cum-minders. Zhou, a shrewd and urbane statesman, was the real point man for China. The trip culminated in a painstakingly negotiated joint communique in which the Americans toned down their military support for the government in exile in Taiwan and the Chinese feinted toward pushing the North Vietnamese into peace talks. The document was as bourgeois as they come: Zhou was persuaded to replace an exhortation for world revolution with a call for “important changes and great upheavals.”

MacMillan’s subtitle is “the week that changed the world,” but did any of this really matter? Perhaps the trip averted further violence between the two countries, and yes, it established a framework for relations. But what has that framework produced? Thirty-five years later, anti-American invective still colors the pages of the People’s Daily. The United States still backs Taiwan — if not as the rightful seat of Chinese government, then as a fledgling democracy. Economic competition between the two countries is full of hot nationalist rhetoric; there is even talk of a new cold war. But at least while Americans and Chinese enjoy a nice radioactive sunbath after World War III, they’ll still have Nixon in China.