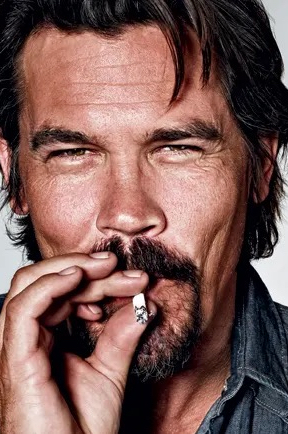

Josh Brolin is a postmodern cowboy. Masculine but too vulnerable to be macho, at ease on a motorcycle or on horseback, he looks best with dust in the grooves of his skin. Some of his scars are self-inflicted. “I have made life harder than it’s needed to be,” the actor concedes in his memoir, From Under the Truck, before cataloguing his “greying beard, ruined shoulder and ‘testicular problem.’” Mr. Brolin’s coin of the realm is a face that has a grin on one side and a scowl on the other. The former lets him portray a certain type of aging scoundrel in films such as Sicario (2015); the latter produces tough stoics. In Dune (2021), when admonished to smile for visiting dignitaries, his character growls, “I am smiling.” Yet Mr. Brolin was probably the first cast member to start laughing after the director yelled cut.

From Under the Truck is raw, honest and self-effacing. It gives snapshots of a life filled with highs and some staggering lows, including lies told, drunken rants, trips to jail and at least one knife to the gut. Composed by Mr. Brolin himself rather than ghostwritten, the narrative is presented in nonlinear, diarylike prose and occasional verse. If a celebrity memoir can be typecast by its author’s preoccupations—status, vanity, political moralizing, petty scorekeeping—this is a book about parents and children. Its best passages recall Mr. Brolin’s mother, Jane Cameron Agee, who “was armored with a character so unique and memorable that to die would be an insult to her mythology.”

Mr. Brolin’s early years were spent in Paso Robles, Calif., and he writes vividly about his childhood. “As a kid I woke up before first light and fed at least forty horses.” On Saturdays, the tradition was to eat a huge breakfast at Hoover’s Beef Palace, where cowboy hats “were customary and worn without affectation.” Mr. Brolin adapted to the coastal lifestyle after moving to Santa Barbara at age 11. He and his friends called themselves the Cito Rats and spent their days surfing, taking LSD and getting arrested. “We’d learned what punk rock was before we could put a name to it.”

The constant—or inconstant—through the years was Mr. Brolin’s peripatetic mother. He calls her the most important person in his life, and she brings out his best writing. “My mother was five feet three inches tall, at best. She weighed a measly 105 pounds and she drank Calypso Coffees by the dozen,” he writes, describing her favorite spiked beverage. “Rhinestoned and leather fringed,” she had a “three-hundred-pound voice,” slept with a pistol next to her bed, was once committed to a state mental hospital and seduced many a man. “She’d make herself known. She couldn’t help herself.” Yet for the young Josh, Jane represented stability. His father, the actor James Brolin, was rarely around. Jane died after a car crash in 1995.

When it comes to the movies, the younger Brolin seems less interested in slick entertainments than the friendships and adventures that his line of work affords. After early success as a child actor, he disappeared into the Hollywood wilderness for decades. “I was a loser,” he bluntly admits. “I was someone who had never hit but was supposed to have. I’d had The Goonies but that was long over and I had done nothing of note since. I was past the point of rediscovery.” Then came his starring role in the celebrated 2007 western No Country for Old Men, directed by Joel and Ethan Coen. Star struck to be near Tommy Lee Jones and suffering from a broken collarbone, Mr. Brolin nevertheless recognized his chance. “Something’s trying to keep me down,” he writes of the charged moment. “I won’t let it.” The performance relaunched his career. Steady work has followed with the finest directors in the business, including Ridley Scott, Denis Villeneuve and Paul Thomas Anderson.

Parenthood is the source of the author’s greatest joys and fears. Stories about small moments with his four children fill the pages. “Sleeping with an infant next to you, I’ve learned, is not sleeping. It’s resting your eyes.” Mr. Brolin catalogs all the terrifying points to keep straight—“sleep on the back, now on the side; don’t run on wood floors with socks; we can pretend things are knives but we don’t actually pick up knives; pull over when you forget to buckle them into their car seats”—and recounts a heart-stopping night when he thought his adult son had died in an accident. He concludes that the arrival of children was “like a divine intervention that slapped the ego out of my self-absorbed youth.”

With his own father hovering just outside the frame, Mr. Brolin found a friend and father figure in Cormac McCarthy—the novelist who wrote No Country for Old Men, the basis of the film. Naturally, the two talked about their children, and the actor was with the author the night before McCarthy died. Mr. Brolin—who, like his mother, often seems to go one step too far with people—lacerates himself for once asking McCarthy to sign his typewriter. It was an insult to their friendship, he realizes. What Mr. Brolin valued was not proximity to literary brilliance but a wise friend who was “simple, straightforward, and uninterested in nonsense.” That is also a good description of this remarkable book.