President versus chief justice: it’s a compelling narrative. Everyone knows the power of the president, with his launch codes, legislative veto, and ability to get network air time whenever he wants it. The Supreme Court, though, wields a bazooka of its own: the power of judicial review, which allows the Court to invalidate laws that violate the Constitution. The chief justice leads the Court, and the cleverest chiefs have outfoxed presidents. John Marshall frequently clashed with Thomas Jefferson, in the process establishing judicial review and securing the Court’s stature as a co-equal branch of government. More recently, Charles Evans Hughes outmaneuvered Franklin Roosevelt by writing a single letter that soured Congress on Roosevelt’s plan to pack the Court with liberals. Presidents underestimate chiefs at their peril.

Both Jefferson and Roosevelt faced chief justices who belonged to the opposing political party. But in conflicts between the executive and the judiciary, matters are not as simple as two partisan infantries marching straight at each other across an open field. At times, the president and the Supreme Court more closely resemble Cold War nemeses, all subterfuge and mind games beneath a veneer of diplomatic courtesy. When the current chief justice, John Roberts, fumbled the oath at Barack Obama’s inauguration in 2009, White House lawyers arranged a private do-over, just to be safe. Obama was a little testy about the hiccup, and Roberts must have been mortified. Yet such is the confidence and pride of the current, brilliant chief justice that he again performed the oath from memory, refusing cue cards. He and Obama smiled politely, like a pair of premiers over tea. Then they ordered their fleets into hostile waters.

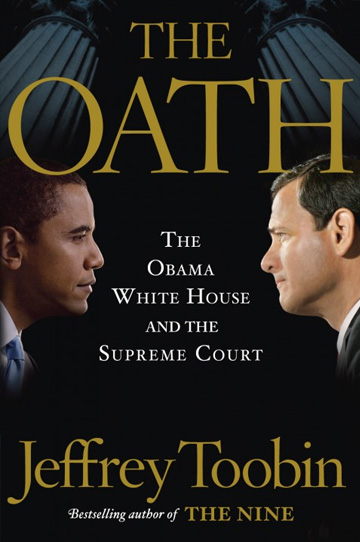

In The Oath: The Obama White House and the Supreme Court, Jeffrey Toobin chronicles the tense relationship between Obama and Roberts. Toobin is the legal affairs correspondent for The New Yorker and a reliably keen observer of the Court. Many of the book’s pages range beyond the Obama-Roberts dynamic to cover recent developments on the Court generally — and do so well, with wit and many revealing details. But a few memorable encounters between Obama and Roberts serve as the spine of the story, which is structured as a play in three acts.

Act One is the kerfuffle over the presidential oath, which was an unusual stumble for Roberts, a man universally admired during his years in private practice for his flawless delivery at the world’s most stressful podium — the one facing the justices. The incident established an atmosphere of awkwardness and antagonism between the two men. The second act finds the stakes raised: In January 2010 the Court struck down key provisions of the McCain-Feingold campaign finance law, with a bare majority of conservative justices concluding that it violated the First Amendment rights of corporations, unions, and other business organizations. Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission is the Court’s most derided decision since Bush v. Gore, for its upending of decades of precedent, its stubborn disregard of common sense (Corporations are people? American elections need more money?), and its embodiment of the judge as partisan rather than umpire. The decision has caused major damage to the Court’s reputation.

Six days after the Court decided Citizens United, Obama criticized it in his State of the Union address. Toobin reveals that, remarkably, Obama’s speechwriters did not consider the effect this would have on the six justices sitting in the audience, leading Obama to ad-lib the softening line, “with all due deference to separation of powers.” It was Samuel Alito, not Roberts, who mouthed “not true” to Obama’s claim that Citizens United could allow foreign corporations to exert influence over American elections. But Roberts was sitting in the audience too. He mused in a speech several weeks later that it is uncomfortable for a justice to have to sit through a “political pep rally.” That is a fair point. On the other hand, the more overtly politicized the justices become — by voting along ideological lines and using fresh majorities to overturn disfavored precedents — the less room they have to complain when their political opponents call them out.

Citizens United sparked a backlash against the Court, and without this response Roberts might have reached a different result in the health care case in June 2012. Toobin’s third act complicates the view of Roberts as nothing more than Obama’s wily antagonist. Faced with the prospect of five Republican appointees invalidating the centerpiece of a Democratic president’s domestic program in the middle of a presidential election season, Roberts cast a shocking fifth vote to uphold the heart of the Affordable Care Act, infuriating conservatives and damaging his bona fides as a movement man. He then announced his intention to vacation on Malta. “Malta, as you know, is an impregnable island fortress,” he quipped.

It is too soon for Toobin to provide much color to the maneuverings that produced this extraordinary outcome. He does note that Roberts furiously lobbied Anthony Kennedy, in vain, to join him for a 6-3 decision rather than a 5-4 one. But where the details are scant here, Toobin supplies them in abundance elsewhere, demonstrating a particular talent for nailing each justice. Roberts, he notes, is the Court’s best writer and Alito asks the toughest questions at oral argument. John Paul Stevens, who retired in 2010 at age 90, is “a remarkable physical specimen,” and Anthony Kennedy, the Court’s swing voter, is “not a moderate but an extremist — of varied enthusiasms.” The Court’s newest member, Elena Kagan, took pains to insulate herself from the health care case while serving as solicitor general, so that she could participate should Obama nominate her to the Court. Stephen Breyer is “not a linear thinker,” and “sometimes found himself caught up in his own curlicues of erudition.” Antonin Scalia has officially descended “from conservative intellectual to right-wing crank.”

Two things seem clear about Roberts’s vote in the Obamacare case and the direction that decision portends for the Supreme Court. The first is that Roberts put the needs of the Court above his own preferences. The second is that he has bought himself some breathing room: the glare has shifted from the Court back to the presidential slugfest and partisan gridlock on Capitol Hill. In other words, Roberts is an honorable man and commendable leader who nevertheless knows the value of a tactical retreat. Next term the Court considers such hot-button topics as the Voting Rights Act and the Defense of Marriage Act, and Roberts will be free to address both cases without another Citizens United hanging around his neck. As both Roberts and Obama know, presidents come and go, but chief justices can afford to play the long game.