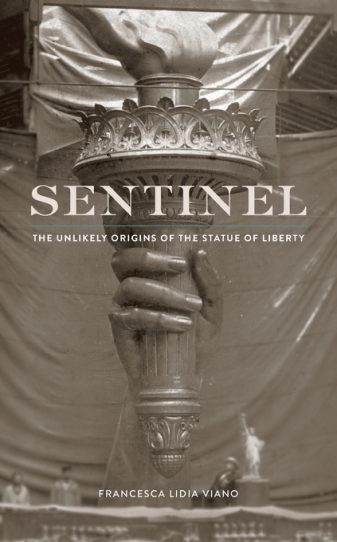

Look into her face and you might be surprised: Lady Liberty is cold and hard. She has a strong jaw and a long, geometric nose, broad at the top and straight all the way down. Her lips above a square chin are full but unsmiling—frowning, almost scowling, and bearing perhaps a hint of menace. A certain eyelessness unsettles her expression further, aligning her with Roman works of antiquity and attaching indifference to her timeless gaze. She does not look like a benevolent shepherd embracing the huddled masses as they arrive in the New World, although that is what she has come to represent. To judge by her expression, she could as easily be holding a sword and shield as a torch and tablet. Does she offer welcome—or warning? Who is she and why is she here?

For an instantly recognizable national monument that has adorned the postage and the currency, the answers should be obvious. Yet put the question differently and even more uncertainty enters the frame, as Francesca Lidia Viano shows in “Sentinel: The Unlikely Origins of the Statue of Liberty.” Why in the world does a “colossal, anthropomorphic lighthouse” sit in New York Harbor wearing a scowl and the color green? Add a dash of contemporary politics and matters become cloudier still. Perhaps the Statue of Liberty does not mean the same thing in an era of nationalism and closing borders that it meant in 1884, when the statue was officially unveiled.

In her fascinating, digressive and relentlessly inquisitive study, Ms. Viano, an Italian historian, demonstrates that the statue is mysterious and full of surprises. She traces the statue’s origins and history, unraveling the distinct strands of its meaning but resisting the urge to write it off as a cipher open to all interpretations. “Born in the East and later used to symbolize the West, made by the French to portray and simultaneously warn America—not to mention threaten Britain and Germany—and ultimately used by America to glorify and justify their world hegemony, the Statue of Liberty is a global icon, not an empty one.”

The book’s protagonist is the statue’s French sculptor, Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi. His commission to build a monument to the complicated friendship between America and France came about through a combination of ambition, opportunism, nationalist resentment and huckster hustle. He lived and dreamed in an age of massive public works. The late 19th century was the era of the Suez and Panama canals, and the vast scale of those mighty projects shaped his vision for what he came to call Liberty Enlightening the World.

Bartholdi originally intended some version of the statue to be placed in Egypt. He visited that country in 1855 and marveled at the titanic scale of the ancient temples, as well as the strength and dignity of the country’s laboring peasant women, known as fellaheen. Smitten by orientalism, he began sculpting fellah maquettes, which today look like distant ancestors of the Statue of Liberty. Bartholdi thought that such a statue could stand at the crossroads of the Suez Canal, but he could not secure the pasha’s blessing. His dreams of a project in Egypt ended in 1869, and he returned to France.

The Franco-Prussian War and the subsequent violence of the Paris Commune drove him away again in 1871—this time to America. He left seething over Germany’s theft of Alsace and Lorraine. Like his countryman Alexis de Tocqueville, Bartholdi traveled the vast American landscape, beheld its wonders and left a changed man. As he toured the cities of the East and the mountains of the West, he began to envision a new home for his fellah statue. Had it been erected in Egypt, it would have symbolized French progress to the east. “If placed in America,” Ms. Viano writes, it would become “the herald of French civilization and economic expansion to the new world.”

During his journey, Bartholdi made powerful allies. He enjoyed an audience with President Ulysses S. Grant and formed a friendship with the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He also corresponded with the man who would become the statue’s intellectual patron: Édouard de Laboulaye. An abolitionist and admirer of America’s Constitution, Laboulaye pursued domestic politics in France while encouraging Bartholdi to place the statue in the United States. Bartholdi, however, stood out as a hopeless European, his English broken, his fashions all wrong and his bathing suit “too skimpy for prudish local tastes.”

Then fate intervened. With the centenary of American independence approaching in 1876, a French club in New York called the Cercle de l’Harmonie sought to finance some sort of commemorative monument. France after all had fought alongside the United States during the Revolutionary War before experiencing its own iconic revolution. And, as Laboulaye pointed out, there were commercial interests to consider. “Our cities, our societies, our industrial establishments, our big commercial houses” would all benefit from the appreciation that such a gift would engender. Bartholdi spotted his chance and excitedly pledged to build “a lighthouse of independence” as a gift from France to America. If only he could fund it.

Backers hastily formed a group called the Franco-American Union, which began accepting donations. Newspapers ran a public appeal. But after the centennial came and went in 1876, Bartholdi needed a new gimmick to attract financial support. He found it in a venture that would prefigure thousands of kitschy trinkets and key chains: He would sell miniature statues. A last-minute effort by the newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer helped secure funding for the statue’s enormous pedestal. Meanwhile, American cities competed to become the home of the statue, with Boston, Washington and San Francisco under consideration and Philadelphia vying against New York for the final honors.

French workers assembled the colossus from lumber, plaster, iron and copper. It was shipped to the United States and unveiled in 1884, to much consternation. Why a statue commemorating American independence rather than the much more recent Civil War? Why a paean to French-American relations in the middle of a serious trade dispute between the two countries? Bartholdi’s and Laboulaye’s Continental sensibilities only added to the confusion, for they saw the statue as a symbol of enduring French colonial power against the hated Germans and France’s old rival, Great Britain. As Ms. Viano writes, “the statue’s promise of regeneration included the promise of its enemy’s ruin.”

Here her book is at its most provocative, and most fascinating, as she explores the statue’s “warlike essence.” It was made from copper, the same metal that produced cannons, and sat on an island with a military fort that would later be administered by the War Department. To signal ‘V’ for victory in Europe in 1944, the statue’s torch blinked “dot-dot-dot-dash,” like some silent beacon of the home guard. Above all, Lady Liberty looks more like a praetorian than “the benign mother of exiles.” Ms. Viano goes too far in describing the monument as a kind of Trojan Horse gift to the Americans, full of French colonial perfume, but the thrust of her argument rings true: Lady Liberty is fiercer and far more complex than we ever knew.