Sunday dinners at Joe Alsop’s Georgetown home followed a strict protocol. The evening began with dry martinis to disinhibit the guests: ambassadors, justices, reporters, and members of Congress. Ladies had to be escorted into the dining room, and the sexes disbanded after dessert: men to the library and women upstairs. (Alsop, a syndicated columnist for the Saturday Evening Post, favored the prewar ways well into the 1960s.) Conversation was expected to be lively and even contentious, though not partisan. The next day, after reading in Alsop’s column a juicy remark or two made at dinner, guests must drop off a calling card. This was a form of thank-you — for the evening, not necessarily for the food. Terrapin (turtle) soup was the host’s specialty. “Although its aroma reminded one a bit of the way feet sometimes smell,” Alsop recalled, “it was absolutely delicious.”

“In other cities, people go to parties primarily to have fun,” said Washington Post chairman Phil Graham during a grandiose and self-congratulatory toast at his own table in the late 1940s. “In Georgetown, people who have fun at parties probably aren’t getting much work done. That’s because parties in Georgetown aren’t really parties in the true sense of the word. They’re business after hours, a form of government by invitation.” Sometimes business had to be interrupted. Graham’s wife Katherine had a habit of knocking over the tea service if a fistfight seemed imminent. Alsop’s toucan once spat a half-eaten banana onto Defense Secretary Robert McNamara’s head.

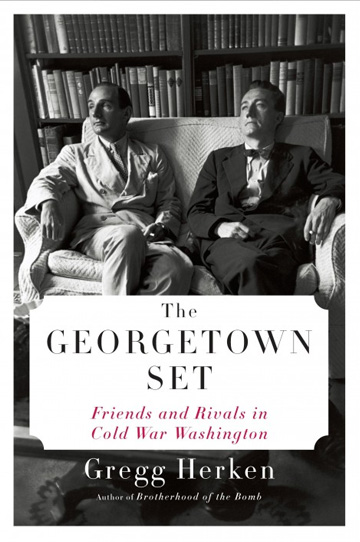

Gregg Herken makes these dinners a centerpiece of The Georgetown Set: Friends and Rivals in Cold War Washington, a lively and entertaining romp through the years of the Korean War, McCarthyism, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and Vietnam. In addition to the Grahams and the Alsops (Joe shared his column with his brother Stewart), the cast includes Soviet strategist George F. Kennan, CIA man Frank Wisner, diplomat Chip Bohlen, military analyst Paul Nitze, and of course Senator and Mrs. John F. Kennedy. During the months after his inauguration as president, Kennedy used to drop by unannounced at Alsop’s house, which became his “unofficial retreat and refuge,” in Herken’s words.

Characters abound, but Alsop is Herken’s principal subject. The book is very nearly his biography. Alsop was a catty busybody, a moralist, a neoconservative, and a dandy. Appearances and snubs mattered to him, and his life amounted to a series of snobbish embraces of all the touchstones of elite privilege. Resplendent in a kimono, he spoke in what they called Groton lockjaw: “an upper-class blend of Connecticut Yankee and Harvard Yard.” Alsop tried a little too hard to look the part while reporting from Minnesota farm country during the 1952 presidential election. “Sporting a green tweed jacket, tailored gray slacks, and highly polished, handmade shoes, Joe would nudge the interview subject with his walking stick and inquire, ‘So, what do you make of it, old boy? Eh?’ ”

A book like this, filled with glamour and personality, threatens to become frivolous. To Herken’s credit, The Georgetown Set usually chooses substance over form. One of his main points is that between the columns, ladder climbing, and sniping, Alsop managed to be wrong about most of the major issues of the century. A Cold War hawk, he favored escalation and confrontation with the Soviet Union at every turn. He aggressively promoted the war in Vietnam. A late convert to Richard Nixon’s camp, Alsop refused to report on Watergate. The sensitive and brilliant Kennan wrote to Alsop, “It is hard for me to discuss Vietnam with you, because you are — as you must well know — overbearing in argument in a manner that belies your own inner nature.”

Like his contemporaries, Alsop wrote forcefully about the sacred role of the press in a democracy, but he never missed a chance to cozy up to power. He gave President Kennedy copies of his articles to proof before they were published and stayed as the U.S. ambassador’s personal guest when he visited Vietnam. What he prized more than anything was access, and he tried to ingratiate himself with every new president except Jimmy Carter, whom he loathed. Herken’s most valuable contribution is to portray Alsop as a case study in “the pitfalls to be encountered in the so-called access or elite form of journalism.”

The Georgetown salons began to disappear in the 1970s, partly in response to the rise of a new breed of hack: the investigative reporter. Beholden to no one, these journalists valued independence rather than connections and reported facts instead of gossip. Alsop despised them. After Seymour Hersch wrote about the massacre at My Lai in 1969, Alsop cornered him at a cocktail party and declared, “You, sir, are a traitor!” Thankfully, the rest of the Georgetown set did not agree; Katherine Graham’s Washington Post, after all, broke the Watergate story. With Alsop’s death in 1989 the salons finally ended, and that is for the best. Graham herself sounded their death knell, when she refused in the late 1960s to be sent away so the men could drink brandy and smoke cigars. Nothing like a party to change the world.