The Foie Gras Wars

April 30, 2009 | The Barnes & Noble Review

If a single dish could be said to embody the very pinnacle of man’s decadence, vanity, and moral ruin, it would be Pâté de foie gras de Strasbourg. This French specialty is made of a whole goose liver — unnaturally fattened to many times its normal size through force-feedings — wrapped in veal, the tender meat of a baby cow. A 19th-century restaurant critic describing a dining party’s slavering anticipation of a “Gibraltar rock” of the stuff noted that “conversation ceased, for hearts were full to overflowing,” while “imprinted on every face the glow of desire, the ecstasy of enjoyment, and the perfect calm of utter bliss.” Times may change, but you’ll still see that facial expression: it belongs to the baseball fan who catches a foul ball by shoving aside a child’s waiting mitt, and to the casino manager who anticipates the day’s take as a busload of working men arrive with their week’s wages. It is a look so smothered in glorious self-regard that it takes a moment to realize what it really means: not just, I care about me, but also, I do not care about you.

You can still find the dish, too — in Philadelphia, where the London Grill restaurant has substituted calf meat with calf liver for an all-viscera experience. But how to defend such extravagance when the obnoxious animal rights crusaders arrive? “God made ducks to have that liver — and He made it incredibly delicious!” reasons French restaurateur Ariane Daguin. “Why would it exist if not for us to enjoy it?” Put aside the blasphemous invocation of the almighty while appealing to sensual pleasure to justify brutalizing a defenseless animal. To answer Daguin’s question, the liver exists to emulsify lipids, store glycogen, and generally to facilitate its owner’s digestion. Ducks and geese find theirs indispensable, which is why toward the end of the weeks-long gavage — or force-feeding period in which great volumes of corn slurry are poured into their stomachs via a long tube inserted into their esophagi — the animals begin dying from liver failure. They also have difficulty standing and walking, and their enormous livers crowd up against their lungs, causing heavy panting. Once liver failure is nearly complete, the animal is sent not to the veterinarian but to the abattoir. What would be the point of a vet?

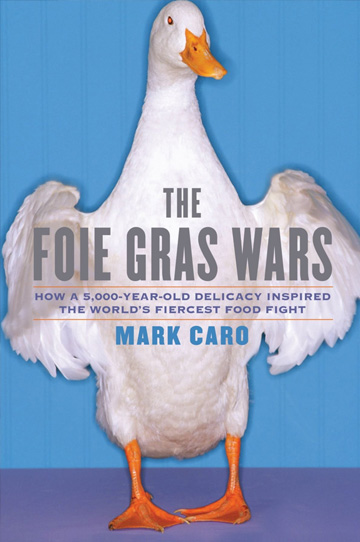

Mark Caro’s The Foie Gras Wars chronicles the many battles waged lately over fattened duck and goose liver. On the one side there are lots of variations on Daguin’s pleasure theme, as well as nakedly preposterous contentions by foie gras industry figures that swelling up the animals’ livers to ten times their natural size is only moderately “stressful.” On the other are indefatigable animal welfare advocates, who are reviled by the industry types but are increasingly sophisticated, mainstream, and effective. We also get to learn about technical innovations in preparing the delicacy: for several hundred years now, foie gras producers have employed such gentle means that they no longer have to nail down the geese’s feet or dash out their eyes.

There are interesting and serious issues to explore in the foie gras controversy, but where Caro’s book should analyze, it sensationalizes: he looks not for sober discourse but for loud fights, like the one between the London Grill and an aggressive protest group. His tone is strident, populist, sarcastic, and offensive, as when he coins crass nicknames for horrific undercover abuse videos, like “Rat Munching on Ducks’ Bloody Ass Wounds.” Even after seeing mistreatment on film and in person, Caro never hesitates to enjoy the perks of his research project; on being offered the umpteenth serving of foie gras, the hungry author “wasn’t going to say no.” And when leaving for a tour of French foie gras farms that would include dozens of opulent gourmet meals, he writes, “I realized that I was going to be in France for almost exactly the same amount of time that a duck is force-fed. I was experiencing my own personal gavage, albeit of my own free will and without a tube.” Such tone-deaf statements — the book is filled with them — crisply distinguish The Foie Gras Wars from Eric Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation, a book that Caro consciously seeks to emulate. Schlosser showed some fucking humility when writing about the suffering of animals.

Caro visited several American and French foie gras farms (his requests to tour others were rejected), and although he clearly strives to be evenhanded and honest in his reporting, the reader quickly begins to question his judgment. For instance, one of the book’s insights is that the animals used to make foie gras may not be much worse off than other factory-farmed animals, like layer hens or gestation-crate pigs. The point may be valid, but defending foie gras by saying it is only as bad as other types of intensive animal production is a little like defending cheating by saying it’s no worse than stealing. Factory farm animals live abysmal lives, so the contention that foie gras birds get similar treatment is an indictment of foie gras, not a seal of approval. Instead of making this obvious rebuttal, Caro provides easy cover to the chefs and restaurateurs who hide behind the specious argument that cruelty is better than inconsistency. Caro also naively resists the possibility that when the president of a large foie gras farm hosts a reporter on a tour, the president might not show the reporter everything. I hear the smoke-free tour of the cigarette manufacturing plant is also lovely and informative. At the end you get a sucker.