Are the Troubles in Northern Ireland finally over? Almost 21 years have passed since the Good Friday Agreement formally ended the conflict. Self-rule has replaced supervision from afar, and a return to the terrifying days of car bombs and masked gunmen is unthinkable. Yet the border separating the Republic of Ireland from the North has become a key sticking point in the continuing Brexit fiasco, and segregation persists between Catholics and Protestants. The factions continue to wave their flags and tend their murals with a dangerous pride. Like other societies recovering from internecine violence, Northern Ireland brims with shattered lives, and forgiveness seems generations away.

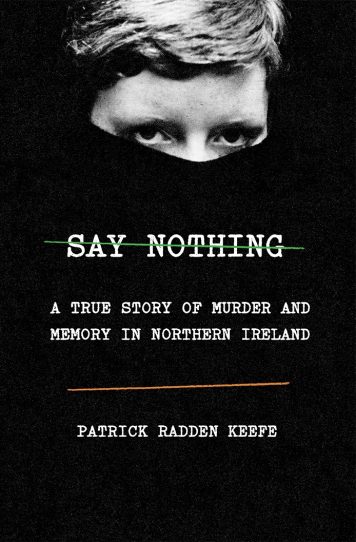

An exceptional new book, “Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland,” by Patrick Radden Keefe, explores this brittle landscape to devastating effect. Mr. Keefe is a talented writer for the New Yorker and an unaffiliated Irish-American. He grew up in Boston in the 1980s and never quite knew what to make of the contribution jars “for the lads” that he saw in pubs. “Say Nothing” renders his ambivalence into fierce reporting. Whereas previous histories of the Troubles by Ed Moloney and Brendan O’Brien could take on numbingly encyclopedic qualities, Mr. Keefe presents the conflict through narrative. He tracks the fatefully intersecting lives of three former leaders of the Irish Republican Army—Gerry Adams, Dolours Price and Brendan Hughes—and one of the paramilitary group’s victims, a widowed mother of 10 named Jean McConville, who disappeared in 1972.

McConville lived in Divis Flats, “a dank and hulking public housing complex” in West Belfast. Her late husband had been Catholic, but McConville was raised Protestant, and the mixed marriage drew harsh glares. One December evening approximately eight men and women burst into her apartment, some of them masked, and at least one of them armed, and took McConville away. The IRA later claimed she was an informer for British intelligence. A story—perhaps apocryphal—had it that she’d also once comforted a wounded British soldier in the hallway, cradling his head and saying a prayer over him. As she was led away, McConville told her 16-year-old son, “Watch the children until I come back.” She never returned.

The story of McConville’s disappearance, its crushing effects on her children, the discovery of her remains in 2003, and the efforts of authorities to hold someone accountable for her murder occupy the bulk of “Say Nothing.” Along the way, Mr. Keefe navigates the flashpoints, figures and iconography of the Troubles: anti-Catholic discrimination, atrocities by the Royal Ulster Constabulary and occupation by the British Army, grisly IRA bombings in Belfast and London, the internment of Irish soldiers and the hunger strikes of Bobby Sands and others, the Falls Road and the Shankill Road, unionist paramilitaries, the “real” IRA and the “provisionals,” counter-intelligence, the Armalite rifle and the balaclava. It is a dizzying panorama, yet Mr. Keefe presents it with clarity.

He also draws a vivid profile of Dolours Price (1951-2013), an IRA soldier and glamorous public personality who participated in McConville’s abduction and murder. (Mr. Keefe breaks news by placing Price’s sister Marian at the scene of McConville’s execution.) Price would come to resent the Good Friday Agreement and disavow Gerry Adams, her IRA commander, who in 1983 assumed the Republican movement’s leadership as president of its political arm, Sinn Féin. Price had committed acts of unspeakable violence at Mr. Adams’s direction, and she felt he’d betrayed her sacrifices by failing to achieve a united Ireland. Like her fellow soldier Brendan Hughes (1948-2008), Price was also a haunted former hunger striker. Both survived but, writes Mr. Keefe, “never stopped devouring themselves.”

“Say Nothing” features one of the most damning portraits yet published of Mr. Adams, the voice of modern Irish nationalism. In the 1970s he affected the posture of “a hip, if slightly pompous, public intellectual” who stroked his beard and smoked a pipe. Yet he evolved into a case study in moral hazard. Mr. Adams, now 70, has proved a master of evasion and dog-whistling, once famously answering a heckler who called “Bring back the IRA!” with a smirk and the words “They haven’t gone away, you know.” Shortly before dying, Price and Hughes each told interviewers Mr. Adams gave the order to execute McConville. He was arrested in 2014 but never charged. Yet Mr. Keefe reluctantly takes Mr. Adams’s side: Whatever his history of violence and monstrous duplicity, he ultimately moved republicanism in the direction of peace.

McConville’s children suffered “a life of merciless ostracism” after their mother disappeared. Shunned by their neighbors, the Catholic Church and even social services, they lived a “Lord of the Flies” existence for months on their own. Eventually the state divided them into prison-like orphanages, boys’ homes and workhouses, where several suffered physical and sexual abuse. Whatever one’s sympathies, the story of the McConville children is an appalling injustice. No political outcome can justify it.

In a bizarre twist, their mother’s fate came out in conjunction with an ill-conceived oral-history project launched by Boston College in 2001. Its organizers sought to record and archive for posterity the testimonies of Ulster’s former paramilitary fighters, including Price and Hughes. When the Police Service of Northern Ireland learned of the project, it partnered with the U.S. Justice Department to issue subpoenas for the taped histories. These stories proved either inadmissible or problematic for use in court, and Mr. Keefe never gained access to them. They nevertheless coincided with an era of closure for the disappeared of the Troubles.

Mr. Keefe’s greatest contribution in “Say Nothing” is to separate the romance of Irish nationalism from the horror of political terrorism. A priest said it best at the funeral of one of Jean McConville’s sons: Her abduction and murder was an “act of inexcusable wickedness” that plunged her family “into a lifelong nightmare.” Her children lived it. May their children live to see it end.