How’s this for an adventure: Buy a small airplane and learn to fly it. Point it east, toward the highest mountain range on Earth. Travel halfway around the world, solo, from England to Nepal, stopping to refuel in the great cities of Rome, Cairo, Baghdad and Delhi. Use subterfuge and luck to evade the police officers bent on stopping you. Descend, awestruck, as you approach the high Himalayas. Land on the flanks of Mount Everest itself—and then, with no experience of alpinism and no business among the towering seracs and screaming winds of that incomparable massif, attempt to become the first person in history to climb to the top.

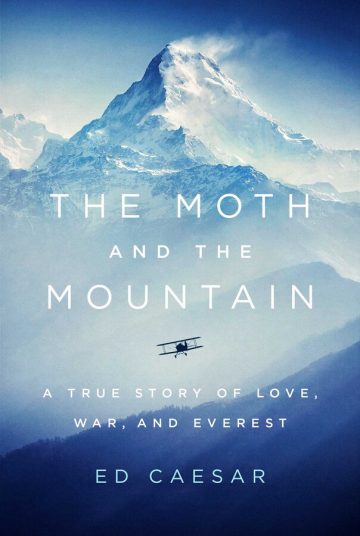

This tale of a “driven and defiant” amateur is true and presented with brio by Ed Caesar in The Moth and the Mountain. The book recounts the life of Maurice Wilson, a Don Quixote figure who in 1933 tried to vanquish the psychic wounds of World War I with a dazzling conquest. He wore elaborate costumes. He wrote florid love letters. The “Moth” of the book’s title is his four-cylinder biplane. Wilson always entered its cockpit from the left, “as he’d been taught, as if he were getting on a horse.”

The author, a contributing writer for the New Yorker, is a talented storyteller with a flair for detail. His subject’s absurdity is not lost on him. Yet Mr. Caesar also displays a handsome refusal to laugh at anyone’s dreams. Wilson did not, of course, summit Everest first; Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay claimed that honor 20 years later. But Wilson’s story is an entry less in the annals of mountaineering than in the Book of Life. That such an extraordinary person even existed is cause for celebration.

He was a seeker and a paramour, an optimist and a dandy. As with so many other young Englishmen of his generation, Wilson bore scars from World War I, physical and otherwise: He was decorated for valor under fire in an attack on his infantry unit in Belgium. Partially disabled and shell-shocked, he aimlessly traveled the globe after the war. A vague spiritual pilgrimage in 1932 landed him in Germany’s Black Forest, where he conceived the idea to reinvigorate his life by climbing Mount Everest.

It was a fashionable goal. Two major expeditions had sought, and failed, to conquer Everest in the 1920s. Their leaders were wild caricatures of masculinity. Charles Bruce, who led a 1922 attempt, reportedly exercised by running “up and down the flanks of the Khyber Pass, carrying his orderly on his back. As a middle-aged colonel he would wrestle six of his men at once. It was said by some that he had slept with the wife of every enlisted man in the force.” The lead climber in 1924 was George Mallory, who famously replied when asked why he wanted to climb Everest, “Because it’s there.” He died in the 1924 attempt after presumably ascending higher on Everest than anyone before.

These explorers found meaning in a combination of imperialistic conquest and spiritual journey. The yearning “to map every inch of the planet, to plant flags in remote and desolate places, had seemed like a high and patriotic calling,” Mr. Caesar writes. “But the early-twentieth-century desire for adventure also created—and was reflective of—a new way to understand the self.” Explorers like Bruce and Mallory went to the mountains seeking not just glory, but also “wisdom and enlightenment.”

That was the spirit of Wilson’s expedition. He enjoyed publicity, and fame would not have disagreed with him. But he mainly trekked east in search of what he could never seem to find elsewhere. True to form, Wilson bore a long-lived (and unconsummated) flame for his best friend’s wife, Enid Evans. Her lovely visage served as inspiration during the low moments of his quest. Wilson’s letters to Evans form the heart of the book; hers to him have sadly been lost. But he remained “the limelit hero of his own story,” Mr. Caesar writes, “and all of the complications and sorrows of his life were subsumed by the great adventure on which he was about to embark.” That he traveled by himself stood out to at least one modern alpinist: The legendary Italian mountaineer Reinhold Messner, who made the first solo ascent of Everest, in 1980, seemed haunted by Wilson. What connected the two men, Mr. Messner believed, was loneliness.

The two stages of Wilson’s trip were the flight and the climb. The flight was a game of cat and mouse with the British authorities, who wanted to avoid a public fiasco. They were always one step behind the amateur pilot, who delighted in the chase while barely keeping his plane aloft. At one point he was arrested, and at another he made a risky detour around Persia for lack of flyover rights. In Tunis Wilson filled his fuel tank with an unknown liquid from abandoned barrels, causing the engine to shudder and stall. More than once he fell asleep only to be awakened by the sound of his plane nose-diving toward the sea.

The Moth did not fly to Nepal as planned; police impounded it in northeastern India. From there, Wilson walked 300 miles to the mountain. To avoid attention, he disguised himself as a Tibetan priest, wearing a gold-brocade Chinese waistcoat, fur-lined Bhutia hat with earflaps, dark glasses and a parasol. “A ludicrous outfit. Wilson loved it.” Once he reached Everest base camp in April 1934, he celebrated attaining 19,200 feet with hopeless naivete: “Only 10,000 feet to go.” Wilson’s training of fasting and hill-walking in Wales was no match for the trial ahead. He had no crampons for traversing ice, no notion of a crevasse. Five days, he reckoned, would be sufficient to reach the top, in time for his birthday.

To give every detail of Wilson’s tenacious struggle upon Everest would be to spoil an outstanding book. His efforts gained world-wide attention, including a long article in the Times of London. It reported Wilson’s belief “that the man who would get up Everest was an Indian yogi, who had no possessions and was inured to hard and simple living.” After so many miles and so much dreaming, Wilson had boiled himself down to that essential spirit. If mountains could be climbed by willpower alone, he would have summited.

These days it is customary in outdoor circles to scoff at the foolhardy and the unprepared because they endanger others. That is a fair way to look at Maurice Wilson’s quixotic journey, but another perspective allows us to be grateful for a figure who looked heavenward and saw not barriers but open sky. The Moth and the Mountain returns readers to a romantic era when Everest was terra nova rather than an experience to be bought. It remained unvanquished. From the first page we know Wilson never stood a chance. But no one ever made a more dashing attempt.