Michael O'Donnell

Reader, Writer

Stamina Pays Off

February 10, 2023 | The Wall Street Journal

One of the best adventure books ever written begins with a failure. “The order to abandon ship was given at 5 p.m.” So opens Alfred Lansing’s “Endurance” (1959), the definitive account of Ernest Shackleton’s 1914 attempt to sail to Antarctica and cross it on foot. The eponymous ship was trapped in ice for nine months and eventually sank after being crushed by the pack. Shackleton and his crew of 27 had to paddle, march, hunt and shiver their way to safety, braving huge seas in smaller boats with the use of crude navigational instruments. Somehow, they all survived.

Lansing, an exceptional writer, described the party’s commander in legendary terms: “In ordinary situations, Shackleton’s tremendous capacity for boldness and daring found almost nothing worthy of its pulling power; he was a Percheron draft horse harnessed to a child’s wagon cart. But in the Antarctic—here was a burden which challenged every atom of his strength.” His leadership and willpower kept the men’s resolve intact through months of suffering, yet his optimism faltered after the loss of the Endurance. In his diary, Shackleton recorded the ship’s sinking and then the simple line, “I cannot write about it.”

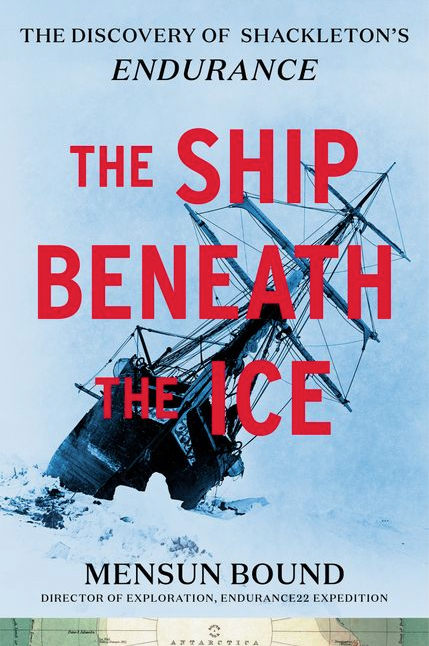

And now the Endurance has been found. In the most important nautical discovery since the Titanic in 1985, the Endurance was located and surveyed in March 2022, some 10,000 feet below the surface of the Weddell Sea. An international team of more than 150 deep-ocean researchers, engineers, ice scientists and meteorologists devoted two expeditions and untold resources to the project. The group’s director of exploration, the maritime archaeologist Mensun Bound, has written an engaging account of their efforts, “The Ship Beneath the Ice.”

The book returns readers to last year’s breathless discovery, when images and video of the ship were broadcast around the world with sublime clarity. The extreme cold water of the Antarctic, hostile to life, has preserved the wreck so well that even its paintwork and fastenings are clearly visible. Gobsmacked by the pictures sent back to the research vessel Agulhas by the project’s submersible, Mr. Bound writes that there “were no marine deposits; there was no corrosion. Everything was so fresh and clean. It was as if somebody had just scrubbed her up for this moment.”

Searching for the Endurance was primarily a historical rather than an archaeological pursuit, Mr. Bound asserts. Shackleton’s expedition, the ship and its destruction, were exhaustively described in crew-member diaries and chronicled by a photographer who traveled with the party. There is no lingering mystery as to how the Endurance became stuck or why it sank. “So, from a strictly archaeological point of view, it is hard to justify what we are doing,” Mr. Bound writes. Yet he contends that the wreck is a site of “outstanding cultural importance” representing the spirit of adventure. It deserves to be conserved for future generations. He even suggests that one day the technology might become available to recover the ship and display it to the public.

The bulk of the narrative describes the two expeditions to find the Endurance. The first, in 2019, lasted seven weeks and ended in failure after technical problems and bad weather. The crew aboard the Agulhas disastrously lost contact with their remote-piloted submersible as it scanned the ocean floor. As they attempted to recover it, the weather window for their search vanished and their own ship threatened to become moored in the ice. Mr. Bound vividly describes the looming presence of the pack. In late-summer the Weddell Sea is “a loose, jostling admixture of floes and brash, all melded into one by a thick, viscous, porridge-like slush.” But deadly icebergs hover nearby, including one that seemed bent on harm. “Huge, old, mute, somnolent, its face was smooth like a gravestone worn blank by time.”

The second expedition, in 2022, had better luck. Advances in submersibles technology offered more control to pilots as well as real-time video display. The team built its search area around the coordinates recorded by the Endurance’s captain, Frank Worsley, soon after the ship sank. Ice conditions in 2022 also cooperated more readily than in 2019. Still, Mr. Bound’s dramatic but entertaining descriptions of a modern ice-breaker at work remind readers of the hostile environment: “The vessel’s great rounded stem rises up and over the ice,” sometimes reaching more than 75 feet into the floe, “and then, like a wrestler performing a flying a body splash, comes slamming down with all its weight, crushing everything below and taking a bite out of the frozen slab” that can be up to 120 feet deep.

There is a lot of sitting around and waiting while the technicians scan the vast ocean floor. The crew play Ping-Pong and lament their ship’s dry bar of soft drinks and small beer. Mr. Bound seems to prefer Shackleton’s journal to the company of his confederates, and as a result misses a chance to fill out the portraits of his fellow explorers, who are sketched but not painted in. The best adventure books—Peter Matthiessen’s “Blue Meridian” (1971), about the search for the great white shark; or Jon Krakauer’s “Into Thin Air” (1997), about disaster on Mount Everest—revel in the physical, emotional and spiritual lives of the expedition team. While Mr. Bound graciously acknowledges the work of his collaborators, he fails to pay them the compliment of his pen’s attention.

The book’s climax comes only days before the second expedition must end. Mr. Bound narrates it thrillingly, giving the reader the sense of much more than the catch of a lifetime. Finding the wreck is the culmination of years of work by scores of people: “a point of perfect convergence when everything dissolved into a single, dizzying, incandescent sunburst of pure discovery.” There is also an intriguing passage describing Mr. Bound’s remote exploration of three holes carved into the main deck. These had allowed Endurance crew members to recover essential caches of food from the flooded hold after the order to abandon ship. Because Shackleton did not return with the salvage party, he himself never saw these changes to the Endurance that Mr. Bound first observed over 100 years later.

Despite the rush of success, a note of melancholy hangs over the story. Mr. Bound writes that the second expedition fared better than the first in part because melting sea ice allowed an easier passage: good news for the team but bad news for humanity. And a modern, high-tech search for ruins is inherently less gripping than the initial quest for glory in the heroic age of exploration. This leaves a sense that the greatest adventures are behind us. Yet what an adventure it was. If Mr. Bound and his colleagues rekindle interest in Shackleton’s expedition a century ago they will have done a service. This book is a good place to start. Lansing’s is even better.