In 1940 the young Henry Kissinger, caught in a love quadrangle, drafted a letter to the object of his affections. Her name was Edith. He and his friends Oppus and Kurt admired her attractiveness and had feelings for her, the letter said. But a “solicitude for your welfare” is what prompted him to write—“to caution you against a too rash involvement into a friendship with any one of us.”

I want to caution you against Kurt because of his wickedness, his utter disregard of any moral standards, while he is pursuing his ambitions, and against a friendship with Oppus, because of his desire to dominate you ideologically and monopolize you physically. This does not mean that a friendship with Oppus is impossible, I would only advise you not to become too fascinated by him.

Kissinger disclaimed any selfish motive for writing, loftily quoted from Washington’s farewell address, and regretted with some bitterness Edith’s failure to read or comment on the two school book reports he had sent her. Would she please return them for his files?

It is unfair to judge a man’s character by a jealous letter that he drafted (and did not send) at age sixteen. Yet here, to a remarkable extent, is the future nuclear strategist, national security advisor, and secretary of state. The reference to Edith’s attractiveness bespeaks the charm and flattery for which Kissinger would become famous. Secrecy and deceit are present also: he went behind his friends’ backs and coyly advised against a relationship with “any one of us,” which of course really meant the other guys. By trashing his buddies in order to get a girl, Kissinger displayed ruthlessness. The letter is written in what Christopher Hitchens memorably described as Kissinger’s “dank obfuscatory prose,” which relies on clinical-sounding phrases like “dominate you ideologically.” And, of course, the letter betrays vanity. How could anyone fail to be dazzled by his book reports!

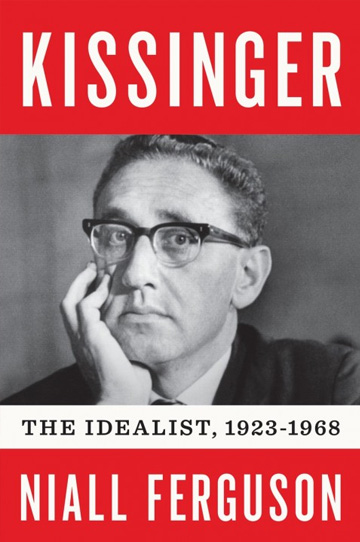

The conservative historian Niall Ferguson presents this letter in Kissinger: The Idealist, 1923-1968, the first volume of his massive two-part biography of the controversial statesman. Yet Ferguson reads the letter and reaches a different conclusion. It stands out, Ferguson writes, not because it reveals unsavory character traits that Kissinger would display throughout his public life, but for its “analytical precision and psychological penetration.” Ferguson concedes that the letter is “solipsistic,” and the product of youthful jealousy. Yet he cannot help but admire the young strategist at work: even the boy Kissinger could analyze a series of interlocking relationships, parse the competing interests, and make a power play.

Ferguson is Kissinger’s authorized biographer, and in 1,000 pages he begins the task of rescuing his subject’s tarnished reputation. It is a steep climb. The foreign policy chief for Presidents Nixon and Ford has been portrayed in dozens of books and by countless witnesses as a coddler of dictators, a cynical practitioner of realpolitik, a war-monger, a suck-up to superiors, and a tyrant to subordinates—his genius and wit matched only by his underhandedness. Hitchens’s The Trial of Henry Kissinger is the most entertaining such book, but unbecoming portraits also appear in prominent works by Seymour Hersh, Robert Dallek, Margaret MacMillan, and, most recently, Greg Grandin, whose Kissinger’s Shadow just arrived in August. Woody Allen had his say in the mockumentary Men of Crisis: The Harvey Wallinger Story, and so did the novelist Joseph Heller, who described Kissinger as “an odious shlump who made war gladly.” Kissinger’s leading biographer, Walter Isaacson, was less hostile but still cutting, summing up Kissinger as “a brilliant conceptualizer” who was “slightly conspiratorial in outlook.” He “could feel the connections [between far-flung events] the way a spider senses twitches in its web.”

What drives this animosity—especially toward a man who used to be widely admired? Ferguson has several theories. Perhaps it is envy. Kissinger coined many bon mots and had a way with women; the haters may simply be jealous. Another possibility is that the many witnesses against Kissinger had axes to grind—although this begs the question whether Kissinger’s own behavior invited the axes. Ferguson also perceives anti-Semitism at work. There is somewhat more substance to this charge. Kissinger’s family fled Nazi Germany for the United States in 1938, and he became a conspicuous butt of jokes in the casually prejudiced Nixon White House: the professor with the curly hair and the funny accent. Yet it is worth pointing out that Kissinger’s two most ferocious mainstream critics, Hitchens and Hersh, were themselves Jewish. More than that, it feels manipulative to play on our sympathies for a man who famously has so little sympathy for others.

The subtitle of this volume gives some indication of what Ferguson is missing in his psychoanalysis of Kissinger’s critics: The Idealist. The author’s revisionist thesis is that Kissinger was not in fact a realist, as he is so frequently portrayed. Hence Ferguson provides lofty epigrams from his subject to begin his chapters, such as this one: “It is true that ours is an attempt to exhibit Western values, but less by what we say than by what we do.” He shows us Kissinger moralizing against the use of “small countries as pawns” in the game of global strategy. Ferguson even quotes Kissinger privately scolding the Kennedy administration (those “unscrupulous pragmatists”) for tacitly authorizing the assassination of South Vietnam’s Ngo Dinh Diem: “The honor and the moral standing of the United States require that a relationship exists between ends and means.… Our historical role has been to identify ourselves with the ideals and deepest hopes of mankind.”

Horseshit. By reproducing these quotations with a straight face, Ferguson has made himself a hypocrite’s bullhorn. The ideals and deepest hopes of mankind? Kissinger and Nixon bombed Cambodia to pieces in a secret four-year campaign that annihilated some 100,000 civilians. “Anything that flies, on anything that moves,” were the parameters Kissinger gave to Alexander Haig. He countered African liberation movements by embracing the white supremacists of Rhodesia and South Africa, a policy known as the “Tar Baby option.” Kissinger facilitated the overthrow of the governments of Chile and Argentina by right-wing generals, and then worked tirelessly to deflect criticism of the new governments’ torture and murder. A declassified memorandum of his meeting with Augusto Pinochet in 1976 shows Kissinger in a particularly unflattering light: “We welcomed the overthrow of the Communist-inclined government here. We are not out to weaken your position.” In 1975 Kissinger and President Ford met with Indonesian strongman Suharto and authorized him to invade East Timor, which he promptly did the following day; another 100,000 lost their lives. “It is important that whatever you do succeeds quickly,” Kissinger advised.

Henry Kissinger is entitled to a defense, but outfitting him in the white robes of idealism is not the way to go about it. Tellingly, at several points in the narrative Ferguson strays from his thesis and defends Kissinger on more utilitarian grounds: the Cold War was real, its outcome was uncertain, and the United States needed every ugly advantage it could find on the geostrategic battlefield. The crimes of communist regimes vastly dwarfed Kissinger’s in scope and scale, Ferguson writes. That is fine as far as it goes, but when Ferguson takes this line further, the reader begins to squirm:

[A]rguments that focus on loss of life in strategically marginal countries—and there is no other way of describing Argentina, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Chile, Cyprus, and East Timor—must be tested against this question: how, in each case, would an alternative decision have affected U.S. relations with strategically important countries like the Soviet Union, China, and the major Western European powers?

It is a fair question, if callously put. Having set the terms of debate, Ferguson is now on the hook for his next volume to weigh the strategic implications of Kissinger’s most barbaric foreign policies once he assumed power. Ferguson must explore the impact that reining in Suharto rather than stepping aside might have had on the U.S.-Indonesia alliance, and on broader Cold War dynamics. He must analyze what would have become of Chile and Latin America more broadly had the United States not engineered the overthrow of Chile’s democratically elected government in favor of the fascist Pinochet. And not to overlook Kissinger’s strategic boners: Ferguson must consider the implications for the Middle East over the past forty years had Kissinger not inaugurated the policy of wholehearted support for the Shah of Iran in the early 1970s. The answers had better be good.

Kissinger begins in a defensive posture, with the author anticipating that because Kissinger asked him to write the book, readers will assume he was “influenced or induced to paint a falsely flattering picture.” It is true that an authorized biographer must win his reader’s trust. But Ferguson’s problem is not a conflict of interest: it is his ideological affinity with his subject, and his determination because of that affinity to present his man favorably. This begins with Ferguson’s use of language, which repeatedly seeks to bring the reader onto Kissinger’s side. Here are a few representative examples: “Never one to shirk the front line,” Kissinger set off on a fact-finding trip to Vietnam. That country “awakened the man of action long dormant inside the professor.” “Even more impressive” than the depth of his knowledge “is Kissinger’s brilliance as a prose stylist.” As a lowly State Department consultant, “he was required to fly economy the whole way” to Hong Kong. Poor Dr. Kissinger!

Ferguson spends much of the book attempting to rehabilitate Kissinger’s character. He makes an unpersuasive attempt to convince readers that Kissinger was not the relentless ladder climber we think we know. As a graduate student and then a professor at Harvard in the 1950s, Kissinger edited the journal Confluence and organized the university’s International Seminar. Various writers have noted that this work put Kissinger in touch with leaders-on-the-make from around the world: future foreign secretaries, journalists, and policymakers. Yet Ferguson maintains that Kissinger was above such considerations. “A more plausible conclusion is that Kissinger sincerely saw the two parallel ventures as the most effective contributions he could make to a psychological war against Soviet communism to which he was sincerely committed.” No fewer than five future prime ministers attended the seminar in the 1950s and ’60s, and Kissinger made a point of inviting luminaries like then Vice President Nixon. But Ferguson seems to think he was too idealistic to network.

The book also largely sidesteps the topic of Kissinger’s famous vanity, thin skin, and penchant for insincere flattery. (This is a man whose memoirs are longer than the combined memoirs of Presidents Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Carter, and Reagan.) Yet when Ferguson addresses Kissinger’s interpersonal traits, it is usually to defend his subject. For instance, Kissinger left academia to advise Nelson Rockefeller on foreign policy throughout the 1960s as the moderate Republican repeatedly sought his party’s presidential nomination. Both of Rockefeller’s biographers, Richard Norton Smith and Cary Reich, portray Kissinger as obsequious to his boss’s face (Smith: “deferential to the point of sycophancy”; Reich: “downright fawning”) yet derisive about him when Rockefeller was not around. We know from many witnesses that a similar pattern prevailed between Kissinger and Nixon the following decade. Yet Ferguson is not convinced: “This does not ring true. Theirs was a turbulent friendship.” Reich cites two separate eyewitness accounts, but Ferguson dismisses them without explaining why they should be disbelieved.

Ferguson concludes this volume with a revisionist telling of Kissinger’s infamous maneuverings during the 1968 presidential election. Hersh was the first to write—and Isaacson and others have verified—that after Rockefeller dropped out of the race, Kissinger provided the Nixon campaign with inside information about the progress of the Vietnam peace talks then under way in Paris. Kissinger had contacts on the staff of the U.S. delegation, and he pumped them for details. He learned that a deal was coming together: Lyndon Johnson would halt the bombing of North Vietnam, and in return North Vietnam would finally come to the table. Kissinger provided information and analysis to Nixon’s aide Richard Allen in breathless telephone calls, which he insisted be kept secret. Nixon’s campaign subsequently passed word to the South Vietnamese government that it could obtain better peace terms under a Nixon administration. South Vietnam pulled out of the talks just days before the U.S. election, the Democratic Party was humiliated, Nixon won the presidency—and then he immediately appointed Kissinger, a man he had met only once, his national security advisor.

Many witnesses have confirmed the main contours of this account, including Richard Holbrooke, a staffer for the U.S. delegation to Paris; John Mitchell, H. R. Haldeman, and Richard Allen of Nixon’s staff; and Nixon himself, who wrote about Kissinger’s efforts in his memoir. Johnson referred to the maneuver—spiking a peace deal in order to win an election, thereby extending the Vietnam War—as treason. Yet Ferguson again is not convinced. He questions Allen’s reliability as a witness and contends that Nixon’s memoir does not prove that Kissinger was his insider. (Decide for yourself. Here is Nixon: “During the last days of the campaign, when Kissinger was providing us with information about the bombing halt, I became more aware of both his knowledge and his influence.”) Ferguson also makes the legalistic argument that Kissinger’s intervention was not determinative, for Nixon had other informers, and North Vietnam “would surely” have found a pretext to abandon the peace talks had South Vietnam not walked out first. If we use Johnson’s terms, I suppose that reduces the charge to attempted treason.

Ferguson also writes, “If Henry Kissinger really was so keen for a government job after the 1968 election, was leaking sensitive information about the Vietnam negotiations to Richard Nixon—who was by no means guaranteed to win—the obvious way to get it?” The first response to this strange rhetorical question is to point out that no presidential candidate is guaranteed to win an election. The second is to note that Kissinger hedged his bets, simultaneously approaching the campaign of the Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey and dangling files of opposition research on Nixon, whom he claimed to loathe. (One of Humphrey’s staffers called this double dealing “grotesque.”) And the third response to Ferguson’s question is to emphasize the opportunistic nature of Kissinger’s movements. He had picked another candidate in Rockefeller, but Rockefeller lost his party’s nomination. So Kissinger set about wooing the Republican and Democratic candidates in any way he could. Ingratiating oneself to both presidential campaigns at the eleventh hour seems like exactly the way to get a government job.

Kissinger’s complete legacy is beyond the scope of Ferguson’s book, which ends just before Kissinger assumes power in 1969. But it is the subject of Greg Grandin’s Kissinger’s Shadow. Grandin, a historian at New York University, contends that Kissinger has left us with war as an instrument of policy, less as a last resort than as a kind of peacock’s strut. “Kissinger taught that there was no such thing as stasis in international affairs,” Grandin writes. “[G]reat states are always either gaining or losing influence, which means that the balance of power has to be constantly tested through gesture and deed.” (He quotes Kissinger as asking a fellow cabinet member, “Can’t we overthrow one of the sheikhs just to show that we can do it?”) The abiding concern driving Kissinger’s foreign policy was therefore maintaining credibility: action to avoid the appearance of inability to act. Hence, Grandin persuasively argues, the bombing of Cambodia is Kissinger’s signature policy, supported as it was by a self-perpetuating justification. Kissinger helped scupper the Paris peace talks in 1968, and then when the talks were set to resume, the United States needed to show its resolve—so it began bombing Cambodia. In secret.

Secrecy is very much a part of Kissinger’s legacy. His systematic efforts to keep the war in Cambodia from becoming public—false records, wiretaps, blatant lies told to Congress—are much more disturbing than the fourth-rate jiggery-pokery of Watergate. Ferguson downplays this too, projecting his disagreement by writing disdainfully that “we are told” Kissinger loved secrecy. Perhaps Ferguson could prove his point by finding the client list of Kissinger Associates, the business consultancy that facilitates relationships between corporations and governments, often in the world’s nastiest places. Sometimes diplomacy requires secrecy, as when Kissinger took elaborate steps to hide his advance visits to China in preparation for Nixon’s historic meeting with Mao. But sometimes secrecy merely serves domestic political purposes—and sometimes it lubricates the accumulation of power. By the time Secretary of State William Rogers learned that Kissinger was conducting the nation’s foreign policy without even notifying his department, it was too late to stop him.

It would be unfair to discuss Kissinger’s legacy without mentioning his triumphs: the opening to China, nuclear nonproliferation agreements, and diplomacy in the Middle East during the Yom Kippur War of 1973. Yet I suspect the abiding image of Kissinger will come from Hitchens, who observed Kissinger panicking in 1998 after learning that the federal government planned to release details of Pinochet’s killings and torture—and that this might implicate him. “Sitting in his office at Kissinger Associates, with its tentacles of business and consultancy stretching from Belgrade to Beijing, and cushioned by innumerable other directorships and boards, he still shudders when he hears of the arrest of a dictator.” Realpolitik is ugly business. And for Henry Kissinger, business was good.