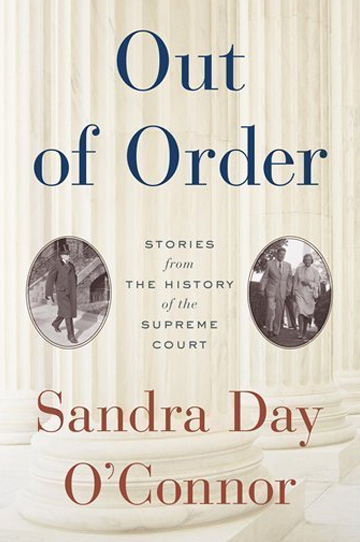

When Sandra Day O’Connor retired from the Supreme Court in 2006, she was the most famous judge and most powerful woman in America. Appointed by President Reagan in 1981, she had been the first female justice in the Court’s history. She was also its swing voter, a moderate conservative who preferred pragmatic solutions over her colleagues’ devotion to almighty principle. A strong and astringent personality — like an aunt who interrupts the pleasantries to ask about your sex life — O’Connor has led an active retirement. She has heard cases as a visiting judge on eleven of the thirteen federal courts of appeal, promoted civics education, and championed the independence of elected state judges. Her latest project is a book, her third, entitled Out of Order: Stories from the History of the Supreme Court.

It is a pleasant but limited affair. O’Connor is an outspoken straight talker, but despite its suggestive title Out of Order is as guarded and cautious as confirmation testimony. Freed from the strictures of office, she might have written candidly about her personal experience on the bench — as her colleague John Paul Stevens did after retiring in the outstanding 2011 memoir Five Chiefs. From the very middle of the Court, O’Connor had the best vantage point to observe the major cases of the last generation. Surely she has stories to tell.

Instead she provides moderately interesting but never juicy trivia from the Court’s past and present: the practice of “riding circuit” in the 1800s, whereby justices performed duties as lower-court judges across the country; the Supreme Court’s itinerant existence before moving to permanent facilities at One First Street; a handful of jokes from the courtroom. Chapter Eight portentously begins, “As the Supreme Court has evolved from its early days to occupy a critical role in our democratic society, the Justices have developed various customs and traditions.” The one justice whom O’Connor openly criticizes is the notorious bigot James McReynolds, a man so anti-Semitic that in 1932 he made a show of reading the newspaper while his colleague Benjamin Cardozo was sworn in. But everyone hates McReynolds. Panning him is about as interesting as panning Caligula. There is little here that is not available in Smithsonian pamphlets and guided audio tours.

Little — but not nothing. O’Connor modestly declines to quote herself, with one exception. “A state of war is not a blank check for the President,” she wrote in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld (2004), which forced the Bush administration to provide enemy combatants with due process. We can infer from its inclusion that O’Connor’s opinion in Hamdi is one of her proudest achievements. O’Connor also tellingly remarks, in a chapter on the Court’s uncertain first decade, that the Court “is only as effective as people think it is” — a nod to recent scholarship on the influence of public opinion on the judiciary’s work. O’Connor is a former state legislator, and she understands better than most that straying too far to either political extreme imperils the Court’s legitimacy. It is a recipe for centrism and compromise: values that O’Connor lives by, but which have become increasingly hard to discern on the legal landscape.