A century ago, as the excitement of the Wright Brothers faded and the smoke from World War I cleared, a question arose: What was the future of the airplane? Few Americans had ever seen one; those who had knew it as little more than a barnstorming novelty. Planes had proven their utility in war, but not yet in peace. After the armistice, the Army’s Air Service thinned out its ranks from 20,000 officers down to 1,300. The Boeing Co. pivoted to making furniture and speedboats. One of the first aeronautical engineering specialists at MIT advised an eager student to seek another field. “This airplane business will never amount to very much,” he predicted.

Yet a few visionaries saw commercial and strategic promise in American aviation. As European governments supported their own fledgling industries, these individuals sought a gimmick to spur public interest and, more importantly, congressional appropriations. Pilots made themselves useful scanning for forest fires, mapping cities, dragging advertisements and even patrolling the border. When these ideas didn’t take hold, aviation boosters put together a cross-country race that, for a few weeks in 1919, would capture the country’s imagination at the dawn of the age of flight.

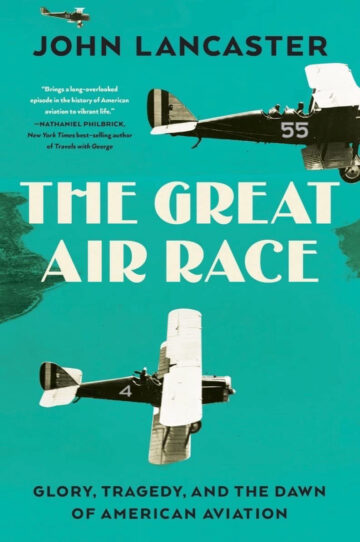

Journalist and pilot John Lancaster tells this story in “The Great Air Race,” a compelling book that succeeds by giving this chapter in history its due without overselling its significance. The transcontinental air race of October 1919 did not usher in modern aviation; in fact, it may have scared away more passengers than it attracted. But it demonstrated “what an air transportation system would actually look like,” Mr. Lancaster writes. “No one who followed the contest could seriously doubt that the airplane would soon join the passenger train, the steamship, and the automobile as a practical feature of everyday life.”

The contest’s impresario, vividly brought to life in these pages, was Brig. Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell. He came to believe in the promise of aviation after coordinating the Allied air forces at the Battle of St. Mihiel in 1918. Brash, pompous and arrogant, Mitchell alienated many a superior officer. Resplendent in breeches and a bespoke shirt with giant pockets, he carried a leather riding crop and a handkerchief to polish his boots. Stirringly, he designed his own crest—a silver eagle on a scarlet disc, inspired by the Great Seal of the United States —and had it painted on his airplane as his personal insignia. As he sailed home from the war aboard the cruise ship Aquitania, he strode the deck on his daily inspection, accompanied by a retinue of aides. The Chicago Tribune observed: “No one ever had a better time being a general.”

For all his vainglory, Mitchell was onto something in betting on a race as an aeronautical showcase. As Mr. Lancaster explains, Mitchell would use the event to promote the establishment of a permanent air force to exist alongside the Army and Navy. (“It was easy to imagine who Mitchell had in mind to run the new branch of the armed forces,” Mr. Lancaster writes.) In a test-race in July 1919 between New York and Toronto, Mitchell saw how a large-scale contest could become a beacon for publicity at the intersection of news, technology and commerce. Pilots starting in New York carried copies of newspapers to bring to Toronto, as well as a letter from Woodrow Wilson to the Prince of Wales, who was touring Canada.

These deliveries introduced an improbable element into the notion of long-distance airplane racing: the mail. Another of the transcontinental race’s boosters was Otto Praeger, a postal official charged with getting airplanes in service for long-distance correspondence. Yet the very notion of airmail seemed cursed. Its first flight, in May 1918, began with pilot George Boyle departing Washington and accidentally heading south toward Maryland instead of north toward Philadelphia. His cache of mail had to be shipped less colorfully, by train. The pilot would be forever known as Wrong Way Boyle.

Such a mistake was understandable in an era of “crude flight instruments” and open cockpits, before the invention of radar or air traffic control. Many of the pilots in the transcontinental race would fly DH-4s left over from the war, nicknamed “flaming coffins” for their tendency to catch fire. Unsuitable planes were just one of the problems the entrants faced once the race began. Pilots frequently lost their way and had to land and ask for directions, while unreliable maps and infrequent airstrips made each descent a gamble. Any fix at hand served to keep their planes in the air—cornmeal could plug a leaking radiator—or on the ground, as when one crew member leapt off his plane and dragged his boots in the earth to help slow it to a stop.

Competing entrants—more than 60 in all—departed from airfields on both coasts. Most took off in Long Island and headed west; a smaller number began from San Francisco to trace the route in reverse. Once each plane reached the opposite coast, it turned around, crossing the country not once but twice. Along the way, pilots made nightly stops to eat, sleep and refuel. The race generated a media bonanza, with national newspapers covering the event and profiling the various personalities. Foremost among them was the eventual winner, Belvin Womble Maynard, who completed the race in just over 50 hours of flying time. A Baptist minister by profession, he earned the nickname “the Flying Parson,” logging the miles with his German Shepherd, Trixie. “Parson, the sinners are with you,” called one well-wisher in Salt Lake City.

But if the contest began as a sensation, it became a fiasco. The decision to hold it in October meant unpredictable weather; storms enveloped the airplanes over the mountain west. Doubling the race’s length by adding a return trip was a last-minute decision made without forethought. Above all, the pilots flew aircraft that had no business traveling thousands of miles. Ultimately, 54 planes crashed and nine pilots died—two of them on the way to the starting line. The Flying Parson faded from hero to scold, using his new celebrity to moralize against low necklines and drink. “He was pretty blunt with those who would touch the hem of his garment,” wrote one reporter, “very nearly as surly as Lindbergh.”

Mr. Lancaster concludes that the transcontinental air race did little for airmail, which fizzled out in 1927, while its chaos hardly reassured tentative passengers. But it did underscore “the rapid advance of airplane technology,” serving as “the first iteration of a new age.” Above that, the pilots were pioneers whose exploits are worth remembering. At a moment when air travel has become a nightmare of flight delays, missed connections and vanishing legroom, it is refreshing to return to an era when taking to the skies meant adventure and freedom.