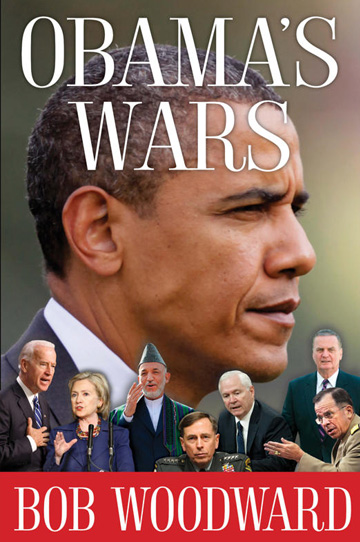

Obama’s War

October 5, 2010 | Christian Science Monitor

Teachers of the world, relax: Bob Woodward is here to tell us about verbs. One of the main themes of his new page-turner, Obama’s Wars, is the unending battle among the mucky-mucks and Pentagon brass over the correct action verb to describe the United States’ mission in Afghanistan. Helpfully, for purposes of retention, it is an alliterative problem. Does the United States wish to “defeat” the Taliban, or merely “disrupt” it? Dismantle or degrade it? Surely not destroy it? Toward the book’s end the reader sighs at the resolution of this dilemma, which could occur with straight faces only in Washington, which immortalized phrases like “nattering nabobs of negativity” and “boob bait for the bubbas.” President Obama ultimately defines the policy in Afghanistan thus: The United States will reverse the Taliban’s momentum and then deny, disrupt, and degrade it. What exactly the Taliban will be denied is left to the reader’s imagination, but your reviewer conjured up the image of a Shaq-like defensive swat at the rim: denied!

It turns out that Obama’s Wars is not much of a page-turner after all, certainly not by Woodward’s standards. In The Brethren (1979) he unloaded reams of juicy gossip about a little-understood institution, the Supreme Court. In Bush At War (2002), he wrote a breathless drama, impossible to put down, about the frantic weeks following September 11, 2001. Even Plan of Attack (2004) was exciting: It chronicled the fateful decision to invade Iraq, revealing the thinking behind a controversial policy whose rationales have shifted over time. The line on Woodward is that even if his writing is stiff and his pervasive use of anonymous sources maddening, his books broadly capture in real-time the personalities and intrigue behind secret government decisionmaking.

In contrast to his best books, Obama’s Wars is a slog. It suddenly begins on page 1, and just as suddenly ends on page 380, like a rainstorm – or a headache. There is little analysis or sense of narrative; it feels as if Woodward merely assembled in chronological order nuggets and anecdotes from his many sources, diary-style, and then said to his agent, “Sell it!”

The decision over what to do with a stale, inherited war that is going badly – a decision that is by nature complicated, bureaucratic, technical, and dry – does not make for high drama. The bulk of the book concerns a series of meetings of Obama’s national security team over whether to have a surge in Afghanistan, and if so, how many troops to send. These are matters of life and death, but somehow in Woodward’s rendering they become abstractions. Should it be 20,000 troops or 35,000? Or 40,000? At a certain point these options begin to look meaningless. With no reporting from the ground in Afghanistan or Pakistan – or for that matter from Veterans Administration hospitals – Woodward removes the stakes. His book is not about war; it is about process, chain-of-command, bickering, power-plays, and PowerPoint slides.

During the meetings, Obama grows a little tired of all the numbers too, and wonders if his military advisers aren’t missing the bigger picture. Generals David Petraeus and Stanley McChrystal, along with Admiral Mike Mullen, insist that they need 40,000 troops, a full-on counterinsurgency plan, and six to eight years more to conquer Afghanistan. Sometimes they say this, unauthorized, before television cameras, incensing the president and his staff. For his part, Obama coolly questions their reasoning, seeks evidence for their claims, and stews over the Chicago-school notion of opportunity cost: With every billion dollars spent on Afghanistan, he foregoes important priorities for the country at home. He will not give up an important fight, but insists on realism now that nine years have shown the limits of American power in Afghanistan.

Woodward sketches presidents well, mosaic-style. His George W. Bush was a gut-based, shoot-from-the-hip delegator, all nicknames, belt-buckles, and backslaps. If the generals asked for 40,000, that’s what they got. Obama’s Wars suggests – without claiming outright – that Bush’s way of running things was an abdication of the civilian control of the military, a principle that Obama has reasserted. Obama respects his generals’ judgment, but never forgets that the decision is his, and cannot be made in a vacuum. With the support and encouragement of Vice President Joe Biden – who emerges, somewhat improbably, as an adviser of very fine judgment – Obama listens to the differing views for months and then firmly ends the debate. Here’s what we’re going to do, he says, and then sits down and drafts the policy himself, an unprecedented gesture. It will be 30,000 troops, and they start coming home in July 2011. That’s an order.

With a climax like that, Obama’s Wars is more than anything a study in leadership and management style. Obama emerges as cerebral, analytical, and confident enough to inject his own judgment into decisionmaking. It is a reassuring image in an uncertain time. But will the surge work? One of Woodward’s sources is skeptical: “Obama had to do this 18-month surge just to demonstrate, in effect, that it couldn’t be done.” The first official review of the policy occurs in December 2010. Expect another book from Woodward shortly thereafter.