My Captain Jacks

June 19, 2020 | The Wall Street Journal

I don’t know anyone else who’s got a tailor-made work of art. Not tailor-made in the sense of a commissioned piece or a personal gift. I’m not referring to dedicatees. Nor do I mean favorites. Everyone has favorites. I mean stumbling across a film or novel that is pitched so finely to your particular sensibilities that encountering it is like discovering a twin sibling. You understand that it will be a part of your life from that point onward. The closest I’ve come to meeting another person who’s had this eerie good fortune was my grandfather, whose love for the music of Sergei Rachmaninoff was extraordinary to behold. He would sit in his rocking chair and close his eyes as the sound washed over him. From the expression on his face, you would almost think he was in pain. But those who knew him well understood that the look was rapture.

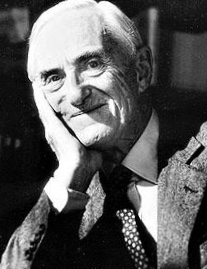

It is great good luck to find one’s artistic soul mate, if that is the proper shorthand for this phenomenon. So much the better that the work in question should be bountiful rather than slender. Rachmaninoff wrote only four piano concertos—five, if you count the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. In that respect I can only count my blessings. My artistic soul mate is a 20-volume series of novels that runs to nearly 7,000 pages and was written over the course of 30 years: the Aubrey-Maturin series by Patrick O’Brian. The books depict life in the Royal Navy during the age of sail. Some will know of them through a fine film adaptation by Peter Weir called “Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World” (2003). I recently finished the 20th and last novel in the series after nearly nine years of reading. This will sound maudlin—it is maudlin—but as I completed the final volume I closed the book, kissed its cover, and wept.

Here I should make an important disclosure. I care nothing at all for boats or the sea. I don’t even like to take a bath. But to me Aubrey-Maturin is not about the water. It is about friendship. The series chronicles one of literature’s great love affairs, worthy of mention alongside Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. One party is Captain Jack Aubrey: lifelong Navy man, hearty of appetite and strong of voice, with a wandering eye but a sentimental heart; a fighting captain with a bold way and a lucky streak yet a strict insistence on custom and tradition, even going so far as to wear his hat athwartships in the manner of the great Lord Nelson. Aubrey’s particular friend is Stephen Maturin: physician, naturalist, republican, British intelligence agent; a cosmopolitan linguist with Irish and Catalan lineage; careless in appearance and cold of manner; lethal with a pistol when called out to duel; yet capable of the most tender sympathies for his family and friends, and most of all for the man he calls brother.

O’Brian follows Aubrey and Maturin around the world many times over, from early adulthood to the onset of old age. The opening scene of the first novel, “Master and Commander” (1969), is a sort of meet-cute, as the two are seated next to each other at a chamber-music concert. Aubrey enthusiastically beats out the time, disrupting Maturin’s cerebral effort to follow the composer’s train of thought. The final scene of the last novel, “Blue at the Mizzen” (1999), has Maturin delivering long-awaited good news: Aubrey has at last been given command of the fleet. “May I too congratulate you, Admiral dear?” asks Stephen, embracing Jack, who is nearly unmanned by the news. In between these two scenes the reader encounters a lifetime of friendship: marriage, children, fallings-out, reconciliation, the death of a spouse, war, peace, feasting, laughter and music.

Is there music. Its magic has seldom been captured so well on the two dimensions of the rectangular page. Stephen plays the cello and Jack plays the violin; they spend many an evening in duet. Here, to take one of countless such passages, is Stephen’s response to Jack’s familiar invitation to play an old standby, the Corelli violin sonata in C major. The two friends have no audience; they are not performing. They are simply making music together:

“With all my heart,” said Stephen, poising his bow. He paused, and fixed Jack’s eye with his own: they both nodded: he brought the bow down and the ’cello broke into its deep noble song, followed instantly by the piercing violin, dead true to the note. The music filled the great cabin, the one speaking to the other, both twining into one, the fiddle soaring alone: they were in the very heart of the intricate sound, the close lovely reasoning, and the ship and her burdens faded far, far from their minds.

Soon after I began reading O’Brian in 2011 I did something out of character. Not 50 pages into the first book I found a leather-bound, heirloom set from the Easton Press with gilt-edge pages and inlaid satin bookmarks and I subscribed. I don’t recall the price—Easton Press no longer sells this edition—but it was around $2,000, and you can spend almost twice that for it on the secondary market today. The volumes are of uniform size and a splendid navy blue color, with spines and boards built to last in the finest traditions of Gutenberg. The paper is of a rich stock, each page nearly as thick as a greeting card. I don’t think I encountered a single typo in my entire journey through the series. Such a fine set would be the pride of any bookshelf; certainly it is the centerpiece of mine. Making the purchase so soon into the first volume was a decisive act taken in recognition of a known thing. I knew I would read every last book and hand the set down to a son or daughter one day.

I began to race through the series, enchanted with its rhythms and its characters, its humor, quirks and boundless curiosity with the the world and the people in it. Stephen despite his years at sea could never manage ingress or egress of a man-of-war and often contrived to fall between the ship and the jolly boat. Jack delighted in a corny pun but usually lacked the wit to bring one off in the moment. O’Brian (1914-2000), whose nonfiction works include a life of Joseph Banks, describes the natural world, and animals in particular, in the richest, most vivid prose, like sea elephants “whose enormous males as I am sure you know wear a fleshy great proboscis and rearing up utter a hellish roar.” The books’ very language began to seep into my own speech: the fine great prodigious strings of adjectives, unbroken by commas. Jack’s bathing “mother naked” in the sea. Idioms and sayings like “for all love,” “God’s my life,” “Hell and death” and “all a-hoo.” Another O’Brian fan I once knew was particularly fond of using that last expression when everything fell apart. His first invocation of it endeared him to me permanently.

Soon enough I began to slow down my consumption of these exceptional novels, rationing them out like treasured bottles of Scotch meant to last a long voyage. Twenty volumes sounds overwhelming until it begins to sound like not nearly enough. I found that their quality lent itself to a slower pace. They are not swashbuckling pulp productions, as their subject matter might suggest; the novelist I have seen O’Brian compared to most frequently is Jane Austen. So, after an early sprint, I started to save my leather-bound volumes for vacation reading, and eventually allowed myself only one per year. If my wife saw that I was low in spirits, or overworked, or burdened by life generally, she would say, “Why don’t you read one of your Captain Jacks?” The suggestion was always well-timed, and gratefully accepted.

It is difficult to find words for what these books—my artistic soul mates—mean to me. They lack the interactivity of a flesh-and-blood relationship, and of course I would never place their value on the same plane as one of the people near to my heart. But in the next tier of life’s treasures they have come to represent for me the value of reading itself. In their company I have found solitude but never loneliness, wordplay, knowledge, yearning and imagination, not to mention the tactile pleasures of a durable object in my hands, with light playing over a page dancing with serifs. I have laughed as often as I have cried. I have smelled the pots of coffee that have revived Jack and Stephen in the morning, and tasted their toasted cheese on my burnt tongue as they finished an evening. Above all I have understood friendship: their friendship, and my friendships. With the help of these books I have better appreciated my own friends and vowed to ensure I earn their esteem.

Twenty volumes and 7,000 pages has an upside. By the time you have finished the series, your memory is not what it used to be. For me that means it’s time to return to the beginning and start the journey again.