Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s parents fell in love, married, and produced an egghead. He wore eyeglasses and a bow tie. He spoke in perfectly formed sentences. At the age of twenty-eight he won his first Pulitzer Prize, for a biography of Andrew Jackson. Fifteen years later he entered the White House for the defining experience of his life: service to John F. Kennedy as a special assistant to the president. Schlesinger revered Kennedy, gave him his best years, and was devastated by his murder. His letter to Jacqueline Kennedy on November 22, 1963, still retains its agonized eloquence fifty years later:

Your husband was the most brilliant, able, and inspiring member of my generation. He was the one man to whom this country could confide its destiny with confidence and hope. To have known him and worked with and for him is the most fulfilling experience I have ever had or could imagine. Marian and my weeping children join me in sending you our profoundest love and sympathy.

As transformative as he found life in the White House, Schlesinger’s detour into public service was a sabbatical, not a career change. He had to leave behind a professorship at Harvard University and a multivolume study of Franklin Roosevelt. But as he wrote to Eleanor Roosevelt in March 1961, he could not pass up the opportunity, which would infinitely enrich his understanding as a historian. He worked on Robert F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign in 1968, but after Bobby’s assassination he lost heart in politics and returned full time to the academy. A prolific scholar and public intellectual, he wrote nearly two dozen books, countless essays and op-eds, a massive journal, and, as it turns out, many fascinating letters.

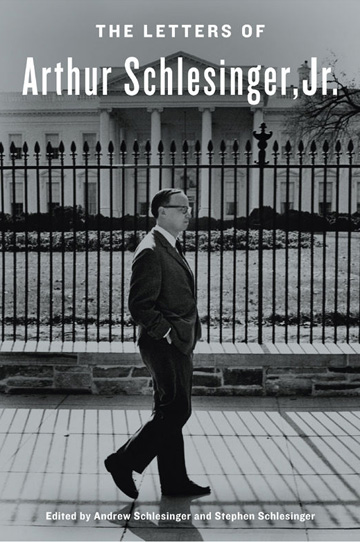

Schlesinger’s collected correspondence, edited by his sons Andrew and Stephen Schlesinger, reveals an unapologetic Kennedy partisan and a champion of American liberalism: a man of the Democratic left but never the far left. As a correspondent, Schlesinger conveys vast learning and impeccable breeding. He was restrained and courtly, lively although rarely funny, touched by glamor if not himself glamorous, firm in support of a principle, controlled even when outraged, frequently pedantic, and always interesting.

The volume contains few entries from 1961-63, when Schlesinger was doubtless too busy to write all but the occasional note. That is just as well, for he said everything that could be said about Kennedy’s presidency elsewhere, especially in the Pulitzer Prize-winning history A Thousand Days, which includes some embarrassingly moist lines: “Underneath the casualness, wit, and idealism, [Kennedy] was taut, concentrated, vibrating with inner tension under iron control,” and so on. But there are letters from the 1960 presidential campaign, and in them Schlesinger proves himself a trenchant and clearheaded adviser. In strong, direct terms, he laments Kennedy’s failure in earlier years to stand up to Joseph McCarthy, and guides him through the treacherous shoals of running for president as a religious minority. He also gives sound tactical advice, directing Kennedy surrogates to refer to the candidate publicly as “Senator” rather than “Jack,” to reinforce his gravitas.

Not all of Schlesinger’s advice rings true. He dissented from Kennedy’s decision to tack to the center against Nixon, urging his man to focus on winning the party’s base of liberal intellectuals, “the kinetic people” who “have traditionally provided the spark in Democratic campaigns.” He gave similar advice in 1984 to Walter Mondale, who followed it, and in 1992 to Bill Clinton, who did not; Mondale lost forty-nine states in the Electoral College and Clinton won two terms as president. Schlesinger can at times appear out of touch with the nuts and bolts of politics. Clearly he counted himself as one of the kinetic people.

He abhorred radicalism. Over the years he engaged in heated disputes with Noam Chomsky, and during the Vietnam War that he so deplored he had no time for “hysterical protest.” When an antiwar organizer invited him to a read-in for peace in 1966, Schlesinger sternly declined, writing, “This problem requires hard and careful analysis; not displays of emotion, however virtuous.” He was also an anti-McCarthyite who happened to be strongly and genuinely anticommunist. As a historian who had observed Joseph Stalin in real time, he could hardly be otherwise. In 1947 he parted ways with Little, Brown and Co. when it refused to publish George Orwell’s Animal Farm, and he spurned the fashions of the academy by denouncing the Cultural Revolution in China and with it Mao’s “infantile leftism.”

One measure of Schlesinger’s value as a political adviser during the 1960s was the bitter enmity he received from his candidates’ opponents. A series of letters in 1960 shows his awkward steps to extricate himself from the camp of Adlai Stevenson in favor of Kennedy. Schlesinger’s services in 1968 were in even higher demand: Eugene McCarthy and Hubert Humphrey both angrily denounced him for choosing Robert Kennedy—and, after Kennedy died, for switching to George McGovern. Humphrey’s letter is the most remarkable document in this collection, a wounded, self-righteous diatribe: “You write history, and I help make it. And, my, how much easier it is to have hindsight than foresight…. I have never been a tag-along. I have been a leader, and you know it. So, in the parlance of the street, knock it off.”

No knight of Camelot can live on ideas alone. He must also have style. Schlesinger was urbane and civilized, and his owlish looks complemented the magazine appeal of the president and his dashing brothers. Alongside speechwriter Ted Sorensen, Schlesinger was known as one of Kennedy’s best and brightest: the thinkers whose credentials and memoranda underpinned the president’s easy confidence. Schlesinger enjoyed full access to the Kennedy lifestyle, with trips to Hyannis Port, sailing holidays, and luncheons among assorted worthies. “The Reinhold Niebuhrs and the Edmund Wilsons will be there,” he promises Gore Vidal in one dinner invitation, name-dropping respectively the most celebrated theologian and literary critic of the day. After a relaxing month on Cape Cod he laments that his “beautiful deep tan is fast giving way to Widener pallor.” Widener, as you know, is Harvard’s main library. Or did you attend some other college?

With this easy superiority, it is little wonder that Schlesinger and his colleagues meshed poorly with Lyndon Johnson, who was a vote counter rather than an idealist. As Robert Caro has brilliantly demonstrated in The Years of Lyndon Johnson, Kennedy’s camp thought the vice president was a hopeless rube and either ignored or underestimated him. In one preposterous letter, Schlesinger advised then Senate Majority Leader Johnson to bring in not one but four economists from Cambridge—two from Harvard and two from MIT—to render him budgetary advice. He soon recognized Johnson’s legislative brilliance but pegged him as “a bully who has made his way in life by leaning on people.” Many letters despair of Johnson’s escalation of the war in Vietnam, but not a one praises his great legislative achievements: Medicare, Medicaid, the Voting Rights Act, or the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that long eluded Kennedy.

As the ’60s gave way to the ’70s and ’80s, Schlesinger focused on his work as a historian, writing a series of books on Nixon’s “imperial presidency,” the cyclical nature of American politics, and the dangers of multiculturalism. He despaired of public developments, describing Gerald Ford as “a man of unchallenged mediocrity” and Jimmy Carter as “humorless, ungenerous, cold-eyed, crafty, rigid, sanctimonious, and possibly vindictive.” Carter’s moralism and religiosity disgusted Schlesinger, and in 1976, for the only time in his life, he did not cast a vote for president. In 1980 he badly misjudged Ronald Reagan as an accommodating lightweight. Handsomely, he admitted his mistake months into Reagan’s presidency.

A running theme in the collection is Schlesinger’s occasionally naive belief that personal relationships can transcend political disagreement. A person who holds this credo must occasionally temper his views, or express them with diplomacy rather than force. Yet Schlesinger had to have his say, and as a consequence many friendships end in these pages. One notable clash begins with a wounded letter from Henry Kissinger, who protests a newspaper article in which Schlesinger trashed him for claiming to have honor. Schlesinger responds by upbraiding Kissinger for placing the words “honor” and “Nixon” in the same sentence—but nevertheless expresses hope for renewed relations. In another set of awkward exchanges, with William F. Buckley Jr., Schlesinger more or less proves the limits of turning off politics at the stroke of cocktail hour. When Buckley asks Schlesinger to blurb one of his novels, Schlesinger clumsily refuses.

His proud association with the Kennedy family sigil ironically created his chief limitation as an actor in the century’s great events. Schlesinger was brilliant and perceptive and made mighty contributions to academic history, but he will be remembered foremost as Kennedy’s man. Whether Kennedy was right or wrong about an issue, you will find Schlesinger fiercely guarding the truncated potential of JFK’s administration and rhapsodizing the enduring dignity of his family. A servant cannot have two masters. But Schlesinger served his well.