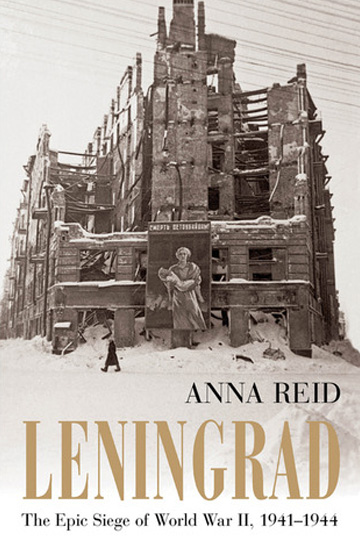

Leningrad

August 30, 2011 | Salon, The Barnes & Noble Review

In September 1941, as the German Wehrmacht sped east toward Leningrad, Josef Stalin struck a blow against sentimentalism in warfare. His advisers told him that the Germans were putting Russian children and elderly at the front line and ordering them to beg the Red Army to surrender the city. Soviet troops recoiled from orders to fire on their most vulnerable countrymen, but Stalin would have none of it. “No sentimentality,” he wrote in a memo to his generals. “Beat the Germans and their creatures, whoever they are. It makes no difference whether they are willing or unwilling enemies. Smash the enemy and his accomplices, sick or healthy, in the teeth.”

During the same month Hitler expressed a similar disgust with the scruples of his own top brass. In June 1941 he had suddenly renounced the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact and invaded the Soviet Union, opening the eastern and decisive front of World War Two. He intended to raze Leningrad and Moscow, expel or exterminate their occupants, and establish a vast settling ground for the German people. An officer protested that killing Leningrad’s inhabitants outright would “let loose a worldwide storm of indignation, which we can’t afford politically.” Hitler unwittingly channeled Stalin by rejecting this “sentimentality.” Permitting himself the liberty of the third person as he invoked the city’s pre-revolutionary name, Hitler wrote, “The Führer is determined to erase the city of Petersburg from the face of the earth.”

Anguished comparisons between the moral depravity of Hitler and Stalin abound, but Uncle Joe occasionally gets a pass when it comes to the Soviets’ famous stand at Leningrad. That chapter in what Russians call the Great Patriotic War remains a solemn source of pride: 800,000 civilians alone starved to death during the 900-day siege, but the city held and the Germans were pushed back. Stalin and communism emerged stronger than ever.

In her devastating book Leningrad, journalist Anna Reid admires the sacrifice and resilience of the Soviet people but challenges the myth—popularized by Brezhnev and inflated by Putin—of “selfless, disciplined heroes” who starved “nobly, in a sort of ecstatic trance.” Assembling a pastiche of newly discovered siege diaries, Reid tells a story of Soviet incompetence and cruelty, and establishes that mass starvation is a nightmare wherever it occurs. While Hitler was unquestionably the aggressor and deserves the most blame, Reid demonstrates that “under a different sort of government the siege’s civilian (and military) death tolls might have been far lower.”

But this book is not an academic argument: it’s a relentless chronicle of suffering. It bypasses the military and strategic aspects of the eastern front to illuminate the experience of civilians. Most of the starvation occurred during the harsh winter of 1941-42 as the Germans surrounded Leningrad and shelled it mercilessly. The Soviet government did not evacuate civilians early enough or protect food stores from the German blitz, and Stalin diverted grain and matériel to fortify Moscow. Cut off from the world, Leningraders ate whatever they could find: first their rations; then their pets; then belts, shoes, pine needles, glue, and motor oil; and eventually each other. Reid’s most remarkable diarist, Dmitri Lazarev, captures the limp tedium of a day spent starving at the office:

We sat round the stove in silence, heads bowed. We sat for hours, not moving, not talking. When there was no more firewood the stove went out. Though there was a big pile of wood in the courtyard nobody had the strength to chop it and carry it up the stairs. Instead we sat out the wait until lunch in the cold. After lunch we went home.

The most striking passages of Leningrad explore Russians’ ambivalence toward their government during the siege. Some bitterly welcomed any respite from Bolshevism—at least until they witnessed the Nazis exterminating Russian Jews, POWs, and civilians. Others felt a surprising surge of patriotism that hardened into resolve in the face of Nazi atrocities. Hitler’s greatest mistake was to underestimate the determination of the Russian people not to be conquered. Yet if anything could dampen their solidarity it was the Soviet purges and terror that continued during the siege. Hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans, kulaks, intellectuals, and minorities were forcibly displaced or sent to the Gulag. Reid excerpts the diary of a soldier who tired of gnawing on horse bones and made an official complaint about ration levels. He was shot for “expressing disappointment at the food supply of the Red Army.”

Leningrad is a major contribution to our understanding of the human side of one of the war’s tragic episodes. Reid missteps only occasionally, as when she quotes passages from Solomon Volkov’s book Testimony, which purports to be the dictated memoirs of the Soviet composer Dmitri Shostakovich, whose Seventh Symphony, “Leningrad,” became a wartime anthem for the city in 1942—but scholars have fatally undermined the authenticity of Volkov’s book. Leningrad is also a grimly relevant book as headlines tell of the famine enforced at gunpoint that currently ravages Somalia. There are no winners when hunger is used as a weapon. There are only survivors.