One struggles to find a concise, representative anecdote about the late David Foster Wallace for an audience of politically minded readers. Wallace, who committed suicide in 2008 at age forty-six, was the most promising and accomplished writer of his generation. An athlete of prolixity, he published a celebrated novel of 1,100 pages called Infinite Jest, several meaty volumes of short stories, a monograph or two, and a pair of essay collections filled with footnotes that had their own footnotes. He tended to avoid prescriptions or answers, instead plumbing the complexity of topics like grammar, tennis, state fairs, and television. He was not especially political.

But he did write a brilliant essay about John McCain for Rolling Stone in 2000. Clever editors at the magazine booked Wallace a press pass on the Straight Talk Express between the New Hampshire and South Carolina Republican primaries; they titled the resulting article “The Weasel, Twelve Monkeys, and the Shrub.” (George W. Bush was the Shrub.) In reclaiming the piece for his 2006 collection, Considerthe Lobster—and returning to it long passages that a “mensch” at the magazine had removed “with sympathy and good humor” during a “radically ablative editorial process”—Wallace renamed it “Up, Simba.” One of the network video cameramen traveling in the bus’s press corps had liked to say that phrase “in a fake-deep bwana voice” as he hoisted his $40,000 rig. The goofy new title was essential Wallace: it at once exploited the funniest anecdote in the piece; broadcast his discomfort with authority and prestige by allying him with the scruffy techies; and made a serious intellectual point: was McCain a regal Simba, or was he regal only by a trick of presentation through the camera lens?

This magazine’s readers answered that question for themselves long ago—if not during the 2000 primaries then certainly during the 2008 general election. Citizen McCain, with his expedient repositioning, ferocious temper, and shameless cashing-in on character-building experiences, made that easy. But in addition to examining McCain, “Up, Simba” also discussed the cultural forces that both produced him and revealed him as a fraud. The key was advertising— one of Wallace’s most animating topics. McCain ran for president in an era of marketing, and his vaunted authenticity itself became a product, with catchphrases like “Telling the truth even when it hurts him politically.” Which, of course, helped him politically. McCain sought, Wallace observed, to reap political gain by affecting indifference to political gain. In the face of this confusing show, one could only feel “a very modern and American type of ambivalence, a sort of interior war between your deep need to believe and your deep belief that the need to believe is bullshit, that there’s nothing left anywhere but sales and salesmen.”

Wallace’s suicide created a lacuna: the guy who wrote in the biggest, boldest type had suddenly silenced himself. His death prompted a publishing drive that is at once soothing and a little unseemly: Wallace’s speeches, stories, and unfinished novels keep popping up smartly packaged in bookstores and in the pages of the New Yorker. This is better and worse than watching home movies of a lost loved one. Better because for most of us, words are all we ever had from Wallace; as long as new ones appear, the illusion lingers that we haven’t lost him. Worse because home movies, unlike handsome new volumes, do not pretend to be anything but dated facsimiles. Nor are they for sale.

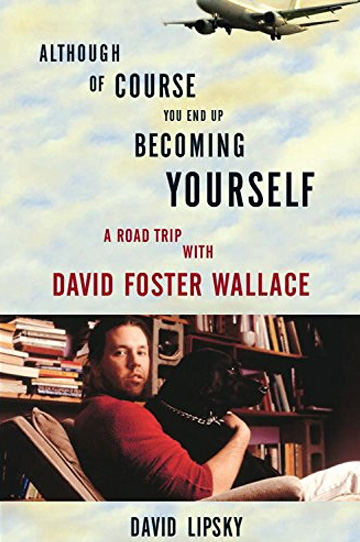

The latest addition to this phenomenon is David Lipsky’s Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, which the publisher describes as a biography of Wallace “in five days.” Put less artfully, it is the edited and stylized transcript of a road trip Lipsky took with Wallace in 1996, during the end of the Infinite Jest book tour. Even though officially Lipsky was the interviewer and Wallace the subject, they became pals, talking about movies, music, craft. Lipsky abashedly admits that he wanted to be liked. His subject was a fun dude, observant, generous, exuberant, hilarious—in short, great company. The reader, hanging out with Wallace vicariously, gets the sense of jogging along with a world-class sprinter. The jogging is very fine.

In his introductory essay, Lipsky, who is a novelist and Rolling Stone reporter, cringes at some of the questions he threw out fourteen years ago. Rightly so. They include many 1) requests to respond to this or that obscure quotation; 2) attempts to pin down the details of Wallace’s storied (and much exaggerated) addictions; and 3) bromides to the effect of, “How does it feel to have arrived?” Lipsky edits out most of his own contributions to the dialogue, which I suppose is fair enough, and also includes material that Wallace asked to be kept off the record, which feels decidedly less so. Yet despite its flaws, Although of Course is a fascinating document and a gift to Wallace’s many fans.

Martin Amis once said that a critic should absent himself as much as possible when discussing a great writer—the goal “is to work your way round to the bits you want to quote.” Wallace’s writing certainly deserves that treatment, but so too, it turns out, does his extemporaneous speech. Here he is, on the road and off the cuff, on whether Infinite Jest is unfilmable:

[Probably, u]nless it’s like one of these forty-eight-hour Warholian, bring-a-catheter-to-the-theater, experimental things.

On fame:

[A] lot of this stuff, it’s nice, I would like to get laid out of it a couple of times, which has not in fact happened. I didn’t get laid on this tour. The thing about fame is interesting, although I would have liked to get laid on the tour and I did not.

On media attention:This machine that has you out here, asking about my reaction to a phenomenon that consists largely of your being out here. Which of course won’t get said in the essay. But, I mean, it’s all very strange.

On breakfast:

I’m not even going to start on the idea of eating a hamburger at 7:00 in the morning. The idea is you eat eggs, which are kind of a latent form, as your body itself is awakening.

On dating as a shy man:

Psychotics, say what you want about them, tend tomakethe first move.

On the pilot’s disturbing announcement about deicing the airplane’s wings:

Is this one of those deals where we have a sudden intuition, andbolt off the plane on the tarmac?

On bathroom etiquette:

You might not want to go in, I just wreaked a little havoc.

It has become a commonplace in the literary community to call Wallace a genius. This seems to occur in part because he won a MacArthur “genius” grant, which many writers covet, and in part because he wrote about math, which many writers fear. Mostly, though, the plaudit stuck because Wallace was smart and articulate and had the enviable quality of finding everything interesting. But in truth, his appeal lies more in his honesty than his intellect; it is less that his observations were profound than that others lacked the self-scrutiny or courage to voice them. Throughout the road trip, Wallace spoke with disarming candor about difficult issues: a suicide scare in college, an almost crippling fear of how others perceived him, difficulty finding love. No contemporary writer discussed despair and loneliness with such frankness.

But at the same time, his writing— especially the beloved essays—is tremendously funny, a thorough index of human quirks and charming insecurities (usually his own). Readers everywhere felt a little less lonely knowing that someone shared them. Wallace tapped into what Lipsky nicely calls the “brain voice”—placing on the page in all its absurd detail what it feels like to live, to observe, to experience. In his most famous essay, “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again,” which first appeared in Harper’s in 1995, Wallace chronicles his time aboard a seven-day Caribbean cruise, beginning with “the shattering, flatulence of-the-gods sound” of the ship’s horn. Staff decline his morbid inquiries about his cabin’s super efficient vacuum toilet, which produces “a concussive suction so awesomely powerful that it’s both scary and strangely comforting—your waste seems less removed than hurled from you.” He details the skilled, unobtrusive professionalism and extreme coolness of his Hungarian wait er, Tibor—“the Tibster”—and confesses, “I sort of love him.” His elderly tablemates at tea dislike Wallace’s tuxedo T-shirt; formal attire is expected. The average young punk would smirk with self-satisfaction at such a gag, but what makes Wallace so loveable is that he is mortified to have given offense. He probably broke out sweating.

And yet in the middle of this riotous stuff are arresting insights. The result of being pampered in every possible way is not the state of pure, transcendent bliss promised in the cruise company’s glossy brochure; it is an unscratchable itch for more. Luxury is like candy: not intrinsically bad, but unsuitable sustenance. Its rewards far exceed its demands.

Joy and sadness: this juxtaposition makes Wallace’s death at once more devastating and less surprising. How could a writer whose prose breathed in life so fully take his own? And yet, as Lipsky observes, suicide “has an event gravity: Eventually, every memory and impression gets tugged in its direction.” Looking back over Wallace’s corpus, you notice plenty of heartbreaking observations and nods to the depression that would ultimately claim his life. We owe it to ourselves not to ignore those—Wallace’s writing illuminates the painful truth that life can be unbearable. But we owe it to him not to let those passages eclipse the vitality that made his prose, and his readers, come alive.