In Search of Lost Dublin

February 23, 2018 | The Wall Street Journal

The other morning, my wife and I arrived early to breakfast. The restaurant had not yet opened so we took a walk, even though the day was cold. Chicago’s West Loop is a supremely fashionable neighborhood but rough at the edges, a remnant of its recent industrial past. Each intersection therefore entailed some question as to whether to turn or continue on. In the end we agreed on which way to go. Both of us were drawn to a block taken up by a striking brick building with a kaleidoscope of doors: yellows and reds, blues and greens, popping brightly against the wet stones. The building seemed splendidly out of place, and as we admired it we realized why. It belonged in Dublin. Add a wrought-iron fence and a pub on the corner and we might have been standing in Merrion Square.

“I am convinced,” writes the Irish novelist John Banville, “that there is a special and unique quality to the bricks of which so much of Georgian Dublin is built.” Ranging from “rosy pink through cadmium yellow,” their “hues alter subtly with each passing hour”—especially when it rains, as it usually does. Mr. Banville’s connection to Dublin dates from the early 1960s, when he moved there from Wexford, a town on the southeast coast of Ireland. But in truth the second city of the British Empire captivated him from childhood, when his family would take the train up for his birthday each December. With the streets decked out in lights, the small boy would get a new wristwatch and his mother and sister would do the Christmas shopping.

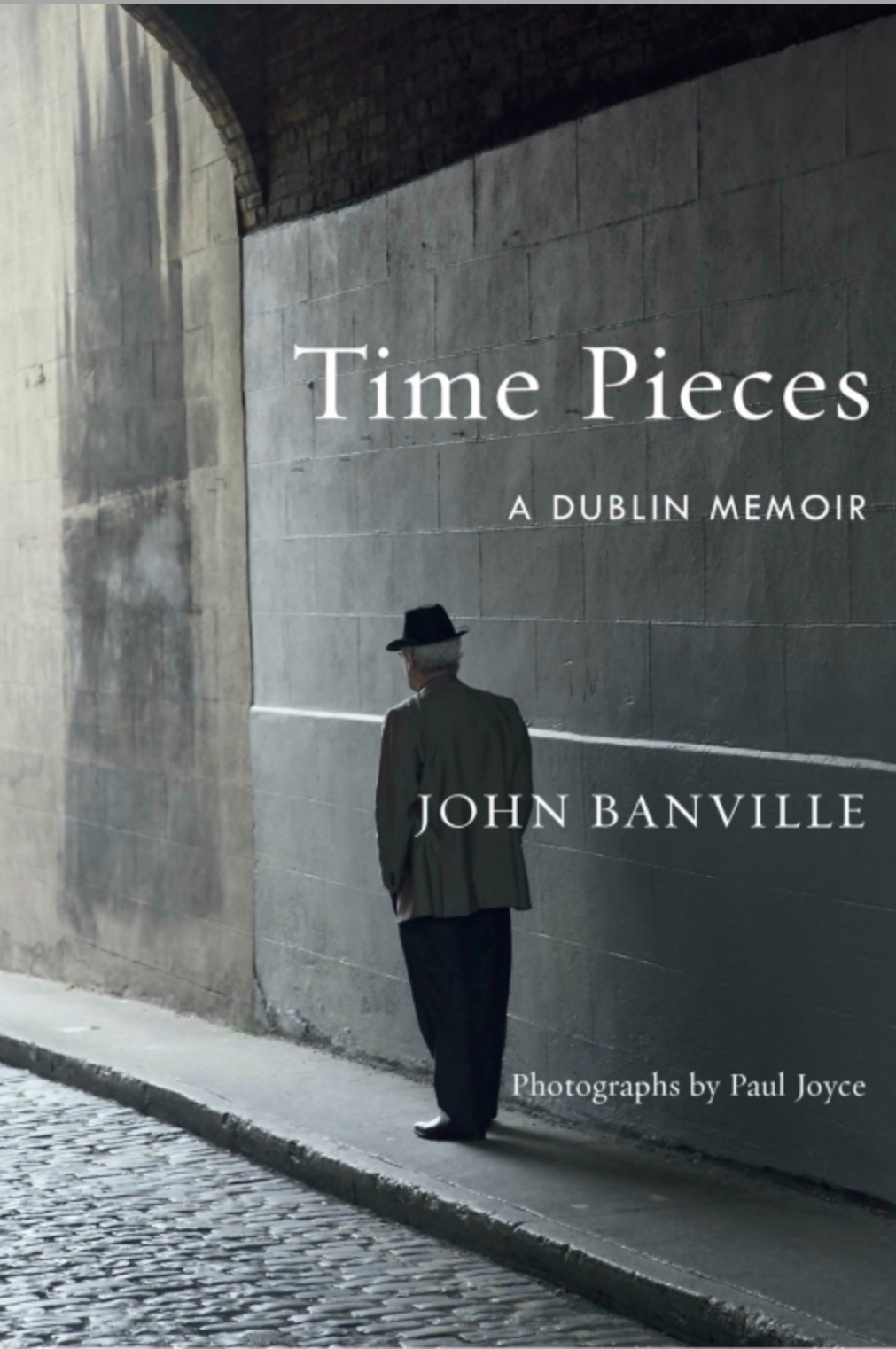

Mr. Banville is not the cliché of a 70-something Irishman, all red-cheeked laughter over pints of stout. His reputation—honed in 16 novels, some fierce literary criticism and a series of delightfully mordant mysteries under the pen name Benjamin Black—tends more to the dour and acerbic. Thus it is a welcome surprise to read his generous and inventive new book, “Time Pieces: A Dublin Memoir,” his best since the Booker Prize-winning “The Sea” (2005). True to form, he begins “Time Pieces” by downplaying the city at midcentury as “mostly a grey and graceless place.” But Mr. Banville’s affection for his adopted home town soon shines through, setting a lovely tone of geographic nostalgia. If Vladimir Nabokov’s “Speak, Memory” showed us the memoir as riddle and Martin Amis’s “Experience” gave us the memoir as history, Mr. Banville has written the memoir as place. “The present is where we live, while the past is where we dream,” he writes. Not quite: In “Time Pieces,” the past is where we go.

All the hallmarks of Dublin appear in this compact and handsomely illustrated volume: Grafton Street, Trinity College and St. Stephen’s Green; sausages, rashers and “vegetables boiled to within an inch of their lives”; tea, Guinness and whiskey (never Scotch); the Liffey; the General Post Office; Yeats, Wilde, Beckett and, most certainly, Joyce; the Abbey Theatre and the Easter Rising—all on cobblestones damp from the Irish rain. Although this book features places and things more than people, Mr. Banville pauses from time to time to word-paint characters in vivid terms. Mrs. Delahaye, his onetime girlfriend’s mother, was “bird-like, with a slight stoop and dyed hair as shinily black and brittle-seeming as shellac”; she “chain-smoked Gitanes—her ‘gaspers,’ as she grimly called them—so that the house smelt throughout like a French bistrot.” And the owner of the best pub in the city, Ryan’s of Parkgate Street, was “Mr. Ryan himself, tall, spare and sandy-haired, with a limp that made him seem to be poling himself along in an invisible gondola.” Mr. Banville writes as if he no longer has anything to prove, only things he wants to remember.

The author is first of all a storyteller, and several of the stories in “Time Pieces” present the many-sided gem of Irish magic. A friend visited Belvedere College, the Jesuit school that James Joyce attended and later commemorated in “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.” The friend mentioned the great novelist to one of the retired teacher priests, who paused a great while, cleared his throat, looked at the ceiling and murmured, “Ah, yes, Joyce. Not one of our successes.” Here are the Catholic Church, the city’s famed literary pedigree and Irish wit all coming together. At other times wit is enough to stand alone. Mr. Banville writes of an old friend who compared himself to the census: “broken down by age, sex and religion.” And he recalls an encounter with a sewer worker who, having startled the author by popping up out of a manhole, instantly put on a wild look and asked, “Is the war over?”

More frequently “Time Pieces” deals in more serious fare. Mr. Banville recounts the morning in 1966 when the concussion of an IRA bomb woke him, and apologizes to a long-gone aunt who died (peacefully) before he could say goodbye. A lovely chapter chronicles a young love, nurtured, as young love so often is—as my own indeed was—by a private corner of a Dublin city park. Mr. Banville celebrates the city’s famous pub culture, but a note of bitterness creeps through when he considers one establishment, favored by writers, “where many a masterpiece was talked into thin air.” For the Church he has mostly harsh words. One censorious priest cruelly ordered his mother to give up her subscription to Woman’s Own magazine, full of harmless articles about the Royal family, knitting patterns and recipes. Of the clergy sex-abuse scandal, he asks in bitter astonishment, “How could we let them get away with it for so long?” But the question contains its own answer: “We let them get away with it. Power is more often surrendered than seized.”

Mr. Banville has his regrets, but seems to regret most that more life is behind him than ahead. Throughout “Time Pieces,” he writes with deep feeling but rarely slips into sentimentality. It is not an easy feat as you survey the past and confront the power of place. I myself paused and sighed as I came across a photo in this book of the Dublin bridge where, some 20 years ago, I first worked up the nerve to kiss the young woman who would become my wife. (The city is gorgeously photographed throughout by Paul Joyce.) Mr. Banville gives himself something of a premature epitaph: “Should have lived more, written less,” he laments. Fair enough. But what he has written here is beautiful.