Exonerating Hitler’s Composer

April 21, 2016 | The Wall Street Journal

Ghosts have always haunted Bayreuth. Years ago, while conducting at the Festival Theater in the central German village, Christian Thielemann occasionally seemed to hear from one. A phone in the orchestra pit would signal an incoming call with a blinking light, catching Mr. Thielemann’s eye. He would pick it up with one hand and continue conducting with the other. “ Herr Wagner says it’s too slow,” he would be told, or “Herr Wagner says it’s too loud.” Sometimes Herr Wagner himself was on the line. Not Richard Wagner, of course, but his intimidating grandson, Wolfgang Wagner, who sternly guarded Bayreuth’s legacy for nearly 60 years. Wolfgang’s credo for the theater his grandfather built was both formidable and pure: “Art reigns here.”

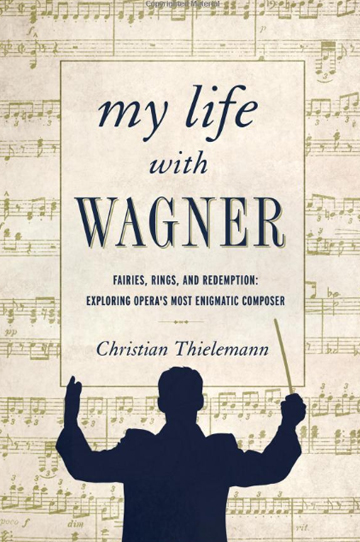

Mr. Thielemann makes that credo his own in “My Life With Wagner.” To him it means not merely putting the music first but also bringing to rest the notion that Wagner’s troubling political history should figure in contemporary artistic conversation. “Once Tristan begins,” he writes, “nothing else matters. Music wins the day.” The music director at Bayreuth since 2015, Mr. Thielemann is an unapologetic admirer of Wagner’s operas, from “ Rienzi” to the “Ring,” finding in them the ultimate source of musical expression.

The author’s penchant for controversy precedes him. In 2000 Mr. Thielemann was obliquely accused of using an anti-Semitic slur against the Israeli conductor Daniel Barenboim, an accusation that he denied. Three years before he had been compelled to defend his decision to present a work by Hans Pfitzner, a Hitler sympathizer, at Covent Garden in London. Last year Mr. Thielemann made provocative comments sympathetic to the far-right Pegida movement, whose leader was recently found guilty by a German court of inciting hatred by calling Muslim asylum seekers “cattle” and “trash.”

It is well that such controversy may bring readers to “My Life With Wagner,” because the book itself won’t. It is a mess. It starts out as a memoir but soon begins to wander. There are discussions of previous Bayreuth conductors and a few stabs at biography. The final 100 pages offer chapters on each of Wagner’s operas, with lengthy plot descriptions and other forms of padding. Throughout, Mr. Thielemann’s brash personality is on display. On the first page he mentions that he has perfect pitch, and on the second he writes, “Fortunately my talent was discovered early.” His rhapsodies to Bayreuth are moist indeed: “It is where I learned to domesticate my heart.” He shows a striking disregard for operatic directors. If they do not read music, he says, “it is pointless to discuss anything with them.” As for singers, if they ruin their voices trying to shout over his orchestra, “it is their own fault.”

Mr. Thielemann describes Wagner’s notorious anti-Semitism and his appropriation by the Nazis, but he believes that the effort to tar Wagner with the swastika is “simple dogma” and “political correctness.” The music must be judged on its own merits, he says. Mr. Thielemann proceeds to make his case with chronology: Wagner died six years before Hitler was born and therefore has an airtight alibi. When asked how he can conduct “Die Meistersinger” in Bayreuth—it was performed there before Hitler and at Nazi Party rallies—Mr. Thielemann blithely writes, “very easily.” He asserts that “it is not an artist’s job to let his view of a work be dictated and distorted by its previous performance history.”

The intersection of art and politics is more complex than Mr. Thielemann acknowledges. Does Shostakovich’s music lack merit because some of it was propaganda made to order for Stalin? Of course not—and of course Wagner’s music does not lack intrinsic value because of its history. Some of it is glorious, like the prelude to “Parsifal.” But this does not mean that avoiding Wagner is mere political correctness to be sneered at like one of Mr. Thielemann’s singers. Wagner wrote the soundtrack to the most loathsome genocidal war machine in human history. On that basis alone his music must always bear an asterisk. Some, like Leonard Bernstein, have championed Wagner’s music while openly grappling with the composer’s scarred past. Others turn away from his music altogether because its associations are too painful. Wagner is not generally performed in Israel. A right-wing German has no business calling this reluctance into question.

That would be the case even if Hitler had appropriated Wagner’s music for ends that were wholly unforeseeable. But they were not. In an essay called “Judaism in Music,” Wagner purported to describe the character of the Jews with words like “repulsive” and “repellent,” referred to them as less than human, and concluded that their curse could be lifted only by their destruction. The Nazis did exactly what Wagner said ought to be done, and the “Ride of the Valkyries” inspired their busy hands. Wagner smeared the reputation of his contemporary Felix Mendelssohn, a prominent Jewish composer whom he hated and envied. The act of character assassination prefigured the Nazis’ own targeting of Jewish artists and intellectuals decades later.

Mr. Thielemann acknowledges these points and says that he regrets them but insists that we let bygones be bygones once the curtain rises. Yet he fatally undercuts his own argument. When discussing the family-like atmosphere of musicians at Bayreuth, he writes that the community must share a personal and artistic sensibility: “What use is an unpleasant bastard to me even if he plays the oboe divinely?” Just so: Humanity trumps art. What use, some may fairly ask of Wagner, is a proto-fascist even if he composed epic operas? Listeners must decide for themselves where to draw that line, and it is no easy task. Ideally they will do so without a popinjay like Mr. Thielemann in their ear.