IN a 1990 essay on Billy the Kid, the Irish writer and critic Fintan O’Toole observed, “For Britain, the Irish are the Indians to the far west, circling the wagons of imperial civilization. Once in America, of course, the Irish cease to be the Indians and become the cowboys. They are the Indian killers and the clearers of the wilderness.” Where does that leave Sir William Johnson, England’s Irish-born emissary to Native Americans during the eighteenth century? Did he play the part of embittered Irishman, once emasculated but now full of swagger in the presence of an even weaker people? Or did he evolve into a proud Englishman, checked only by a familiar fear of unfamiliar savages?

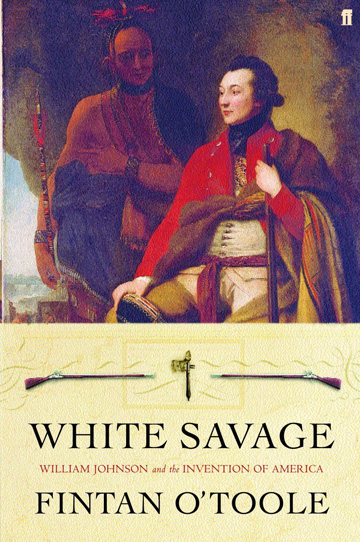

Johnson did neither. As O’Toole shows in his excellent new biography, White Savage: William Johnson and the Invention of America, the Irish colonist was a successful intermediary between England and the Iroquois confederacy. He also became a pragmatic champion of coexistence between whites and natives at a time when clear thinking was in short supply. Johnson’s complex cultural upbringing in County Meath — genteel yet rustic, Catholic at heart but formally Protestant because of discriminatory penal laws — prepared him to bridge two radically different societies skeptical of the other’s motives. Both sides were well-served by his efforts: For Britain he won the Iroquois’ critical loyalty during the French and Indian War from 1754 to 1763, and for the Indians he preserved land, autonomy and dignity for as long as possible.

Young William left Ireland in 1738 at 23 to colonize his uncle’s vast properties in the Mohawk country of what is now upstate New York. He quickly developed a reputation for honesty while trading with local Indians, and when the English, wrestling with the French for control of North America, decided to ally with the Iroquois and needed an ambassador, Johnson was their man. He received a military commission and proved himself indispensable in King George’s War (1744-48) by leading bands of Mohawks on guerrilla-style terror raids into French colonies. He was soon made England’s superintendent of Indian affairs and helped win key battles at Lake George and Ft. Niagara during the French and Indian War. Through his familiarity with and respect for Indian customs — he spoke Mohawk, dressed as an Indian much of the time and expertly conducted ritual ceremonies at enormous multi-nation summits — he persuaded France’s Indian allies to stay on the sidelines, guaranteeing easy victories for the crown.

But England was short-sighted. After winning the war, Johnson’s superiors began resenting the cost of his Boss Tweed-style system of payoffs and gifts to the Iroquois. The new policy was to keep them in thrall by suppression. Meanwhile, other colonists, heedless of the official borders that Johnson had painstakingly negotiated, encroached unchecked onto Iroquois lands and took what they wanted. This betrayal, which embittered Johnson, is an all-too-familiar story in America. O’Toole registers outrage with subtlety, naming the chapter in which the British disingenuously invoked Indian savagery to justify their actions, “Barbarians.”

Much has been written about Johnson, so why another book? For one thing, the standard work, by Milton Hamilton, deals mainly with Johnson’s military career and does not cover the last ten years of his life. For another, no one has explored Johnson’s Irish identity or examined his substantial place in American mythology. O’Toole makes these his primary focus.

On the face of it, Johnson’s loyalty to England was a rejection of his Irish roots. He led a group of white rangers who fought the French mostly out of hatred for Catholics, and he casually converted to Protestantism, lest any fears of popery stand in his ambitious way. He even bought Irish indentured servants, in addition to many slaves. But O’Toole shows that the erstwhile Catholic had Gaelic blood in his veins. His department of Indian affairs was a thoroughly Irish outfit, staffed with relatives and friends from home. After he retired to tend his enormous land holdings, he created something of an Irish feudal town by welcoming Scottish and Irish tenants and organizing raucous St. Patrick’s Day festivals complete with greased-hog chases. The most revealing incident, as O’Toole shrewdly observes from Johnson’s correspondence, was Johnson’s reaction to England’s attempt to label its Indian allies British subjects. The proposal, a mere formality, touched a nerve and he fought it in terms that also encompassed the grievances of generations of subjugated Irish. Perhaps Johnson’s own experience being treated as a savage in Ireland informed how he spoke for the Iroquois.

On Johnson’s legacy and continuing role in the American imagination, O’Toole is similarly perceptive. Though he was a loyal British subject whose heirs fought for the crown from the American Revolution through the War of 1812, Johnson evolved in lore and literature into the archetypal American: a plain-spoken, sensible and physically violent frontiersman. (He was the inspiration for James Fenimore Cooper’s character Natty Bumppo in The Pioneers and Last of the Mohicans.) O’Toole argues that this mythology helped rationalize the federal government’s Indian removal policy in the 1830s. If the noblest aspects of the Indians could be absorbed by versatile whites like Johnson, Americans could crush the natives without sacrificing their contribution to America’s rugged cultural identity.

This book shows that O’Toole deserves his reputation as one of Ireland’s finest writers. The research is impeccable, demonstrating a command of the primary sources and an impressive grasp of topical secondary sources; the writing is graceful and engaging, delivered in a journalist’s column-sized bites; and the analysis is boldly, even jarringly, incisive. No hagiographer, O’Toole examines his subject with an open mind, exposing Johnson’s many faults along with his strengths. The result is a major contribution to our understanding of the centuries-old cross-pollination between America and Ireland.