Eamon de Valera, the father of modern Ireland, was that rarest of political animals: the ascetic diva. He dressed in black and ate sparingly, his face lined and gaunt behind wire-rimmed glasses. One American diplomat observed that, with his “rather stern countenance,” de Valera appeared “to be in perpetual mourning for a nation in bondage.” Yet this severe and severe-looking man had to have things his way. When a delegation failed to seek his blessing before signing the Anglo-Irish treaty with Great Britain in 1921, establishing the Irish Free State, de Valera’s wounded pride helped start a civil war that claimed thousands of lives. In 1932, he became president of Ireland’s executive council after campaigning to reduce ministerial salaries on the slogan, “No man is worth more than a thousand a year.” Except Dev himself, of course, who would receive an even £1,500.

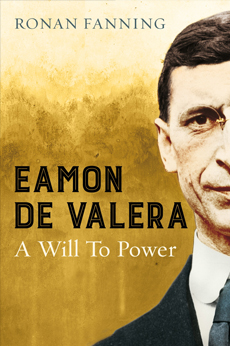

De Valera (1882–1975) is the subject of many biographies, including several authorized productions that he carefully supervised. But “Eamon de Valera: A Will to Power,” by Ronan Fanning, stands out. A historian emeritus at University College Dublin and a frequent commentator on Irish politics, Mr. Fanning shows why de Valera is “incomparably the most eminent of Irish statesmen” while also detailing the ways in which his “lordly and inflexible” manner led him into corners. “A Will to Power” is an astute, nuanced and highly readable life that manages to be both sharply critical and expansive in its judgments. In this era of doorstop biographies, Mr. Fanning deserves extra praise for accomplishing all this in a trim 300 pages.

Mr. Fanning’s subject was an unlikely Irish hero. There was first of all the mystifying name, given as Edward de Valera to a boy born in New York City. His mother was an Irish domestic servant and his father an upper-class Spaniard who died shortly after de Valera’s second birthday. His mother returned him to Ireland and abandoned him. He would eventually replace “Edward” with the Gaelic “Eamon,” scrap his way into a university, and prepare for a career as a professor of mathematics.

Fate intervened in April 1916. The Easter Rising was a failed revolution seeking Irish independence from Britain that nevertheless laid the cornerstone of sovereignty. De Valera found fame not for his political or military accomplishments but for merely being the last man standing: He was the most senior military commander not to be executed. Older and better educated than his fellow soldiers, he marched tall before a column of them in defeat, radiating authority and gaining notice. He inaugurated a century of protest by Irish-nationalist prisoners by leading the young inmates in parade exercises and demanding their recognition as prisoners of war. When the authorities released him in 1917, he learned that the radical party Sinn Féin had chosen him as its candidate for a by-election to Parliament.

“A Will to Power” focuses heavily on the ensuing years, up to 1945, during which de Valera repeatedly gained and lost power and led the drive to redefine Ireland’s relationship to Britain. The civil war, in 1922-23, was his low point; Mr. Fanning’s judgment that he was “in large part responsible” for it is unassailable. When Michael Collins and his fellow delegates signed the 1921 treaty that fell short of complete independence, de Valera rejected it “not because it was a compromise, but because it was not his compromise,” Mr. Fanning writes. Bafflingly, he had established the delegation but then refused to lead it and eventually rejected its work, even after the Irish parliament ratified the treaty. It was the first sign of what proved to be a pattern of anti-democratic obstinacy on de Valera’s part. He linked arms with the Irish Republican Brotherhood—the forerunner of the IRA—and declared that proponents of the treaty would “have to wade through Irish blood.”

The civil war followed, and after that de Valera spent a decade working his way back into power. Once on top again in 1932, his finest hour began. He patiently chipped away at obstacles to Irish sovereignty, consolidating his authority with snap elections and exploiting the British abdication crisis to inch Ireland free of Britain’s grasp. He personally drafted the Irish constitution of 1937—it replaced the constitution of 1922 and established Ireland as an independent state—and he painstakingly revised trade and defense treaties with Britain. World War II proved the ultimate test: De Valera’s determination to remain neutral, Mr. Fanning writes, was an assertion of Ireland’s sovereign right to make its own foreign-policy decisions. But it came at a price. Winston Churchill never forgave de Valera for sitting out the fight, and the United Nations denied Ireland’s membership petition after the war. In his lowest moment, de Valera made the “grotesquely ill judged” decision in May 1945 to underline Ireland’s neutrality by signing the German embassy’s condolence book upon the death of Adolf Hitler.

De Valera’s response to the criticism that followed this monstrosity spoke volumes: “I acted correctly and I feel certain wisely,” he declared. Mr. Fanning writes that this boast may as well have been his epitaph. De Valera’s “impregnable sense of self-righteousness,” and his lifelong habit of disregarding the advice of others, made for an unattractive personality that was prone to tactical error. He heeded his own counsel, whether in moments of existential concern for Ireland or while performing the mundane business of government. He also made one or two ethical decisions of dubious merit, like presiding over a media empire while also serving as prime minister. By the time he left power in 1959, he had made many enemies. From 1959 to 1973 he was president of Ireland, a ceremonial position only.

An American comparison seems appropriate for a figure who was born in the United States and who returned there repeatedly. Eamon de Valera was one part Lincoln and two parts Wilson. Like his contemporary, Woodrow Wilson, de Valera had an infuriating and at times even frightening messianism: He alone knew what was best, and if he did not get his way then the ship would just have to sink. Just as Wilson’s refusal to compromise on the League of Nations ensured its rejection by the Senate, so did de Valera’s obstinacy lead to the Irish civil war. Yet Lincoln shone through in de Valera’s tall, mournful figure, flashes of kindness, and weakness for homely parables. (“Many a heavy fish is caught even with a fine line if the angler is patient.”) More important, the great U.S. president was evident in de Valera’s ability to see through the morass of daily politics to find a straight line to an essential national goal: Irish independence. Without this one man, it might not have happened.

Reconciling de Valera’s pro-and-con column is Mr. Fanning’s task, and he succeeds admirably. De Valera’s success in establishing the Republic of Ireland—officially founded in 1949—may well overshadow all, but this success was bound up in his lonely vision and anti-democratic ways. Sometimes obstinacy is the only way to win in statecraft—just ask Margaret Thatcher. Yet it leaves a sour taste and a mixed legacy. “A Will to Power” shows that even a nation’s greatest heroes have shadows.