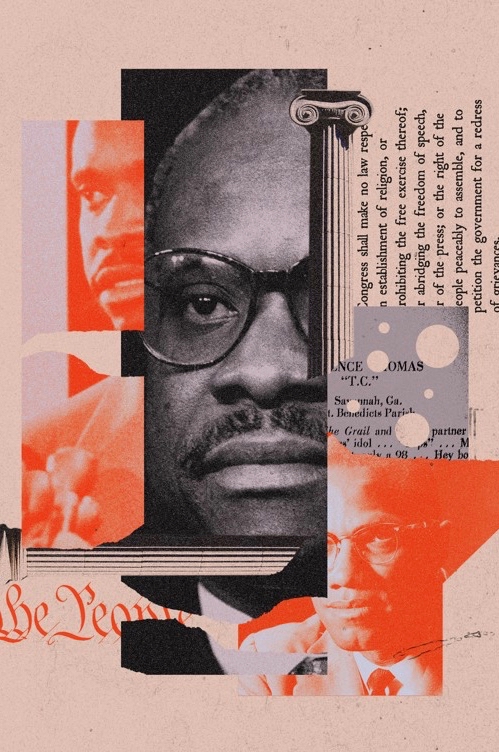

Deconstructing Clarence Thomas

August 5, 2019 | The Atlantic

The first thing to know about Clarence Thomas is that everybody at the Supreme Court loves him. Surprisingly, given his uncompromising public persona and his near-total silence during oral arguments, Thomas cultivates a jovial presence in the building’s austere marble hallways. Unlike most of his colleagues, he learns everyone’s name, from the janitors to each justice’s law clerks. He makes fast friends at work, at ball games, and at car races, and invites people to his chambers, where the conversations last for hours. Thomas’s booming laugh fills the corridors. He passes silly notes on the bench. As the legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin wrote in 2007, with his “effusive good nature,” Thomas is “universally adored.”

This from a man whose career as a judge is a study in brutalism. Thomas is by far the most conservative justice on a very conservative Court. He advances a reactionary legal philosophy that would take America back to the 1930s. That won’t happen: Unwilling to compromise and often unable to attract the vote of a single colleague, Thomas frequently writes only for himself. He also endured the most searing confirmation battle of any modern American public servant, an ordeal that put race, sex, and power in the national spotlight. By all accounts, including his own, the experience nearly destroyed him—not to mention what it did to Anita Hill, who accused him of sexual harassment. Thomas has since nursed a long list of grievances, vowing to “outlive” his critics and writing in his 2007 memoir, My Grandfather’s Son, about a host of antagonists: “posturing zealots,” “sanctimonious whites,” and—of Hill—“my most traitorous adversary.”

Revanchist politics and a list of enemies to rival Arya Stark’s: These things do not pair naturally with bonhomie at the office. Yet such are the contradictions of Clarence Thomas. He is a baffling figure. The nation’s second African-American Supreme Court justice and the successor to Thurgood Marshall, Thomas opposes most policies that seek to combat discrimination or help minorities. He disfavors integration and even seems to resist desegregation. A former black activist and onetime follower of Malcolm X, he champions a criminal-justice system suffused with racism, and has rejected claims of cruel and unusual punishment made by prisoners. Thomas’s most uncomfortable contradiction, though, rests on an abstraction. He is the Supreme Court’s foremost originalist—that is, he purports to interpret the Constitution as the Founders understood it in 1789. Yet how can a black man make such a commitment when the Founders wrote slavery into the Constitution’s very text?

In his provocative new book, The Enigma of Clarence Thomas, Corey Robin, a political scientist at Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center at the City University of New York, seeks to answer this vexing question. Robin’s thesis is that Thomas’s immersion in black nationalism in the 1960s and ’70s profoundly shaped his conservatism. Demands for a black state and a unified black culture don’t figure on his agenda, but he is staunchly dedicated to a separatist position rooted in individual attainment, achievement without assistance from whites, and self-determination in the tradition of Booker T. Washington. He rejects laws and programs designed to help black people, because he views white paternalism and its attendant stigma as the greatest impediment to black advancement. At the heart of Robin’s book is this extraordinary argument: Thomas “sees something of value in the social worlds of slavery and Jim Crow,” not because he endorses bondage “but because he believes that under those regimes African Americans developed virtues of independence and habits of responsibility, practices of self-control and institutions of patriarchal self-help, that enabled them to survive and sometimes flourish.”

On its face, this argument seems almost as offensive as the “Uncle Tom” slurs that Thomas regularly faces. Something of value? At a minimum, Robin’s perspective is vulnerable to the charge of overstatement. Whatever his views, Thomas has said that he became a lawyer “to help my people.” He has fiercely attacked the standing of white pundits who question his commitment to the advancement of African Americans. On the Court, he has forcefully addressed the topic of America’s racist past. For instance, in the 2003 case Virginia v. Black, he wrote a solo dissent to the Court’s decision protecting cross burning under the First Amendment. In Thomas’s view, given its racist connotations and associations with the Ku Klux Klan, cross burning is a “profane” act of racial terrorism that deserves no constitutional protection. Many of his judicial opinions turn on the assertion that his methodology would produce better results for black people than the prevailing liberal orthodoxy. Thomas has written vividly about “the totalitarianism of segregation” and “the dark oppressive cloud of governmentally sanctioned bigotry.” Robin collects and quotes these lines, but they don’t deter him from painting their author as an upside-of-slavery kind of judge.

Still, Robin is not hurling insults. He is deconstructing a sphinx, and his point carries the uncomfortable ring of truth. If Thomas wants to take America back to its founding, that project entails reconciling slavery and the law. Perhaps this simply cannot be done. For his part, Thomas has not tried, interpreting the post–Civil War amendments far more narrowly than other justices. The Enigma of Clarence Thomas therefore deserves credit for attempting to understand the worldview of a jurist who at times can seem almost willfully perverse.

“For every mountain of hardship Thomas cites” from the Jim Crow past, “he has a matching story of overcoming,” Robin writes. “Indeed, the entire point of these mentions of past adversity is to narrate an attendant tale of mastery.” Here Thomas’s dramatic personal narrative takes on relevance. He was raised by his harsh and inflexible grandfather, Myers Anderson, who maintained a middle-class life through ownership of a modest fuel-delivery business. Anderson wouldn’t let Thomas or his brother wear work gloves on the family farm as they cut sugar cane or helped butcher livestock. He never praised the boys or showed them affection. “He feared the evil consequences of idleness,” Thomas wrote in My Grandfather’s Son, “and so made sure that we were too busy to suffer them. In his presence there was no play, no fun, and little laughter.”

Thomas briefly attended seminary but dropped out because of what he felt was the Catholic Church’s indifference to racism. Anderson proceeded to throw him out of the house. Thomas recounts the scene in his memoir, writing of his grandfather: “He’d never accepted any of my excuses for failure, and he wasn’t going to start now. ‘You’ve let me down,’ he said.” Their relationship suffered for years; Anderson refused to attend Thomas’s graduations or wedding. Where others might never have forgiven such slights, Thomas went on to adopt this very rigidity as his own watchword, praising Anderson as “the greatest man I have ever known.”

Small wonder that a jurist who learned at the knee of such a taskmaster would reject leniency for vagrants, mercy for criminals, and even integration measures. Nor does it come as a surprise that Thomas would open a dissenting opinion on affirmative action (which he opposes) with these lines from Frederick Douglass:

What I ask for the negro is not benevolence, not pity, not sympathy, but simply justice. The American people have always been anxious to know what they shall do with us … I have had but one answer from the beginning. Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us. Do nothing with us!

Thomas may not, like his fellow conservatives, believe that the world, or the Constitution, is color-blind. But he advocates a similar result, arguing that the best way forward for African Americans is with a clean slate, rather than clumsy attempts at redress that only add more insidious obstacles to progress.

Robin’s book establishes that Thomas has a serious vision, however quixotic, for the African American community, and that it deserves to be taken in good faith—even if progressives can demolish it on the merits. Robin proceeds to do just this, as he paraphrases Thomas’s libertarian outlook and then pillories it as a fairy tale:

In a market freed of government constraints, extraordinary black men like Myers Anderson will emerge. If Myers could succeed in the market despite Jim Crow, others can do so too. Every bit of reality would suggest that this is a fantasy on Thomas’s part, that the odds are overwhelmingly against African Americans, that the market clearly privileges whites. But that’s how all romance, including capitalism, works: One Cinderella will be chosen, a special someone will succeed, and that will make all the difference.

This magical thinking informs Thomas’s juridical approach, too. As even his admirers acknowledge, Thomas stands alone in making his argument. In his recent and admiring book, Clarence Thomas and the Lost Constitution, the journalist and historian Myron Magnet devotes a chapter to what he considers Thomas’s best opinions as a justice. They are all dissents or concurrences, because Thomas rarely has the chance to write for the Court in politically sensitive cases. Partly this has to do with his exceptionally conservative views, but above all his isolation reflects his disregard for the Court’s precedents. He is willing to abandon whole lines of case law, many of them generations old, and start fresh. Though Thomas’s supporters see him as a constitutional purist writing for the ages, his method reflects a level of antipragmatism that approaches self-sabotage. Adherence to precedent, or stare decisis, is one of the foundational principles of our legal system, promoting stability and order. It is also the way of the world, as elemental to the judiciary as the fact that judges wear robes.

The loneliness of Thomas’s constitutional approach made headlines in another context this past spring, when he filed a concurring opinion in Box v. Planned Parenthood linking early birth-control advocates to the eugenics movement. Multiple scholars highlighted the flaws of his armchair history. Thomas dispensed with any pretense of dispassionately analyzing the Indiana abortion law under review, describing women who seek abortions as “mothers” and drawing a rebuke from Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Once again he wrote only for himself. The opinion displayed Thomas’s long-evident disdain for women, from his legal career back to his origin story as the scion of Anderson, a powerfully self-sufficient patriarch. Thomas has spoken disparagingly of his sister, whom Anderson did not take in, and who was instead raised by an aunt and deprived of the middle-class upbringing and private education that Thomas enjoyed. In the justice’s worldview, Robin writes, “the effects of being raised by a woman versus a man were devastating.” Racial progress crucially depends on “the saving power of black men,” as Robin puts it.

Which leads, inevitably, to Anita Hill. No discussion of Clarence Thomas, least of all in the era of Justice Brett Kavanaugh and the #MeToo movement, can overlook her. Robin devotes only three pages to Hill, citing the reporting of Jill Abramson in New York magazine and Marcia Coyle in The National Law Journal and stating, “If it wasn’t clear to everyone at the time, it’s since become clear that Thomas lied to the Judiciary Committee when he stated that he never sexually harassed Anita Hill. The evidence amassed by investigative journalists over the years is simply too great to claim otherwise.” This is absolutely correct, but the evidence bears repeating. Abramson and Jane Mayer established in their indispensable 1994 book, Strange Justice: The Selling of Clarence Thomas, that Thomas’s behavior toward Hill was part of a pattern, that despite his denials before the Senate he was obsessed with pornography, and that his penchant for extreme, vulgar sex talk was well known among his friends. Strange Justice also reminds us that Hill passed a lie-detector test, while Thomas refused to take one.

When it comes to race, Thomas’s ideas deserve a substantive hearing. But on the topic of sex he has earned no such deference, having forfeited the lectern through misconduct and deceit. The good intentions that underlie his stark vision for African Americans do not extend to his views on women, leaving only a voting record that is consistently hostile to their interests. Presumably the Founders would not object, gender equality having been far from their minds at the Constitutional Convention. That’s good enough for an originalist. The hundreds of millions of women who have lived in the United States in the intervening centuries understandably demand more. Thomas may be an enigma in his approach to racism. On America’s other original sin, sexism, he is just wrong.