Cunning, Vision, and Immense Resolve

January 17, 2011 | The Barnes & Noble Review

Although he is remembered as the first African-American Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall in his day was one hell of a civil rights lawyer. As general counsel to the NAACP from 1938 to 1961 he argued 32 cases before the Supreme Court, winning an astounding 29. These seminal precedents include Smith v. Allwright (1944) (invalidating Texas’s all-white Democratic primary); Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) (outlawing racist real estate covenants); and Brown v. Board of Education (1954) (prohibiting racial discrimination in public schools). Marshall argued 19 more cases at the Court as the nation’s first black Solicitor General, winning 14 of them. With this record he surpasses even John Roberts, the current Chief Justice of the United States and one of the most celebrated appellate lawyers of our time, who argued 39 cases and won 25. And Roberts didn’t have to worry about getting lynched on his way home from court.

If Marshall’s time on the bench eclipses his civil rights advocacy, so too does the long shadow cast by Martin Luther King. Michael Long, the editor of this inspiring collection of Marshall’s early civil rights letters, seeks from the first line of his introductory essay to give the overlooked Marshall his due. Marshall and King, he argues, were twin pillars holding up the modern civil rights movement, equal in stature. Tension nevertheless separated the two giants: Marshall, who committed his life to the rule of law, disapproved of King’s campaign of civil disobedience. In the eyes of posterity, King’s legacy was enhanced by his tragic assassination, whereas Marshall lived out a long decline on the Court, cut off from the black community, beset by health problems, and forced by a conservative majority into the impotence of perpetual dissent.

Marshalling Justice rewinds the tape to reveal Marshall at his best, full of energy, outrage, and savvy as he counseled clients and witnesses, demanded action from Southern authorities, argued with colleagues over tactics and strategy, and kidded around. Here he is in 1941, relishing the treat of cross-examining white witnesses during an Oklahoma trial:

They all became angry at the idea of a Negro pushing them into tight corners and making their lies so obvious. Boy, did I like that—and did the Negroes in the courtroom like it. You can’t imagine what it means to these people down there who have been pushed around for years to know that there is an organization that will help them. They are really ready to do their part now. They are ready for anything.

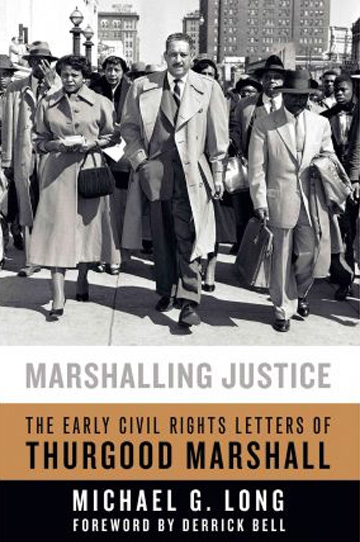

Marshall took on every type of racial injustice, representing black students, soldiers, criminal defendants, homeowners, voters, and ordinary citizens. He challenged businessmen to rename repulsive products like “Whitman’s Pickaninny Peppermints” and “Nigger Head Stove Polish.” He clashed mightily with good ol’ boy editors in the Southern press. One of the book’s most arresting features is the contrast between Marshall’s assured lawyerliness and the near-illiterate letters he received from would-be clients. One senses from the cover photograph on this book the relief they must have felt to have a brilliant, confident champion headed their way: in the picture Marshall strides forward, hand in pocket, legal papers ready, looking anything but afraid.

Part of his job involved countering crass bigotry with cool reason. To the Secretary of War he wrote:

There can be no argument or belief that a white man who is given a transfusion of blood plasma from a Negro thereby becomes a Negro any more so than the injection of horse serum would make a human being become a horse or the injection or snake serum would change a human being into a water moccasin.

Yet if the arguments were easy, the tactics were not. Setting up a successful lawsuit takes planning and skill, and Marshall took pains to establish a perfect record for cases he knew were headed to the Supreme Court. He preserved arguments and made objections to ensure that no wrinkle of procedure or jurisdiction would obstruct the merits. Some of the letters show colleagues harshly editing briefs Marshall had drafted, but these should not be overblown: even the best attorney’s work is challenged and revised, especially when the stakes are high.

The key to Marshall’s success as a lawyer was being just radical enough. On some issues he would not budge: disdaining moderates who tried to make the best of “separate but equal” facilities, he pressed relentlessly for full integration. But he also knew that playing ball was sometimes in the movement’s interests. He stood behind Harry Truman, who waited too long to move on race issues but then moved decisively. He maintained a surprisingly open line with J. Edgar Hoover and cooperated with the FBI’s attempts to root out subversives in the NAACP. (This curious relationship reveals both Marshall’s distrust of communists and his recognition of Hoover as a dangerous enemy. Hoover still spied on him.) He formed a working, but not uncritical, alliance with the Justice Department. Above all, Marshall played the long game, and with cunning, vision, and immense resolve, became one of the twentieth century’s greatest Americans.