People like to call Bill Lerach names. The disgraced plaintiff’s lawyer, who in March will complete his two-year prison sentence for participating in an illegal kickback scheme, has been called a shakedown artist, a carjacker, an economic terrorist, pond scum, even the Anti-christ. In 1995, then Congressman and future SEC Chairman Chris Cox contended that “the only difference between the organized crime of the 1930s and today’s extortion racket run by ‘strike-suit’ lawyers”—of which Lerach was the undisputed king—“is that today’s lawyers’ conduct is technically legal.” To be hit by such a suit—to be accused of fraud or insider trading by a class of investors, and to be exposed to millions of dollars in potential liability—was to be “Lerached,” and every CEO hated it. When, in 1995, over President Bill Clinton’s veto, Congress enacted the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act, or PSLRA, which put new restrictions on the ability to bring class-action lawsuits, everyone called it the “Get Lerach Act.”

Was Lerach an extortionist? Well, did Jesus walk on water? With both questions, it depends on whom you ask. For decades Lerach was a hero on the left, a fearless crusader who protected pensioners and shareholders from corporate fraud. During his thirty years at the legendary plaintiff’s firm Milberg Weiss, the firm returned an astonishing $45 billion in judgments and settlements against the biggest corporations in the world, including Enron, Arthur Andersen, Apple, R. J. Reynolds Tobacco, and Charles Keating’s Lincoln Savings and Loan. Ralph Nader and Senator Carl Levin were among those who petitioned Lerach’s sentencing judge for leniency. (Full disclosure: My law firm, Robinson Curley & Clayton, is involved with a pending securities class action alongside Lerach’s old firm Coughlin Stoia, on which I did some work over a year ago.)

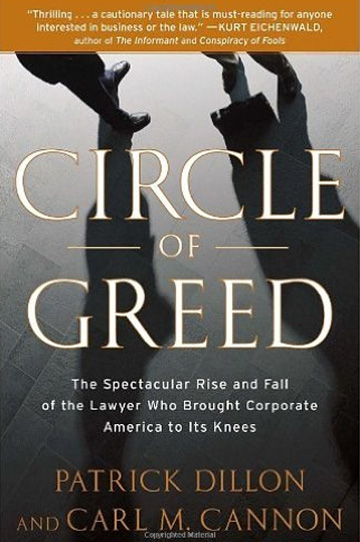

On the other hand, as the subtitle of Patrick Dillon and Carl Cannon’s riveting new book, Circle of Greed, suggests, Lerach was deplored in corporate boardrooms and vilified by the tort reform crowd. He made securities classaction suits part of the cost of doing business in America, and did so with a sneer on his lip. “I don’t give a fuck about the merits,” he once told a startled opponent who balked at his multimillion-dollar settlement demand early in a marginal case. Dillon and Cannon—two scrupulously evenhanded journalists—write that Lerach could be coarse and bullying, and at his worst displayed “vanity, insecurity, impatience, arrogance, and overconfidence.” His enemies also chafed at his selfstyled Robin Hood image—the guy lived in a 17,000-square-foot house and once rented an aircraft carrier for his birthday party. And Robin Hood certainly didn’t own a helicopter or buy Maid Marian bling and furs.

One thing both sides agree on is that Lerach was an exceptionally skilled lawyer, possessing a rare combination of creativity, tactical genius, appetite for risk, and meticulous preparation. Despite his macho image, at heart he was an intellectual, known for writing elegant legal briefs. Milberg Weiss was not some rinky-dink group of ambulance chasers; it was the Cadillac of plaintiff’s law firms, whose attorneys were well credentialed (many of them former assistant U.S. attorneys) and very smart. Lerach, their star lawyer, won a few big judgments in the 1980s and then used his reputation to force major settlements without having to try many cases. Dickie Scruggs, the famous plaintiff’s lawyer who made his fortune in asbestos and tobacco litigation (and who is now in jail for bribing a judge), called this the “three-legged stool” approach of litigation: you only need to saw off one of the three legs to put the defendant on the floor. Some see leveraging settlements as the efficient operation of the legal system; others call it extortion. One frustrated entrepreneur put it this way: “Someone accuses you of fraud. You know with absolute certainty that it’s a lie. You want to fight, but then you find out you really don’t have the opportunity. You’re a dumb businessman if you fight,” because a loss would doom the company. “So you settle.”

Then again, no business settles for tens or hundreds of millions of dollars unless there’s a real chance that a jury would award more in damages—and juries rarely give such awards absent evidence of malfeasance. In any event, it was just as well that from the 1990s on, Lerach conducted most of his business on the phone and in the conference room, because he could rub a jury the wrong way. After a bitter courtroom loss in 1988, he vented in an illadvised memo that jurors were all narrow-minded fatsos. (One does wonder about the populist who despises the people.) He became Milberg Weiss’s West Coast general, managing cases from San Diego and sending troops into court on his behalf.

Milberg Weiss expended huge sums on its contingent-fee lawsuits, investing millions of dollars in attorney hours without the promise of any return. In a fateful decsion that was meant to create a steady new supply of cases for the firm, Lerach made a secret deal to pay Beverly Hills ophthalmologist Steve Cooperman 10 percent of any judgment or settlement Lerach won in a case that Cooperman identified for the firm and served in as head plaintiff. Payments to head plaintiffs in class actions are illegal under the PSLRA, because they dilute the amount of recovery for the rest of the class and usually lead to someone committing perjury.

This scheme allowed Milberg Weiss to dominate the securities class-action market: at one point the firm was filing 60 percent of all such cases in the country. But when Cooperman, a slick, chain bracelet–wearing character, who maintained several rackets at any given time, was caught trying to defraud insurers by staging a theft of two of his own paintings—a Picasso and a Monet—he sang, detailing for astonished investigators the plaintiff-kickback scheme over at Milberg Weiss and thereby shaving off some of his jail time. Lerach copped a plea to a single charge of conspiracy in federal court in exchange for two years’ imprisonment, $8 million in fines, and no obligation to snitch on his partners. Melvyn Weiss, the firm’s legendary chairman, made a similar deal and is also in jail. Lerach, a prominent Democratic supporter who had sued Enron and Halliburton, claimed the prosecution was a witch hunt by the Bush administration, but Dillon and Cannon find no evidence of this. The firm was targeted and brought down by scrupulous career federal prosecutors.

Telling this complex story is a tricky business, but Circle of Greed is up to the task: it is impressively researched and well paced, and offers reporting, not editorializing, leaving the reader to form his or her own judgments. But hints of the authors’ own biases do occasionally peek through. Dillon and Cannon were both clearly charmed by Lerach, sometimes to the point of repeating a little too credulously his version of events. (There is a mawkish scene in which Lerach’s eleven-year-old son eloquently demands an explanation from his father for what he’s been reading in the newspapers; this must have played beautifully with the sentencing judge.) Dillon and Cannon also suggest that even if Lerach went too far, his cause was worthy: “the failures to heed his warnings” about the coming financial meltdown in the late 2000s “came at the expense of every person in this country who owned stocks and bonds and who’d been planning on using them to buy a home, send a kid to college, or to retire.”

Yes and no. The authors’ outrage is understandable, but it is important when discussing these things not to lapse into Lerach’s populist cadences and start measuring out lengths of rope. Lerach was right to predict economic meltdown and to champion those it would hit the hardest, but in his cynicism he was only half right about its cause. To him, the default explanation for a business’s poor performance and subsequent shareholder losses was fraud, and he would just as soon accept a settlement as be persuaded that incompetence or excessive risk taking were really at fault. The current economic mess has undoubtedly revealed illegal pocket lining, but it has brought to light even more imprudence and incompetence. The aggregation of credit default swaps and mortgage-backed securities is not criminal, except in the sense of being so foolish that its effect can be called that. Sometimes a business’s next big thing flops, just as Lerach occasionally tried a case and lost. That doesn’t mean the defense attorney and the judge were in cahoots.

Then again, if the recession has illuminated anything, it is the insufficiency of current financial regulation to protect ordinary investors from the corporate fraud that does exist. This is a leaking hull that plain-tiff’s lawyers like Lerach have undoubtedly patched. In recent years the private bar has recovered far more for investors than the SEC, despite that agency’s mission of enforcing the securities laws.

Conservatives, who purport to favor market-based solutions over government regulation, disingenuously contend that the SEC and not “private attorneys general” like Lerach should keep companies honest, knowing that this would simply mean less oversight. In that spirit the PSLRA represents a pendulum swing in the wrong direction, making it ridiculously difficult to initiate a securities lawsuit even when fraud leaps out from the quarterly statements. Tort-reform bayers also denounce the high pay of the Bill Lerachs of this world, and they are right in identifying something unseemly about the John Edwards “I feel your pain” routine that plays so well with juries. But that pay is a reward for taking great risks on contingent-fee cases, and for beating the best defense lawyers money can buy. Conservatives would probably call Lerach bold and entrepreneurial if he had chased different foes.

Lerach is a classic case of American excess, like the Hummer, the megachurch, Don King, and the Big Gulp. He represents the best and the worst in class-action plaintiff’s lawyers: the idealism and moral outrage on the one hand, and the cynical greed on the other. For that reason it would be a mistake to paint the entire bar with his overreaching. It is also a mistake to use his fall from grace to give a free pass to the defense lawyers he bested. Where are the booklength exposés about the stalling and obstructionist tactics Haley Barbour and Kirsten Gillibrand used while serving as counsel to tobacco companies? The dirty tricks of many big law firms may fall just to the right side of the line that Lerach crossed. But only just.