Ludwig van Beethoven, titan of Romanticism and sublime poet of music, was himself no poem. A misanthrope with a volatile temper and slovenly appearance, he was once mistaken for a tramp and hauled off to spend the night in jail. One of the women who rejected his marriage proposals described him as “ugly and half crazy.” When the king of Prussia sent Beethoven a diamond ring in gratitude for a composition, the surly maestro did not write a thank-you note: he went and had the thing appraised. It turned out to be a fake, and had friends not intervened he would have made a dangerous snub and returned it. Beethoven’s smothering, jealous affection for his nephew and ward, Karl, whom he raised as a son, led the boy to attempt suicide. Karl told the authorities that he did it “because my uncle harassed me so.”

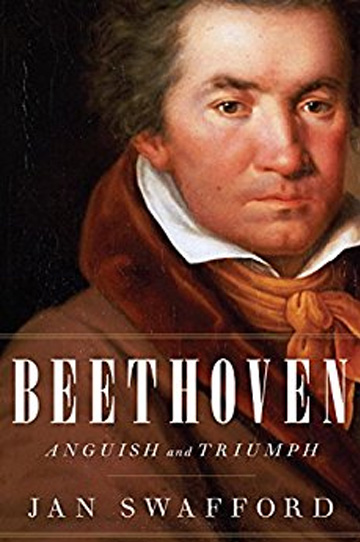

Beethoven “understood people little and liked them less, yet he lived and worked and exhausted himself to exalt humanity,” writes Jan Swafford in his exceptional new biography, Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph. From Karl’s tragedy came one of the most exquisite works in the canon, the String Quartet in C-sharp Minor, Opus 131. Wagner would later call its first movement “the saddest thing ever said in notes.” But Beethoven did not merely transmute personal experience into art; he willed art into being, sometimes from the barest elements. Never as facile with melody as his predecessor Mozart or his contemporary Schubert, he turned trifles like an unremarkable phrase or a banal rhythmic motif into masterpieces. The famous “da-da-da-dum” that opens the Fifth Symphony works this way: the simple motif builds and grows until it reaches gale-force winds.

Swafford, a professor at the Boston Conservatory and himself a noted composer, helps us understand the nature and reach of Beethoven’s genius. Even though he lived during the Age of Revolution — he named his Third Symphony “Eroica” for Napoleon — Beethoven was, according to Swafford, no revolutionary but instead a “radical evolutionary.” He respected traditional musical forms but expanded them: “everything more intense, more poignant, more driven and dramatic, more individual, longer and weightier, with heightened contrasts and greater virtuosity.” The orchestra required for the Ninth Symphony was twice as large as those customary at the time; the piece itself was double the length of standard symphonies. The contrasts between movements in the late piano sonatas are like the peaks and valleys of a mountain range.

Anguish and Triumph is itself a challenging work, although not at all in the same way as Beethoven’s irascibility. Swafford does not deal in jargon — he is a beautiful writer — but he does explore Beethoven’s compositions at length and in detail, illustrating the discussion with extensive musical figures and lingering over concepts like chromaticism and key selection. Readers with some musical background or training will gain the most from his pages. Yet the book is geared toward general readers, and it seems right to ask those who wish to understand one of history’s great strivers to push themselves and grapple with his art. Swafford is a reliable guide, dispensing critical judgments with brisk confidence. (“The Third Piano Concerto is audibly in Mozart’s orbit and safely in his shadow.”) He does not flinch from the many blemishes in his subject’s character but nevertheless approaches him with sympathy and understanding.

Life was hard on Beethoven. He was perennially short of money and chronically ill with maladies that included cirrhosis, gastrointestinal distress, and probably lead poisoning. He desperately wanted love but never found it: his “Immortal Beloved,” who apparently reciprocated his feelings but could not consummate them, remains anonymous to history. He was going deaf. When he realized that he must face life alone and in silence, Beethoven wrote the “Heilingenstadt Testament,” a remarkable document in the nature of an unsent suicide note, vowing to carry on in the name of art. Swafford writes that “to suffer without hope, without believing that suffering has some larger meaning and purpose, requires great courage.” Beethoven — never much of a religious believer — “had something near as much courage as a human being could have.”

His loss of hearing was the supreme trial of his life. It seems unbearably cruel for a musician to lose the one faculty that is essential for the realization of his art. Compounding the tragedy, Beethoven’s hearing disappeared slowly over many years, like a friend walking away over a great expanse. But while deafness devastated him, he came to see it not as a limitation but as another challenge to defy and transcend. As Swafford elegantly writes, “the fact that he could now hear music only in his head is surely what gave some of the late music an inward, ethereal, uncanny aura like nothing else.” It’s hard not to feel awe at a man who could, without ears, hear masterworks. But Beethoven’s real triumph is a matter of humanism rather than art. What should amaze us is not merely his ability to compose in silence but his decision to do so when death beckoned so strongly. As hard as his life was, it was also an ode to joy.