I began counting Ayn Rand’s uses of the word “contempt” on page 43 of The Fountainhead, by which point it had already appeared four times, and twice on that very page. The word shows up thirty-nine times more in the book, by my count, for a total of two score and three. Rand’s villains and heroes smile contemptuously, throw back their heads and laugh contemptuously, and deem others too contemptible to be worth addressing. The most indelible image of contempt takes place when the novel’s hero rapes its heroine in an act performed “in contempt, as a symbol of humiliation and conquest.” If that were all, the scene would not be infamous. But the word reappears several sentences later: “the act of a master taking shameful, contemptuous possession of her was the kind of rapture she had wanted.”

Disturbing as this man-worshipping desire to be raped is—and it is not Rand’s only such scene—the most frequent use of contempt in her fiction is directed not at women but at the public, the masses. As the economist Ludwig von Mises wrote in praise of Rand’s other major novel, Atlas Shrugged, “You have the courage to tell the masses what no politician told them: you are inferior and all the improvements in your conditions which you simply take for granted you owe to the effort of men who are better than you.”

Overuse of this angry word is not Rand’s only literary tic. Her villains and weaklings tend to be fat or effeminate, and she has a fondness for courtroom showdowns. Moreover, critics have so thoroughly savaged her melodramatic, high-camp prose over the years that it seems ungenerous to focus on her writing at the level of the word and the phrase rather than the grand idea. But this particular tic is revealing, for as two new biographies show, Rand herself lived a life of contempt: for people, for ideas, for government, and for the very concept of human kindness. In the most famous (and overheated) denunciation of her work, Whittaker Chambers wrote in National Review that “from almost any page of Atlas Shrugged, a voice can be heard, from painful necessity, commanding: ‘To a gas chamber—go!’ ” The great irony of Rand’s life is that this woman who seemed to despise everyone beneath her became a cheerleader for democratic capitalism, a type of political economy that entrusts the fate of society to the unwashed masses themselves.

Chambers’s hatchet piece—commissioned in an act of malicious mischief by William F. Buckley Jr., who disliked Rand’s godlessness—was particularly cruel considering that Rand was a Russian Jew who had escaped the USSR. But if his language was shockingly harsh, the sentiments were typical of the type of passions Rand inspired during her life, and still inspires today. Although she died in 1982, half a million copies of her books still sell each year, and her followers continue to guard her name like hardball lawyers protecting a trademark.

On the other hand, Rand has never been taken seriously by the literary establishment or the academy, earning sneers when she has gotten any attention at all. But if liberals disdained her, many conservatives feared her ferocious atheism and her quixotic defense of capitalism. Whereas traditional conservatives believe that free markets create the most wealth for all, Rand praised capitalism in moral terms: great achievers have a right not to be held back, she grimly argued, her dramatic cape atwirl and her gold dollar brooch shining.

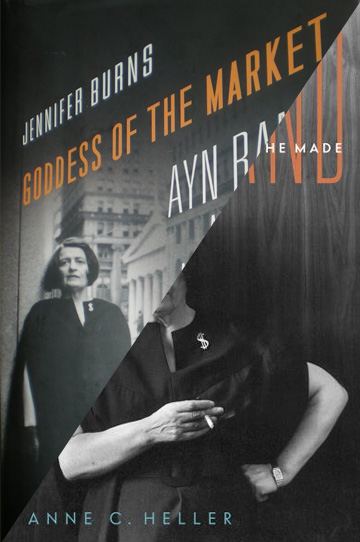

Helping to sort out these competing passions are Jennifer Burns’s Goddess of the Market and Anne Heller’s Ayn Rand and the World She Made, two outstanding biographies that reveal much about a figure who to this point has been chronicled only by biased disciples. The books are pleasantly complementary. Burns’s is an intellectual biography that situates Rand in the tradition of modern lib-ertarian politics; the writing is focused and concise, and the analysis very sharp. Remarkably, this shrewd, accessible work is a doctoral thesis repackaged. Heller’s book is a more traditional life, a detailed portrait that uses a narrower lens, painstakingly but elegantly showing Rand’s descent into intellectual madness. Reading the two books together provides for the first time a complete picture of Rand’s life and works—and the picture is an ugly one.

Both authors contend that Rand’s early years in Russia heavily influenced her intellectual development. She was born Alisa Rosenbaum three weeks after the 1905 revolution, and lived through the 1917 ones and their bloody, impoverished aftermaths. Each author seizes on a different formative experience, and if this type of armchair psychology by biographers is never very reliable, it is in this case certainly plausible. Heller describes an incident in which Rand’s mother paternalistically tricked Rand into giving away a favorite toy. Burns, by contrast, opens her book with a harrowing scene in 1918 when a twelve-year-old Rand watched armed Red Guards forcefully take over her father’s pharmacy for the greater good of the people. Both incidents taught young Rand that tyrants often profess benevolent motives to justify coercive acts.

Rand’s philosophy—developed after emigrating alone at twenty-one to the U.S., scraping by as a screenwriter in Hollywood—was essentially an anti-altruism. She called it Objectivism. No kind gesture on behalf of others should be trusted, because it might disguise nefarious motives. (To Rand, Robin Hood is the ultimate villain.) Selfishness is a virtue; reason, above all, prevails; and emo-tion is inconsequential. Thus Rand believed taxation was immoral, charity was foolish, and equality a terrible ideal; conscription and anti-abortion laws were unconscionable intrusions into citizens’ personal rights. Above all she believed in markets, regulated by little more than courts to enforce contract and property law. Viewing Rand’s uncompromising politics in light of her upbringing in the Soviet Union turns her into a type of Clarence Thomas figure: someone who rebels so strongly against injustice experienced during childhood that she creates an extreme perversion of the usual lessons learned. Whereas Thomas reacted to boyhood racism by voting, from his perch on the Supreme Court, to eliminate any law that purported to help blacks or other minorities, Rand took from communism that no one should try to help anyone else, ever.

But as Rand’s fame grew during her years as a famous novelist, pop philosopher, and elephant-gun for Republican candidates, she tended to ignore the many selfless people who had helped her succeed. There was her family in Russia who sold their jewelry to send her to America; her relatives in Chicago who helped get her to Hollywood; and her many friends whom she soaked for ideas in late-night debates and then disowned irreversibly when they committed heresies like praising Kant or Plato. (Rand preferred Aristotle.) Above all, Heller shows, there was her husband, Frank O’Connor, a patient soul whose idyllic life as a gentleman farmer was uprooted when Rand insisted they move from their ranch in California to New York so that she could pursue her writing. O’Connor pined to return to the ranch for the rest of his life, but Rand, scrubbing the historical record like the communists she so detested, insisted that “he loves New York. He hated California.”

Rand’s greatest cruelty to her ever-loyal husband was to sit him down and explain to him that she would begin carrying on an affair with her intellectual soulmate, Nathaniel Branden. Branden had by that time become the leader of a cult following that surrounded Rand and eventually isolated her from the public in the 1960s and ’70s. Ironically for a group devoted to individualism, they denounced wayward thinkers in Stalinish show trials and lined up to copy Rand’s most prosaic choices (such as her selection of furniture styles). By Rand’s thinking, the affair with Branden was perfectly rational, and emotion needn’t enter into the equation. That was little consolation for O’Connor, cuckolded in twice-weekly trysts in his own bed—nor, as it turned out, for Rand herself, when Branden abandoned her for a younger woman. She denounced him completely in the pages of her newsletter, The Objectivist, and made her followers swear not to attend his lectures. Burns’s book only hints at the full extent of these twisted love triangles and loyalty oaths, while Heller reveals them for the historical record in all their sordid glory.

Burns has the edge, though, in identifying Rand’s intellectual legacy. She describes Rand as “the ultimate gateway drug to life on the right,” elaborating: “Just as Rand had provided businessmen with a set of ideas that met their need to feel righteous and honorable in their professional lives, she gave young people a philosophical system that met their deep need for order and certainty.” Who needs difficult questions, gray areas, and doubt when one can have all of life’s questions conclusively answered in 1,000 easy-to-read pages? And who wouldn’t want to have every base, selfish motive validated by an unassailable philosophy proving that kindness and altruism are actually bad?

Burns also traces Rand’s prickly relationship to the Republican Party: she campaigned for Wendell Willkie in 1940 and Barry Goldwater in 1964 but grew exasperated with the party’s growing religiosity and tepid defense of capitalism. She loathed Ronald Reagan. When the Libertarian Party took off in the early 1970s, one might have expected her to get involved, but instead she flashed her property-rights fangs, insisting that its leaders were stealing her ideas.

Ultimately, both books show that Rand’s own life disproved her carefully wrought philosophy of selfishness. She happily accepted help from others while denouncing altruistic kindness. She trumpeted the virtue of reason over emotion, then surrendered to jealousy of a former lover. More bizarrely, she proved the preposterousness of absolute selfreliance by setting herself up as psychotherapist to many vulnerable members of her salon, doing untold damage to psyches and relationships. Too many young Ayn Rand followers have relied on her novels alone to prove the value of an individualism so extreme that it does not merely ignore others, but actually spits in their faces. Now that biographers have shown the devastation she brought upon those around her, the lesson is painfully clear: behold the ruins of a completely selfish life.