A Faculty for Espionage

October 25, 2024 | The Wall Street Journal

The United States entered World War II with an intelligence deficit. Its allies and enemies had long-established clandestine operations, some of them dating back centuries. But the Americans had no dedicated spy service and relied primarily on military intelligence to gather information about the world. In 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt therefore directed the prominent lawyer William Donovan to form what became known as the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency. Donovan looked for a fresh approach, giving analysis as much weight as fieldwork and building a civilian rather than military operation. Where could he find professionals who were up to the job?

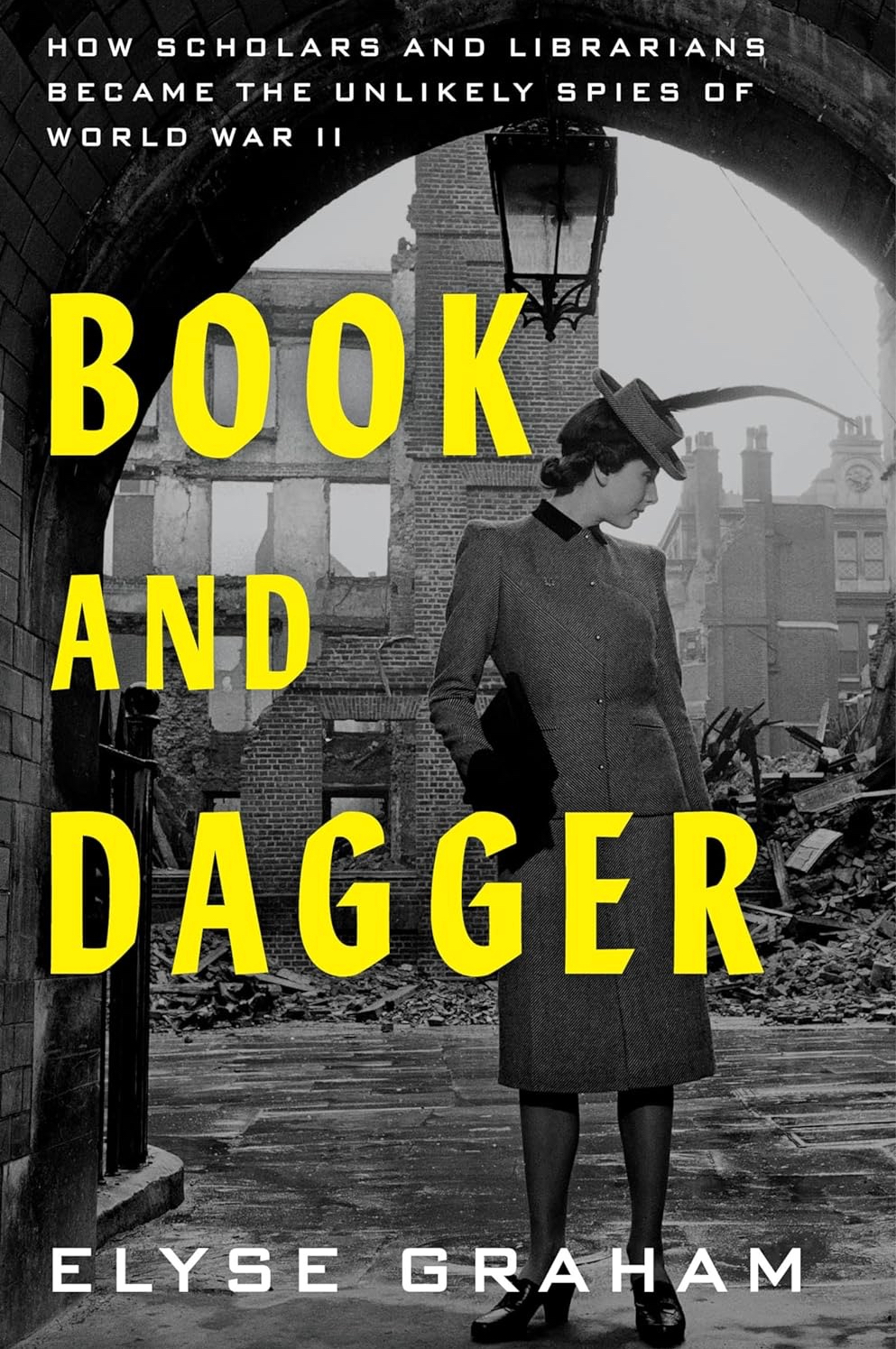

A fascinating new study, Book and Dagger by the historian Elyse Graham, follows Donovan into the unlikely corridors of university faculties as he searched for talent. The connection between the academy and the Manhattan Project is well known, yet the OSS drew not from physics departments but from the humanities. Professors and archivists were natural intelligence officers: adept learners, highly specialized, used to painstaking work and nondescript enough to blend in easily. (As CIA Director William Colby would later say, far from looking like James Bond, the ideal agent has a hard time flagging down a waiter.) As Ms. Graham writes, scholars were rousted “out of their carrels” to form the infant service’s “first full-scale network of professional spies.” Donovan and his colleagues chose “the world’s least glamorous people for the world’s most glamorous profession.”

Book and Dagger tells the story of four such recruits—and surveys many others—with an almost breathless sense of wartime romance and drama. It makes for entertaining, atmospheric reading. “Imagine,” Ms. Graham writes, “the world of bookshelves, the smell of old paper, and the sense of expectation that haunts any labyrinth of texts.” The birth of American intelligence was less about foggy piers and dead drops, she suggests, than the relentless hunt for information, done out of sight and generally without thanks. Her book offers delayed gratitude: “It’s time to remember the scholars and bookworms who helped to win the war.”

All four of Ms. Graham’s principal subjects worked for elite universities when government agents showed up to request their help. Joseph Curtiss, mild-mannered and self-effacing, taught English at Yale. Adele Kibre was a medievalist at the University of Chicago with a gift for getting into the restricted section of archives, including the Vatican’s. Carleton Coon taught anthropology at Harvard and “fantasized about becoming a gentleman adventurer.” Sherman Kent was affiliated with Yale’s history department, though he boasted some field-ready abilities: Once handed a knife he proved able to throw it with dead-true aim.

The OSS trained its new recruits in subterfuge, cryptology, misdirection and combat. As Ms. Graham explains, for the polite scholars “the hard part was not the fighting itself, but learning to ignore the decency” that inhibited them from hitting below the belt or exploiting an opponent’s weakness. One combat instructor favored the “kick to the fork” and made no apologies about putting an adversary on the ground in this ungentlemanly way. One recruit recalled: “Within fifteen seconds I came to realize my private parts were in constant jeopardy” around the ruthless teacher.

The agents were then sent into the field. The OSS’s cover story for Curtiss and Kibre was an assignment to collect books for domestic libraries. This took Curtiss to Istanbul and Kibre to Stockholm. In reality, Curtiss was instructed to develop a counterintelligence program in the crossroads city crawling with Axis spies. Kibre received an assignment closer to her cover story, digging through libraries and bookstores in neutral countries for useful materials the that the Nazis had suppressed from publication elsewhere, such as underground newspapers, technical journals, photographs and maps.

Someone needed to analyze the mountains of data that agents like Kibre produced. Here was Kent’s forte; known as “the father of intelligence analysis,” Kent led the OSS’s Research & Analysis efforts for North Africa and Europe. Prior to the Normandy invasion, Kent’s group pinpointed the location of French airfields, electric stations, railroad crossings and telegraph offices to help forestall the enemy’s use of such infrastructure. They found suitable buildings where the Allies could quickly set up quarters and field hospitals. Using maps and business directories, Kent’s division located the ball-bearing factories in occupied Europe to facilitate Allied sabotage of that key component of Axis weapons manufacture.

After the war, these agents re-entered the academy, with varying degrees of success. Curtiss returned to a quiet life at Yale, which like other top universities became a pipeline for gifted students to enter the intelligence field. (Robert De Niro’s excellent 2006 film The Good Shepherd dramatizes this process with a subplot about a poetry professor luring a student played by Matt Damon into the world of espionage). Kibre resumed her work as a research archivist. Coon—who had been little use during the war, his best idea being to hide bombs in mule droppings—disgraced himself by promulgating racist anthropological theories that were discredited in the postwar years.

The knife-wielding Kent unsurprisingly has the best postscript. After a few wayward years attempting to pick up his life in academia, he joined the newly formed CIA and founded its in-house journal, Studies in Intelligence. He later caused an uproar in 1951 by leading an academic team seeking to demonstrate that the American order of battle could largely be discerned from publicly available sources in Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library. They even went so far as to prove the point in a 600-page report. President Truman himself had to step in to quell the ensuing furor. The message from the government to the academy was clear: Some of you are too clever for your own good.