Band of Sisters

April 15, 2021 | The Economist

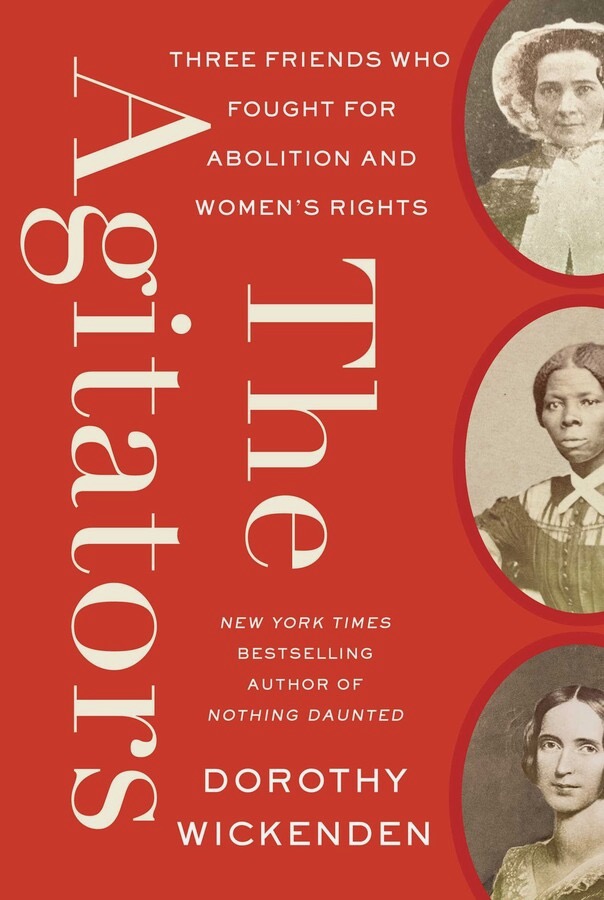

Abraham Lincoln had his team of rivals, but they were all white men with high opinions of themselves. Female alliances also worked to end slavery and perfect the union in 19th-century America. In “The Agitators” Dorothy Wickenden of the New Yorker profiles three neighbours who sought women’s rights and freedom for African-Americans. They banded together at a time when society mistrusted female activists. A newspaper published a letter calling one of their gatherings a “tabernacle of mischief and fanaticism.”

Even for the time, that was an overreaction. As Ms Wickenden shows, the trio’s success depended on middle-class respectability. Martha Coffin Wright, a Quaker and mother of six, found her voice writing anti-slavery essays for the North Star, an abolitionist paper published by Frederick Douglass. Her friend Frances Seward was married to William, governor of New York and a future secretary of state. With a pinched smile she entertained southern grandees and their charming wives. Mindful of his career prospects, William watched Frances’s social agitation with concern, once forbidding her from publicly supporting a school for black students.

The third member of the group is the best known, and the most radical. Harriet Tubman, hailed as Moses, led hundreds of slaves north to freedom along the underground railroad. Her face may soon adorn the $20 bill, according to a spokesperson for Joe Biden’s administration. Tubman found allies in Wright and Seward, both of whom volunteered their homes in upstate New York as underground-railroad stops. “Women, underrated as a matter of course, were less likely to fall under suspicion,” Ms Wickenden writes. The three became friends and comrades.

But the civil war scattered them. Tubman went to South Carolina to establish a settlement for freed slaves and serve as a Union scout and spy. Seward spent time in Washington as the discontented wife of a cabinet member. Her household and Wright’s sent offspring to fight; both mothers anxiously awaited news of their fates. Yet in a quiet testament to her convictions, Wright told her son that he should die before helping return a slave to the South. So that Tubman could continue her indispensable work, Seward became a godmother of sorts to her ten-year-old niece.

Somewhat miraculously, the war claimed just one life in this network of families. The Seward and Wright boys completed their service safely; Tubman would live until 1913. But on the night of Lincoln’s assassination, a co-conspirator came for his secretary of state as well, grievously injuring William Seward and other members of the household. Yet it was not William but Frances who perished. Physically unscathed, she never recovered from the shock of the event and died two months later. “Our calamities do not make us unmindful of the great loss our country has sustained in the death of our good president,” she wrote before the end.

By devoting ample space to family life, Ms Wickenden shows how domestic concerns both defined and constrained 19th-century women. Her subjects loved and wanted the best for their children, but were expected to range no further. Wright chafed at these limitations, as did Seward, whose activism created marital tension (particularly when her husband positioned himself as a moderate in the pre-war years). Yet neither Seward nor Wright went as far as their sometime collaborators Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, whose single-mindedness in pursuit of women’s equality eclipsed all else.

The book’s weakness is conceptual. Including Tubman in the circle of friends will no doubt broaden this volume’s readership, but in every way she stands apart from her allies. Her risks and achievements so outweigh those of Seward and Wright as to place her on a different plane entirely. She belongs in the pantheon of the greatest Americans, not among genteel letter-writers sleeping warmly in their beds. Still, as Ms Wickenden observes, even Moses needed an entourage.