Saint, Sinner, Troublemaker

April 17, 2020 | The Wall Street Journal

In the early 1950s, as the Cold War began to take shape, the radical Catholic Dorothy Day protested a series of nuclear air-raid drills in New York City. Rather than staying indoors as ordered, Day and other pacifists gathered in parks and waited to be arrested. The gesture signified their refusal to participate in “psychological warfare” as well as their penance for America’s nuclear attacks on Japan in 1945. The midcentury drills look quaint in hindsight, a relic of a black-and-white era safely behind us. Yet as a pandemic upends the globe, we are reminded that disaster can and does strike, and that civil preparation means the difference between life and death. One thing we can safely assume: If Day had a second chance, she would skip the drills all over again.

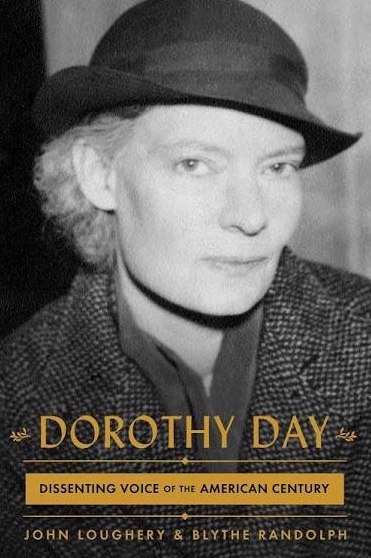

The novelist Saul Bellow might have had Day in mind when he described a character in “The Adventures of Augie March” as “an autocrat, hard-shelled and Jesuitical, a pouncy old hawk of a Bolshevik.” Dorothy Day (1897–1980) was equal parts Mother Jones and Mother Teresa, her white hair pulled back, her gaze level and hard, and her lips pressed together until they erupted in laughter. She had a flat, Midwestern accent for a New Yorker, perhaps from time spent in Chicago and central Illinois. The founder of the Catholic Worker, a left-wing periodical, Day was a Christian first and an activist second. No target was safe, not even the church. In 1948 she cheered on the grave diggers of Calvary Cemetery in Queens during their strike against St. Patrick’s Cathedral. As John Loughery and Blythe Randolph write in “Dorothy Day: Dissenting Voice of the American Century,” “there is enough in the record of her dramatic life to alienate anyone.”

It is the first full biography in nearly 40 years of an icon who may yet become a saint. (The canonization process is under way.) The authors are sympathetic yet clear-eyed in their assessment of Day’s turbulent life and maddening contradictions. “To her critics on the left, she was a distressingly loyal daughter of a reactionary Church,” they write, “but to her critics on the right, she was a rudely outspoken woman of questionable orthodoxy.” She ran a series of soup kitchens and lived among the city’s destitute; Evelyn Waugh described her as an “ascetic who wants all of us to be poor.” Her first miracle, one mourner later remarked, was to grant a morning free of hangovers to everyone who got drunk at her wake.

This was a nod to Day’s bohemian youth. As Mr. Loughery and Ms. Randolph recount, Day lived flamboyantly in the 1920s. During the golden era of Greenwich Village, she drank with Eugene O’Neill and caroused with John Dos Passos and Katherine Anne Porter; she was jailed and brutalized after a hunger strike for women’s suffrage; she traveled to Mexico City and met Diego Rivera. Day also enjoyed many lovers, had an abortion, made several suicide attempts and bore a child out of wedlock. In later life she did not like to hear tell of her glory days.

The authors interweave these dramatic set-pieces with quieter, pivotal encounters between a young Day and everyday religious figures, such as a fellow student who regularly attended Mass at a nearby church. When Day wanted her infant daughter baptized but had no husband, she came across a nun who was willing to facilitate the holy rite. And a kindly priest hired her to serve as a live-in cook at a novitiate on Staten Island, gently guiding her theological reading. He also encouraged her fledgling writing career: “ ‘Have you sold your play yet?’ he would whisper hopefully from his side of the grille after Dorothy’s confession.”

Mr. Loughery and Ms. Randolph are effective scene-setters, but this cinematic portrayal of church life seems rather gauzy. They glance quickly over potentially darker figures that Day later sheltered at her Catholic residences, like priests whose alcoholism or sexual histories “made them unsuitable for their parishes.” This leads to a significant gap in Day’s life story. The book fails to grapple with her response to the signal catastrophe of the Catholic Church in the 20th century: the clergy sex-abuse scandal. The fault may lie with Day herself, who is known to have destroyed many of her personal papers. It is inconceivable that so prominent a figure in the church for so many of the years in which priests serially abused children knew nothing. What did she do about it?

Of course, being a Catholic activist doesn’t make one responsible for solving the church’s most intractable problem. And the scandal didn’t explode into public view until after she died. But by blasting sanctimony from a bullhorn on topics as diverse as nuclear nonproliferation, race relations, imperialism and poverty, Day forfeits a free pass here. Clergy sex abuse rends the spiritual, ethical, moral and social fabric of Catholic life; it is the ultimate test of values for church members. We can’t assume that Day was on the right side of the issue—she often let dogma overwhelm principle. She was disappointingly tepid when it came to the church’s shameful anti-Semitism during World War II. She would brook no criticism of any pope. She called homosexuality “that most loathsome of sins” and fiercely opposed contraception—even when doing so led her own daughter to have nine children during a ruinous marriage.

These contradictions were not, Mr. Loughery and Ms. Randolph write, contradictory so far as Day was concerned. Her values were Catholic values, informed by Scripture and modeled after the teachings of Christ. She broadcast them in her column for the Catholic Worker and during speaking tours—skipping past universities with ROTC programs. Meanwhile the FBI kept tabs on her, particularly when she visited Cuba, and the health inspector tried to shut her soup kitchens down. Occasionally she had to grovel to the cardinal to stay on the right side of the church hierarchy. She was an anarchist—“but only,” the authors note wryly, “if her word was law.” This engagingly written biography illuminates a figure who infuriated as many as she inspired.

Perhaps the most perceptive comment about Dorothy Day was made by her lifelong friend Stanley Vishnewski. The definition of a martyr, he joked, was someone who had to live with a saint.