No One Said It Would Be Easy

May 17, 2019 | The Wall Street Journal

As talk of impeachment fills the air, an exceptionally topical new book explores the failed effort to remove President Andrew Johnson from office in 1868. Johnson ascended to the presidency after Lincoln’s assassination and embarked on a perverse campaign to roll back the Union’s achievements during the Civil War. Racist mobs marauded unchecked through the South, killing African Americans. Factions debated the terms of readmission for states that had seceded. Basic issues about citizenship, the right to vote, and the direction of the country lay open to question. Amid this turmoil, Johnson articulated a crabbed and unworkable vision for the future: “This is a country for white men,” he declared, “and, by God, as long as I am president it shall be a government for white men.”

Most fatefully Johnson, a Tennessee Democrat who had run on the National Union ticket with the Republican Lincoln, would veto important pieces of reconstruction legislation passed by the Republican Congress. When Congress overrode his vetoes, he refused to execute the laws. Eventually congressional Republicans impeached Johnson but failed by a single vote to convict him in the Senate.

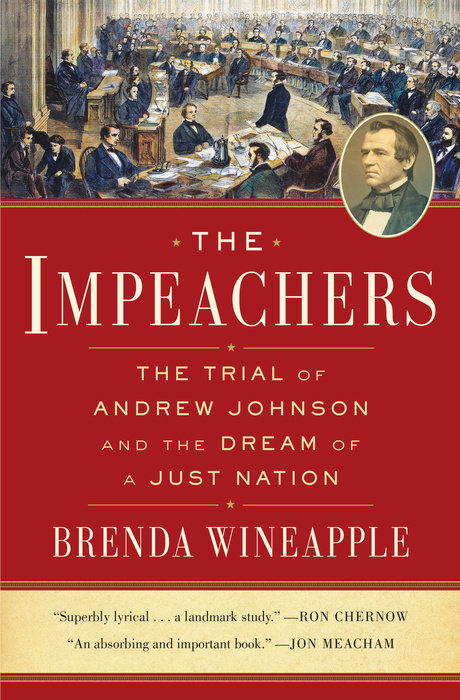

The historian Brenda Wineapple does not once mention our current impeachment debate in The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation. But everything about her book—from its title to the miraculous timing of its publication—suggests the importance of historical reflection at this fraught moment. Its appearance seems to offer a lesson: Before taking sides on whether Congress should impeach Donald Trump, consider what that process meant at another significant moment in our history. Impeachment, Ms. Wineapple writes, is “the democratic equivalent of regicide,” implying “a failure of government of the people to function, and leaders to lead.” Only two presidents—Johnson and Bill Clinton—have been impeached, and neither was removed from office. (Richard Nixon resigned under a threat of impeachment in 1974.) Before impeachment became a ready tool of politics in the past 50 years, its infrequency made it more like a taboo.

The first lesson to draw from The Impeachers is the importance of stakes. They could not have been higher during Johnson’s presidency. “In 1868,” Ms. Wineapple writes, “the situation was far more serious, the consequences more far-reaching, than those of Richard Nixon’s bungled burglary or of Clinton’s peccadillos. The country had been broken apart, men and women lay dead.” Southern states began to pass black codes that denied African Americans the right to vote or own property. Lincoln’s visionary leadership and genius for compromise were replaced by a political vacuum.

Into it stepped Andrew Johnson, a former tailor with no formal schooling; a man who once used a political opponent’s hat for his spittoon; a demagogue who arrived drunk at his own vice-presidential inauguration and openly pined for the murder of his foes. Johnson, a son of the South, had demonstrated true courage barnstorming Tennessee in 1861 giving speeches in favor of the Union. He also held the distinction of being the only senator from a state that seceded to remain in the U.S. Senate. The South never forgave him for this, despite the revanchist program he brought to the White House.

As president, Johnson tallied up an unenviable record of vetoes overridden. The Freedmen’s Bureau Act, the Civil Rights Act and four Reconstruction Acts all passed into law over his formal objection. He then tried to prevent their enforcement. The Reconstruction Acts empowered military governors to take charge and restore order in the South; Johnson directed these forces to stand aside in favor of the civilian governments. He inflamed tensions with racist hate speech. In a telling rejection of the era’s most noble ideals, he made a particular target of the 14th Amendment, which would eventually grant citizenship and equal protection to black Americans.

Johnson’s refusal to compromise with Republicans in Congress confounded those around him. William Tecumseh Sherman compared him to King Lear, “roaring at the wild storm, bareheaded and helpless.” But Johnson believed he was holding the line for the white workers of the land. “He offered his stubbornness as evidence that he was a man of principle when, in fact, he was simply afraid to be wrong,” the historian Annette Gordon-Reed would write.

Ms. Wineapple likewise faults Johnson’s character, perceiving a martyr complex and even an eagerness for the ordeal of impeachment: “The man had a penchant for martyrdom. It allowed him to cling to his belief that he was cruelly beset, deeply unappreciated, wholly persecuted, and denied the respect he rightfully deserved.” This is not an entirely convincing judgment, and seems shaded to draw a parallel with our current president. Historian Eric Foner, in his indispensable study “Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877,” suggests that Johnson was no martyr: He simply miscalculated. After Republicans won super-majorities in the 1866 midterm elections, the impeachment process began.

This book’s strongest feature, Ms. Wineapple’s gift for portraiture, is on display as she sets out her cast of characters. She quotes contemporaries as she sketches the likes of Benjamin Wade, the president pro tempore of the Senate, who stood to inherit the presidency if Johnson were to be removed. (There was no vice president; the rules for vice presidential succession were not established until the 25th Amendment took effect in 1967). One journalist said that Sen. Wade possessed “a certain bulldog obduracy truly masterful,” while Southerners decried him as “that vicious old agrarian.”The author also reminds readers of Thaddeus Stevens, the great Radical Republican congressman whom Lincoln once described as having a bleak face that was always “set Zionward.” One of Johnson’s defenders, New York Republican William Evarts, was cold and calculating—“an economist of morals,” in Henry Adams’s words. And who can forget Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock: “Hancock the Superb.”

The Republicans had a strong moral case, and could fairly argue the president was frustrating the will of the people. But they made a tactical blunder by latching onto a technicality. Then as now, the question arose: If a president may be impeached only for treason, bribery or other high crimes or misdemeanors, must he actually have broken the law in order for Congress to trigger the process? Rather than resolve this knotty constitutional problem, Congress seized on a transgression whose illegality was hardly certain: Johnson’s firing of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Johnson had not consulted Congress before dismissing Stanton in February 1868; at the time this violated the Tenure of Office Act, which required congressional approval for such decisions.

That law was, arguably, an unconstitutional infringement on the separation of powers, and Congress would later repeal it. But it gave Republicans in the House their toehold, and eight of their eleven articles of impeachment concerned Stanton’s removal. Abolitionist Wendell Phillips cried foul: “My wish to impeach [Johnson] tonight is not technical, but because the man, by either his conscience or perverseness had set himself up systematically to save the South from the verdict of the war, and the necessity of the epoch in which we live.” He envisioned a political basis for impeachment, rather than a legal one.

Politics would, in any case, soon engulf the process. Chief Justice Salmon Chase, who presided over the trial in the Senate, had presidential aspirations of his own, and proceeded accordingly. Gradually, moderate Republicans would come to realize that removing Johnson near the end of his term was less wise than simply waiting until November and directly electing Ulysses S. Grant, their party’s popular standard-bearer. The House voted to impeach and the case moved to the Senate for trial.

Those proceedings take up nearly a third of Ms. Wineapple’s book. But where Washington expected a riveting drama, with printed tickets in high demand, what it got instead was a snoozer that bogged down in procedure. It was the nation’s first impeachment trial of a president. What were the rules of evidence? What was the standard of proof? The chief justice, the senators who sat in judgment, the defense and the prosecution had to wing it. Their histrionics occasionally provided relief from the tedium, as when the defense sought a continuance of 40 days to prepare. “Forty days,” cried lead prosecutor Benjamin Butler in objection, “as long as it took God to destroy the world by a flood!” At the trial’s conclusion Johnson was acquitted by a single vote.

Washington descended into claims of bad faith and congressional investigations, and charges of corruption followed the seven Republicans who voted to acquit, especially Kansas Sen. Edmund Ross. “There goes the rascal to get his pay,” muttered one colleague as Ross rushed to the White House after the vote—and indeed, Ross later extracted an unseemly number of patronage appointments from Johnson. The Radical Republicans who had led the impeachment charge saw their position weakened. Johnson, who had no base of support in either party, finished out his term and returned to Tennessee, later finding redemption as a U.S. senator.

What can his impeachment teach us today? Perhaps less about the law than about politics. Fatefully, the Tenure of Office Act was a sideshow that became the main event. Johnson should have been impeached not for violating it, but for impeding Reconstruction. By allowing the debate to proceed on such narrow terms, the impeachers lost the initiative. A hint for future impeachers: Don’t dodge a tricky issue (whether impeachment requires an illegal act) if it means derailing your case.

The broader question from Johnson’s impeachment is whether it was a mistake. Many historians have concluded that it was, no doubt partly due to its incompetent execution. Ms. Wineapple joins a group of historians who disagree. “It had not succeeded, but it had worked,” she concludes. Impeachment served its purpose by undermining Johnson as he debased the nation’s most cherished principles during its weakest hour. There is much to recommend Ms. Wineapple’s argument. “The impeachers,” she writes, “had reduced the seventeenth President to a shadow—a shadow President; that is, a President who did not cast a long shadow.” Scholars of Reconstruction might feel differently about the length of Johnson’s shadow, but his case does suggest that it is possible to constrain a president through impeachment without removing him.