At Her Zenith

December 30, 2015 | Chicago Tribune

At the French palace at Fontainebleau in June 1984, Margaret Thatcher told nine European heads of state that she wanted Britain’s money back. The United Kingdom’s contribution to the European Community was excessive, she said, and always had been. She wanted a rebate. Thatcher’s demand tested the patience of French President Francois Mitterrand and German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who formed an alliance against her. Yet she left the meeting with a 66 percent rebate on Britain’s European contribution. One diplomat observed that “her ability to master the detail and sustain the fight for so long in a ten-sided battle in which she had no reliable friends was astonishing.” As Thatcher’s official biographer, Charles Moore, puts it, “She was the superior of all her counterparts in knowledge, argumentative skill, force of personality and perhaps even in raw intelligence, though not in diplomatic finesse.”

The rebate offers the quintessential Margaret Thatcher story. It contains a bit of exaggeration. Sixty-six percent sounds impressive, but diplomatic papers reveal that it was actually the lowest figure Britain was prepared to accept, diminishing the victory. The story also entails an achievement of questionable merit; the episode after all widened the rift between Britain and the continent. Above all, Fontainebleau forces you to put aside substance and simply admire the raw power of a figure able to face down a roomful of opponents — many of them oozing chauvinism.

Strident, uncompromising, heartless, a bully — all these words have been flung at the woman who became known as the Iron Lady. Yet she was just the bully the old boys’ club needed. The men of Whitehall smirked as Thatcher entered the smoky room of national politics, and before they knew it she had them by the throats. She would assert her will over her country as completely as any modern politician. An episode of the puppet satire “Spitting Image” had her at dinner with her all-male cabinet. She ordered a raw steak. The waitress asked, “And the vegetables?” Thatcher replied, “Oh, they’ll have the same as me.”

Moore suggests in the second of his three- volume life of Thatcher that her dominant style reflected the sexism of the day. She once told the wife of one of her advisers, “if a woman takes on a battle, she has to win.” Moore writes, “She believed men would close ranks against a woman: every inch had to be fought for.” And fight she did. Thatcher was to politics what bazookas are to war.

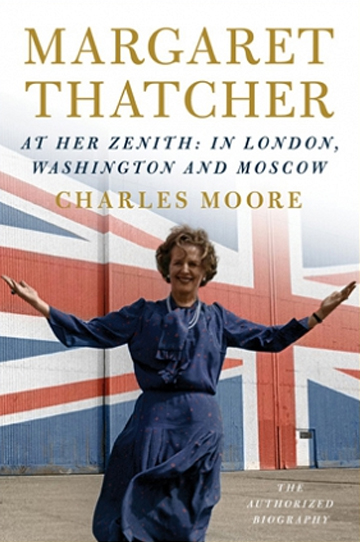

“From Grantham to the Falklands,” Moore’s first volume, traced Thatcher’s youth and ascent to power. “At Her Zenith: In London, Washington and Moscow” picks up the story in mid-1982, covers her best years as prime minister and ends with her final, chaotic re-election in 1987. Moore’s biography is a superb achievement: an authoritative, readable, humane account that reveals some disagreement with Thatcher’s policies but also a thoroughgoing effort to understand her perspective. It is just the right point of view for approaching a polarizing figure.

Like her ideological soul mate, Ronald Reagan, Thatcher viewed her country in terms that were romantic, patriotic and binary. Upon meeting Mikhail Gorbachev, one of her first remarks was allegedly, “I hate communism.” Moore speaks of her “grand simplicities” and observes, “Thatcherism was more like a vision than a doctrine. She carried in her head a picture of her country derived from its past greatness and energetically projected on to its future.” During the “Zenith” years, this vision entailed privatizing national industries, crushing labor unions, promoting Britain’s commercial interests and cultivating its alliance with the United States. Although Thatcher is a conservative icon, some of her reforms seem tame by American standards, such as the dissolution of national behemoths like British Airways and British Gas. Similarly, Thatcher’s showdown with the coal mining unions — the most riveting chapter in the book — seems less reactionary when considering that the unions called a nationwide energy strike in the middle of winter.

Many of Thatcher’s policies nevertheless look no better today than they did at the time. She defied Queen and Commonwealth by refusing to apply sanctions to apartheid South Africa. Moore quotes a shocking memorandum in which she suggested solving the troubles in Northern Ireland by relocating disaffected Catholics: “After all, she said, the Irish were used to large scale movements of population.” One of Thatcher’s key tax reforms was essentially a poll tax, a regressive measure that ultimately helped topple her government. She shrank the state, abandoning the communitarian spirit of postwar Britain and leaving marginal members of society to fend for themselves.

Despite her overwhelming self-assurance in public, Thatcher agonized over decisions behind closed doors. Moore writes that she displayed a “congenital anxiety to understand the detail of everything,” especially scientific or technical matters. Although ruthless to her cabinet ministers, she could be warm to her personal staff, gossiping and fussing. Refreshingly, Moore relays several anecdotes showing that she was not judgmental toward individuals in the midst of personal crisis. When one young MP confessed to her that he was gay, her response was, “There, dear . . . That must have been very hard to say.”

Thatcher’s imperious public style would nevertheless be her undoing. Long-running tensions with her foreign minister and chancellor led to their resignations, and the Conservative Party lost confidence in Thatcher herself. But the lady was not for turning. During a session of Prime Minister’s Questions in her last year in office, she was as combative as ever, telling one MP that she had “the same contempt for his socialist policies as the people of East Europe.” It is possible to disagree with Margaret Thatcher and still find her magnificent. The next volume of Moore’s outstanding biography will be the last. It is sure to be a treat.