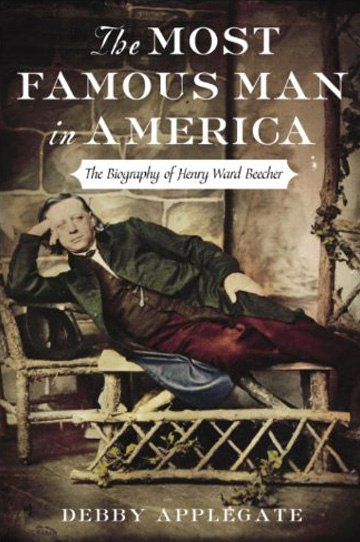

Modern readers will recognize the name Henry Ward Beecher, if at all, as the brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose 1852 novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” helped precipitate the Civil War. But as the title of Debby Applegate’s biography, “The Most Famous Man in America,” screamingly makes clear, in his day Henry was the better-known Beecher. Iconoclastic preacher; friend to Twain, Whitman and Emerson; naturalist; libertine; sometime abolitionist; scoundrel — he wore all titles lightly, coasting on charisma. While he sat in court, accused of seducing his best friend’s wife, he happily sniffed a nosegay of violets.

Like his contemporary, the radical abolitionist John Brown, Beecher was raised by a hard-preaching father. Lyman Beecher was “the last great Puritan minister in America,” an orthodox Calvinist whose crushing injunctions about original sin and eternal hellfire cowed little Henry into a stuttering wreck. Your ordinary Catholic and Jewish guilts don’t even come close. But where Brown used paternal fire to forge steel, Beecher toasted marshmallows. He was a ham, not a visionary; he goofed off for the girls and cut up with the boys well into adulthood. His legacy is not bold anti-slavery work but helping redirect church doctrine to emphasize Christ’s unconditional love rather than the terrifying isolation of sin.

Beecher attended seminary and then served as a minister through the 1830s and ’40s in Presbyterian churches in Indiana. With his theatrical preaching, moderate anti-slavery views and irreverent style, he caught the attention of Eastern abolitionists who needed a leader for the new Plymouth Congregational Church in Brooklyn, which was conceived as a progressive alternative to politically and doctrinally conservative Presbyterianism. Beecher made his fame there and on the lecture circuit as a preacher (but never really a pastor), drawing huge crowds as the nation’s most dynamic speaker in an era without television, radio or respectable theater.

His enthusiasm for the anti-slavery cause ebbed and flowed with the tide of popular sentiment, starting with his support for free-soil settlers who fought to keep slavery out of “bleeding Kansas” in the 1850s. He raised money to ship them rifles — quickly dubbed “Beecher’s bibles” — and built Plymouth Church into a center of anti-slavery activism and a rumored Underground Railroad stop. When John Frémont ran in 1856 as the Republican Party’s first presidential candidate, Beecher joined the campaign and wrote much of the party’s anti-slavery platform himself. (His main job on the stump: to reassure voters of Frémont’s Protestant bona fides after nativists accused the candidate of closet Catholicism.) But as the Civil War approached, he backpedaled on slavery, saying that it should be left alone in the South. He loudly called for emancipation in the early 1860s, but after the war he was a Pollyanna, a staunch Andrew Johnson supporter who argued that the Confederate states would come around on their own without strong Reconstruction measures.

And then there were the ladies. Applegate chronicles Beecher’s three known extramarital affairs, one of which probably produced an illegitimate child. Another, with Elizabeth Tilton, led to ruin. Her husband, Theodore, had been Beecher’s admiring assistant and then his co-editor at the prominent New York newspaper the Independent, which Beecher used as an editorial perch. The two men became intimate friends, but Theodore was gradually alienated by his mentor’s moderate political views as well as rumors of his philandering.

No one knows for sure if Beecher and Elizabeth Tilton actually had sex — they both denied it, although she later recanted — but the nation was scandalized when the story got out and Theodore sued for “criminal conversation” in 1874. Evidence is the backbone of litigation, and piles of anguished correspondence between the three — letters of understanding, tripartite agreements and other memorializations imprudently retained by those trying to keep the secret — filled the docket and the papers. Beecher’s unfaithfulness was juicy enough on its own, but the real draw for many repressed Victorians was peering inside the Tiltons’ stormy marriage. A hung jury, nine to three in Beecher’s favor, exonerated him, but he never recovered his reputation.

There is much to dislike about Beecher, yet Applegate paints a sympathetic but balanced portrait of him. She admires his huge appetite for talking with everyone about everything, which allowed him to bring practical learning to the pulpit and connect with ordinary people. And she reminds us that like Bill Clinton, Beecher retains a legacy beyond personal scandal. Applegate’s narrative is engaging and well paced, although it dwells too long on Beecher’s childhood and at times could provide more analysis, particularly on the reasons for his inconsistent politics. On the trial itself, it does not surpass Richard Fox’s excellent “Trials of Intimacy,” but of all the books on Beecher, “The Most Famous Man in America” is the most comprehensive, going all the way down to the notes the preacher made in the margins of his books. If only he’d marked up his copy of “The Scarlet Letter” a little more.