The Ordeal of the Presidency

May 23, 2016 | The Barnes & Noble Review

During the early 2000s, a friend and I liked to discuss George W. Bush’s motives. Neither of us were fans of his presidency, but my friend would occasionally defend President Bush — or perhaps try to understand him — by contending that he did not seem like an evil man out to destroy the country. He actually seemed nice: goofy and chummy and quick with a nickname; in short, a bro. The point was worth making, since much of the Left’s criticism of the Bush administration painted him, and especially his vice president, as wicked villains bent on doing wrong. My response to this was to agree that the caricature was absurd: Bush was doing his best during difficult times. But I also argued that a president needn’t be wicked in order to be a failure. He need only be inept.

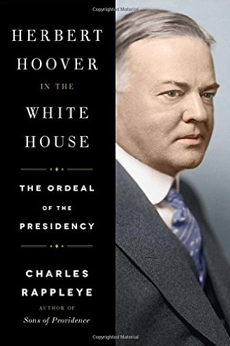

A new book about Herbert Hoover raises this question anew. Hoover’s presidency was abysmal, ranking near the disastrous terms of James Buchanan and Andrew Johnson at the bottom of the Pennsylvania Avenue shuffleboard. (If history places Bush in the company of those presidents, it will have been unkind indeed.) Yet Charles Rappleye, the author of Herbert Hoover in the White House: The Ordeal of the Presidency, essentially makes the same point about Hoover that my friend made about Bush. He was doing his best. The critics went too far. If we truly wish to understand Hoover’s presidency, Rappleye writes, we must put aside caricature and try to get inside the man’s head.

Rappleye makes this point while nevertheless delivering a cold-eyed and indeed harsh assessment of Hoover’s performance in office. His presidency was “shadowed by crisis, frustration, and disappointment,” Rappleye writes. As the 1920s gave way to the ’30s and the stock market crash turned into the Great Depression, Hoover downplayed the nation’s agony, retreated into a dogmatic crouch, and refused to act. “Those who looked to the president for direction got only Hoover’s starched white collar, terse homilies, and petty procedural announcements,” Rappleye writes. “To a suffering, wounded people, the White House appeared distant and implacable.”

Hoover displayed dreadful judgment. One of his most passionate causes was to deny combat veterans an increase in benefits. When it came to Depression relief, he insisted that private charity, funneled through the Red Cross, was sufficient to answer the enormous needs of the citizenry. He kept up this line even as a historic drought added insult to the injury of the stock market crash. Rappleye also quotes a White House interview conducted on background in 1931 in which Hoover displayed shocking callousness toward his fellow citizens. “Nobody is starving,” the president blithely asserted. “The hoboes are better fed than they ever were before.” Describing the so-called Depression as mere hysteria, Hoover declared, “What the country needs is a good big laugh. If someone could get off a good joke every ten days I think our troubles would be over in two months.”

Hapless, wrongheaded, stingy, and weak, yes — but malevolent? Rappleye insists not. While damning Hoover’s actions, he tries to understand where they come from. For instance, Rappleye suggests that the president downplayed the Depression’s effect on regular people in order to shape rather than reflect events. Consumer confidence is a delicate creature, easily spooked; Hoover reasoned that projecting confidence was one way to keep panic in check. He resisted direct government aid out of a firmly held belief that it would lead to a European-style welfare state. And Hoover’s famously strained relations with the press were a product of his formality and reserve. He could not bear the give-and-take of a White House press conference. Simple insecurity also played a part: upon becoming president, Hoover modified his handshake, extending his hand “well forward so that those he greets are held at quite a distance.”

Whether all this is persuasive is one question; whether it matters is another. Well intentioned or not, the verdict remains that Herbert Hoover was a terrible president. What the Depression needed was a bold and confident leader, willing to act, unafraid to gamble, and able to recognize an existential threat to the nation: in a name, Franklin Roosevelt. Yet Rappleye’s book succeeds precisely because he tries to grapple with his man without excusing his failures. Caricature is the enemy of nuance, and nuance is the key to historical understanding. No president has faced such a thorough psychological assessment since Hoover’s fellow Quaker, Richard Nixon. (Incidentally, Hoover, like Nixon, hated the press and sponsored break-ins against his political enemies.)

If Bush and Hoover both failed with the best of intentions, do any of our current presidential contenders approach the office with mixed motives? The easiest answer to this question is to point to Donald Trump’s candidacy, which seems to have begun as a publicity stunt designed to sell steaks and resort packages. Yet Hoover’s presidency teaches us as much about the value of pragmatism as motive. Hoover had no idea that the nation would fall into the economic abyss on his watch. What the presidency demanded from 1928 to 1932 — and what it did not have — was a leader free of ideological rigidity who could respond to events. In this sense, our current presidential contest may have vanquished the candidates most temperamentally resembling Hoover: Ted Cruz and Bernie Sanders have been the notable ideologues of the 2016. campaign. Perhaps that clears the way for the pragmatism necessary to face the challenges that loom: If another calamity as severe as the Depression strikes the country in the next four years, here’s hoping the winner responds with more flexibility than Herbert Hoover. “Nobody’s starving” is not going to play well on Twitter.