By His Own Rules

July 6, 2009 | The Barnes & Noble Review

Few will be surprised to learn that Donald Rumsfeld’s signature wrestling move was a body slam. His preferred version, euphemistically called the “fireman’s carry,” is neither subtle nor delicate, a creature more of the Rowdy Roddy Piper school of bruising than the staid and honorable Greco-Roman tradition. Throughout his successful wrestling career in high school, at Princeton, and in the Navy, Rumsfeld used the move to great effect; it made no difference that his opponents knew it was coming. “He was the most aggressive wrestler I ever saw,” said a teammate who was struck by the way Rumsfeld would tear into the other guy from the whistle. One is tempted to divine from this an allegory for the future defense secretary’s famously confrontational personality and management style, but it seems better merely to observe that of course this is how Donald Rumsfeld would wrestle. You should see him play squash.

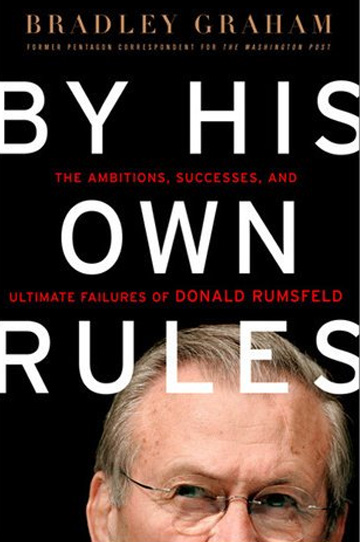

Ah, Rummy. How mundane and predictable our public affairs have become without him! Unlike Vice President Cheney, Rumsfeld has lately been absent from public view. He has not broken ranks with President George W. Bush, disowned the State Department, or taken the podium at safely unquestioning think tanks to criticize the new president’s stewardship of the national defense. It does not diminish one’s despair of Rumsfeld’s catastrophic tenure at the Pentagon to observe that there is a measure of class in this. Two and a half years have passed since his dismissal as defense secretary, and even if new — and festering — crises now occupy our full attention, the time seems right to revisit him. Bradley Graham of the Washington Post has written the first serious biography, By His Own Rules, which is full of revealing anecdotes and insights, even if its sources are the usual Beltway backstabbers and its coverage tends to be broader than it is deep.

The wonder is that this is the first such book, for what biographer could resist so intriguing a subject? That ferocious squint; those performance-art press conferences; the busy hands; the rapid-fire memos (“snowflakes”); the bureaucratic tricks, like getting poor Colin Powell riled up before Cabinet meetings; the breathtaking arrogance and contempt for journalists and naysayers that hovered around the secretary like the very fog of war — this is the stuff of a biography. Rumsfeld is a colossus, Wagnerian in his ambition, personality, and, ultimately, his failure, and he is worth trying to understand. Although the best assessment of his impact will come from historians, this is a very good start.

Younger readers will be struck by the precociousness of a man they have known only as a crusty old soldier. Rumsfeld successfully ran for Congress at 29, supporting civil rights, opposing the Vietnam War, and helping to draft the Freedom of Information Act. He threw his weight behind Representative Gerald Ford in a party leadership struggle, a move that would improbably pay off years later when President Ford invited Rumsfeld to serve as chief of staff and then as the youngest defense secretary in history. Before that, Rumsfeld had left his job as counselor to President Nixon in 1972 to take the post of U.S. ambassador to NATO, putting him safely in Brussels when the Watergate gong sounded.

Although it is easy to write off the NATO move as lucky timing, Rumsfeld has displayed a lifelong probity that may explain his distance from Nixon’s worst excesses. Graham is perhaps too hard on his subject in explaining this streak as a politically calculated effort to avoid scandal, for it lasted well throughout Rumsfeld’s second stint at the Pentagon, which he surely knew was his last job. In one of the book’s most fascinating passages, Graham excerpts a memo showing that Rumsfeld insisted on reimbursing the government for every personal flight, paid for his own meals, and, just in case he missed something, wrote an annual check to the Treasury for $5,000. He also avoided conflicts of interest between his former business career and the moneybag defense contractors who wooed his department. If ex-Halliburton CEO Cheney was both corrupt and awful, Rumsfeld was just awful.

Three bona-fide calamities will forever be associated with his name: the decision to invade Iraq, the mismanagement of that war’s aftermath, and the torture of prisoners by American personnel. Graham is sufficiently critical of Rumsfeld as to the latter two, but not the first. Rumsfeld was not the loudest proponent of war, but he certainly did his bit, and, perhaps more important, hired and supported duty-free dreamers like Paul Wolfowitz, Douglas Feith, and Richard Perle. He ignored the State Department’s postwar planning advice and displayed an unshakable commitment to trimming the armed forces, even as it became clear to everyone else that more troops were needed in Iraq. (The “surge” has largely vindicated his critics’ view.) And on torture, Graham echoes others who have convincingly drawn a line from Rumsfeld”s approval of “harsh interrogation methods” for Guantánamo detainees to that man standing on a box with wires running from his hands. The Economist put it best when its cover featured that photograph under the text, “Resign, Rumsfeld.”

Surprisingly, this most unequivocal of men emerges from his own biography as a walking contradiction. Rumsfeld was a radical reformer who approached change cautiously, and an arrogant jerk who charmed in polite company. He terrorized his underlings but hadn’t the heart to fire anybody. He delegated and micromanaged. The biggest contradiction, though, is not one that Rumsfeld embodies but one that he inspires. Looking back now at the famous picture of him scowling dangerously as he strode through Iraq in his dusty combat boots, it’s hard to shake an involuntary sense that he is exactly the kind of warrior — fearless, aggressive, a fighter, not a uniter — we want guarding the wall when the next attack comes. It feels both shameful to admit this and dishonest not to. And yet if that is the secret instinct, experience now tells us what a giant mess of things such a person can make.