Michael O'Donnell

Reader, Writer

Hiding in Plain Sight

April 26, 2014 | The Wall Street Journal

THIS DARK AND SOBERING book tells the life of Duncan Lee, attorney, intelligence officer, descendant of Robert E. Lee – and Soviet spy. Lee was an impeccably pedigreed member of one of Virginia’s oldest families and a Cold Warrior who undermined Mao’s communists on behalf of the CIA. But his bona fides masked a radical past. While working for the CIA’s predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services, Lee passed political intelligence to the Russians for nearly three years during World War II. And he got away with it. Duncan Lee died a free man in 1988, having never been arrested or convicted of any crime.

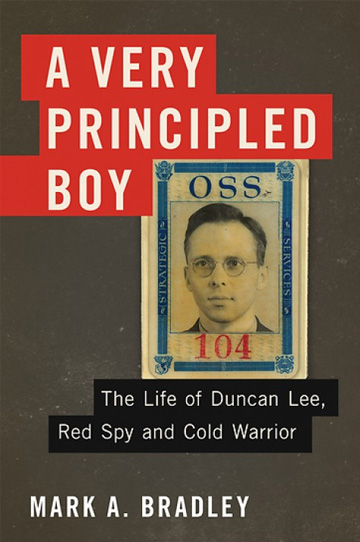

In “A Very Principled Boy,” Mark Bradley tells Lee’s story with few frills or atmospherics, letting the remarkable facts speak for themselves. Mr. Bradley is a former CIA intelligence officer whose straightforward narrative refuses to sensationalize. For this and other reasons, it radiates authenticity: There is little cloak . and dagger, no fog at all, and the tone conveys riot excitement and adventure but unease and doubt. As Mr. Bradley writes in the book’s introduction, Lee’s life exemplifies “the morally shaded, highly compartmentalized black, white, and gray worlds that spies inhabit.”

Lee’s formative experience was a Rhodes Scholarship in 1935-38. At Oxford his leftist outlook and inherited idealism (his parents were missionaries) found purchase in campus politics. Mr. Bradley describes the appeal of the U.S.S.R. to a young man of that era: “The Soviets seemed to have established a genuine workers’ government. They had also assumed the leadership of the world’s life-or-death struggle against international fascism. The Soviet Union in the 1930s offered a shining alternative to the United States, with its Hoovervilles, park sleepers, demoralized farmers, and joyless youth.” The cost of communist utopia was of course widespread terror and economic ruin. But while Stalintore his country apart with show trials and purges, Lee praised his “strong arm” in letters home to his parents.

Radical or no, Lee had not set out to betray his country. “There is no evidence,” Mr. Bradley writes, “that the Soviets asked him to apply to the OSS.” A model of bourgeois aspiration, Lee earned a degree at Yale Law School and joined a Wall Street firm in 1939. But by a quirk of history its chairman was William Donovan, whom Franklin Rooseveltwould choose two years later to lead the United States’ first free-standing civilian intelligence organization.

Here Mr. Bradley is a little too bland: “Wild Bill” Donovan, a legendary and controversial figure, was an Irish Catholic Anglophile, womanizer and fearless combat veteran. He was as titanic a character as his chief bureaucratic rival, J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI. Yet while Mr. Bradley devotes pages to Hoover’s idiosyncrasies and paranoia, his Donovan is too vanilla. Rather than recruit a professional corps of intelligence agents, Donovan picked men for their backgrounds, favoring pedigreed blue bloods. Lee made the cut, following Donovan to the OSS and working his way up to chief of the Secret Intelligence Branch before the OSS disbanded in 1945.

The NKVD spotted a bonanza: a smart young communist at the heart of America’s budding intelligence establishment. It cultivated and turned him through an agent based in the Communist Party USA—Mary Price, who became Lee’s lover as well as his first handler. Lee fed her wartime intelligence, such the Allies’ secret condition for opening a second front against Germany (a Russian declaration of war against Japan). In a decision that saved his life, Lee refused to copy documents, instead memorizing them and reciting them to Price. But the NKVD soon replaced her with the woman who almost brought down Lee and the Soviets’ entire network in the United States: Elizabeth Bentley.

An unpredictable alcoholic who clashed with the Soviets about money and methods, Bentley was an accident waiting to happen. Lee gave her secrets, but spying had taken its toll on him. Guilt over what he had done and fear of execution destroyed his nerves as well as his marriage. He got out. And just in time: In 1945, Bentley defected to the United States. Mr. Bradley’s chapter on this pivotal moment is the most riveting in the book. The NKVD’s man in New York recommended murdering her, only to be overruled by Lavrenty Beria, the head of the NKVD. Bentley went to the FBI, testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee, and signed written statements naming some 150 Soviet agents in the United States government. Lee was one of them.

The ensuing cat-and-mouse game between Lee and Hoover’s FBI forms the remainder of the book. The government lacked enough evidence to prosecute Lee for espionage, or even for perjury after he denied Bentley’s claims before Congress. It was her word against his, and no jury would believe Bentley, an unstable witness who was also a professed former communist. In 1950 the predecessor to the National Security Agency confirmed Bentley’s charges about Lee through intercepted signals traffic. But the FBI was unwilling to disclose the eavesdropping program in court and maddeningly had to stand by while a known traitor lived comfortably as a corporate attorney.

For the rest of his life Lee dismissed Bentley’s charges as the ravings of a lunatic. The most troubling pages of “A Very Principled Boy” concern a document Lee wrote near the end of his life: “The Elizabeth Bentley Matter (A Memorandum to My Children).” In it he flatly denies having spied for the Soviets. That a man would stare into the faces of his children and lie to them is a haunting example of the outer limits of deceit.

If those are the personal costs, what about the broader ramifications of Lee’s treason? In his defense, he passed political rather than military intelligence and passed it to a nominal ally rather than an enemy. Yet by the mid-1940s the Soviet Union was shaping up to be America’s chief rival. Lee gave the Russians a window into American intelligence’s personnel and methods. Domestically, his case helped pave the way for McCarthyism and HUAC’s witch hunts. As Mr. Bradley nicely puts it: “The existence of real spies in the 1940s had created lifelike mirages of them by the early 1950s.”

One finishes this fascinating narrative wondering whether Duncan Lee regretted what he had done. His steadfast denials made any sort of reckoning impossible. And there are no answers in his ghost-like face either. Closing the book on a portrait of him in uniform during his spying years, the reader cannot recall whether he was smiling or serious, if he had any distinctive features, or if he was even there at all.