Frontier in the Clouds

May 26, 2022 | The Wall Street Journal

Mount Everest has become such an overcrowded playground that the best way to experience the mountain itself may be to go back in time. Covered in refuse, empty oxygen bottles, even human remains, the peak now sees hundreds of summit attempts each spring, paid by fees of some $50,000 per client. With crowding comes tragedy, such as an avalanche in 2014 that killed 16 Sherpas and an earthquake in 2015 that claimed as many as two dozen climbers. As Jon Krakauer wrote in “Into Thin Air,” his account of a 1996 Everest catastrophe in which eight people died, such losses have become “simply business as usual.”

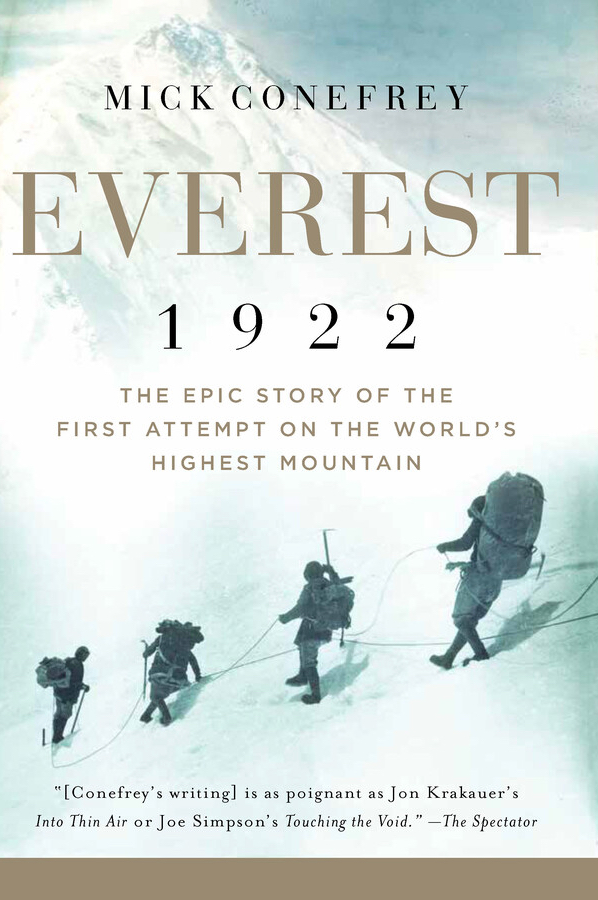

In “Everest 1922,” the British mountaineering historian Mick Conefrey goes back to the beginning. The book is a nuanced, highly readable chronicle of the first attempt on the summit 100 years ago. It was an age when alpine teams made their own base camps and relied on their own surveying skills to confirm that they had the right peak in front of them. The Himalayas were an unknown frontier, and Mr. Conefrey captures the awe that adventurers felt in their mighty company. After George Mallory, remembered as the party’s most famous member, glimpsed Everest through a break in the clouds, he described “a prodigious white fang excrescent from the jaw of the world.”

The expedition took place in the aftermath of World War I and in the shadow of journeys to the North and South poles. It was “BAT”—British All Through—launched under the auspices of the Royal Geographical Society as well as the Alpine Club. The English flavor was partly a result of the imperial spirit of the day, characterized by a bottomless appetite for conquest. And partly it was a question of access through India, controlled by the British Empire. A key moment in the planning occurred when the Dalai Lama granted permission to travel through Tibet to reach Everest from the north. (Today, despite a new Chinese highway in the area, it is still most often approached from Nepal, in the south.)

The Alpine Club put together its team. Female applicants were laughed from the room with galling callousness. Physical exams weeded out those who lacked the constitution for the journey, such as one man whose mouth was found “very deficient in teeth.” Funding came from donations—the Prince of Wales gave £50—as well as the sale of newspaper rights in the story. Fortifications for the undertaking included tins of spaghetti, Irish stew, quail in foie gras, turtle soup, marmalade, mint cake, over 20,000 cigarettes and quite a bit of Champagne.

Mr. Conefrey chronicles the two distinct campaigns that followed: a reconnaissance mission in 1921, and the climb itself the following year. Mallory was the only common member and arguably the strongest alpinist, yet he comes in for a humbling treatment after generations of mythologizing. The former soldier and schoolmaster is presented here as careless, petty, monomaniacal, vainglorious, technophobic and, worst of all, bored by the lovely people and landscapes of Tibet. Yet Mr. Conefrey also does justice to Mallory’s eloquence and his heroism, such as his quick work with an ice ax during a fall that likely saved several team members’ lives.

The reconnaissance group had to survey the mountain and find a route up it. They trekked through the “sand dunes, mud flats and walled towns” of the Tibetan interior, visiting monasteries and taking photographs. “Today, Everest is one of the most well-mapped mountains in the world,” Mr. Conefrey writes, and its glaciers and features (the Khumbu icefall; the Hillary step) are well-known to readers of mountaineering lore. “In 1921, however, none of this was known to the British team.” Eventually they plotted a workable route and made it as high as the North Col, at approximately 23,000 feet, when a combination of thin air and fierce wind forced their retreat. “It was a pitiful party at the last,” Mallory wrote, “not fit to be on a mountainside anywhere.”

The effects of altitude were not well understood a century ago. Yet one member of the 1922 climbing team, the Australian chemistry lecturer George Finch, appreciated its dangers. Finch led the drive to bring bottled oxygen, facing opposition from Mallory and others who found its use a “damnable heresy.” Self-confident and unclubbable, Finch was at bottom no Englishman; he and Mallory detested each other. Yet Finch, whom Mr. Conefrey champions, proved a skilled problem solver and a forward thinker. He courted mockery by bringing a down suit where the other party members wore pitiful woolen scarves and waistcoats; the assembly resembled a “Connemara picnic surprised by a snowstorm,” in the words of George Bernard Shaw.

The 1922 team made three attempts on the summit. Mallory led the first, Finch the second, and the third was a joint effort. The legendary bulldog Charles Bruce organized matters from base camp. (“Hurry up with that thousand please,” he wrote to London, briskly demanding more funds.) Mallory’s group faced bad weather and climbed without oxygen or crampons. Finch, by contrast, breathed freely and pushed higher, to 27,300 feet, but decided to turn back in deference to a weaker partner. The third attempt represented the triumph of ego and rivalry over good sense, and ended when an avalanche killed seven porters. Team members infantilized the porters and the Sherpas, although they quickly proved adept climbers well-suited to the low-oxygen environment. Failure hung over the group when it returned to England, for all that it had achieved.

Beyond telling this overlooked story with verve and precision, Mr. Conefrey shows how the 1922 expedition anticipated many of the preoccupations of modern mountaineering. Like many Everest dramas, it ended in tragedy. The debate over bottled oxygen continues, and stands in for a broader split between huge assault-type expeditions and the “fast-and-light” alpine-style of climbing now ascendant. And the big-ego rivalries of alpha males vying to outdo each other on the mountainside are ever familiar.

Yet whether the great Mallory ultimately beat his nemesis Finch is a matter of perspective. Mallory is thought to have climbed higher on a subsequent trip to Everest, in 1924. But he died on the mountain, whereas Finch lived comfortably to the age of 82.