Less than Zero

April 1, 2005 | Bookforum

April 17, 1975, was one of the most bizarre and horrifying days in modern history. Single-file lines of expressionless soldiers, armed to the teeth and clad in black, marched into Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia, and began ordering its inhabitants at gunpoint to evacuate the city. The soldiers, known as Khmers Rouges, summarily execuated hundreds of government loyalists and then forced the capital’s 2.5 million inhabitants into the countryside, where, over the next three and a half years, they became zombies, toiling in the rice fields and babbling revolutionary doctrine. Some twenty thousand died on the journey out of the city; by some counts, as many as two million ultimately perished under the regime that seized power that day. It was the beginning of”the world’s most radical revolution.”

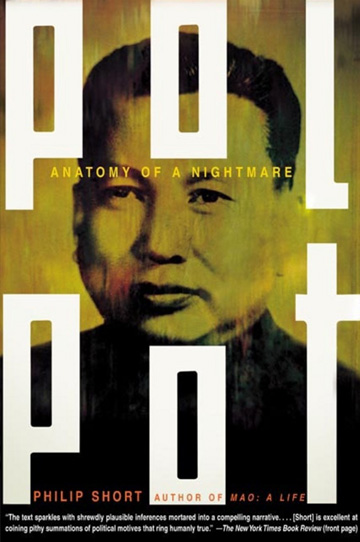

The riveting chapter on the fall of Phnom Penh alone makes Philip Short ‘s biography of Pol Pot, the enigmatic Khmer Rouge leader who masterminded the evacuation and became Cambodia’s dictator, worth reading. A former BBC correspondent, Short published in 2ooo what has been lauded as the authoritative biography of Mao Zedong, and he writes in the punchy, confident tones of a journalist with a great scoop and the verve to tell it. In Pol Pot: Anatomy of a Nightmare, he has drawn on hundreds of hours of interviews with former Khmer Rouge leaders, as well as documents in Khmer, Chinese, Russian, French, and Vietnamese, to produce what is certainly one of the most important–and thoroughly readable–works on Pol Pot and modern Cambodian history.

Short moves briskly through Pol’s boyhood as Saloth Sar, the son of well-off parents and a mediocre student, to his formative years at a French engineering college, where he was known as a bon vivant who was quick to smile. In Paris he met a host of progressive Cambodian students whose evening political discussions were at first unfocused and divorced from reality–“rather muddled,” in Short’s polite British.

But under the leadership of future Khmer Rouge foreign minister Ieng Sary, who was severe and disciplined, the Cercle Marxiste gradually found its purpose in unseating the hated French-collusionist regime of Prince Sihanouk in Phnom Penh.

Sar was not, however, in the vanguard of the revolutionary students at first: “If Saloth Sar remained inconspicuously in the background for his first two years in Paris, it was partly his character–as he put it many years later, ‘I did not wish to show myself’–and partly because he had yet to find his role. He breathed the ‘air of the times,’ as the French expression has it, and was carried along, with little effort on his own part, by more assured, dynamic colleagues .. .. [H]e found [the circle] fascinating, but the discussions were often above his head.”

“Something clicked,” though, when in 1951 or ’52 Sar discovered the writings of Stalin–less heady than Marx and Lenin, and more accessible for their pragmatic emphasis on an elite party leadership and constant vigilance against traitors. Sar became passionate for the first time in his life. He had found his purpose: “It was revolution.” The nascent Khmer Rouge leadership returned to Cambodia and entered the jungle to study guerrilla warfare with the Vietnamese.

Over the next twenty years, the Khmers maintained an uneasy alliance with Vietnamese troops in a civil war against Sihanouk and his successor, Lon Nol, that was marked by barbarism on both sides. Meanwhile Sar moved up the ranks to become the leader of the resistance, changed his name to Pol Pot, and solidified the Khmer Rouge ideology. Influenced more by the French Revolution than by 1917 Russia or 1949 China, and with “an unschooled, almost mystical approach to communism,” he and his cohorts freely ignored fundamental tenets of Marxist orthodoxy. Cambodia’s population largely consisted of peasants, and there was little industrial proletariat to speak of–the “landscape, and the lifestyle, were, and are still, closer to Africa than China”–but no bother. Pol’s solution, amazingly, was to refuse to admit workers to his newly founded Communist Party and, drawing on his spiritual roots in Buddhism, to cultivate instead a “proletarian consciousness” in all Cambodians by making peasants of them. In one cadre’s words: “Zero for him and zero for you–that is true equality.”

At home, Pol turned daily life into a nightmare of collectivization and killing. All peasants were forced to wear black, as they labored to increase Cambodia’s agricultural production while starving because of the meager rations served in communal barracks. Money, private weddings, memories of pre-revolutionary life–even laughter, in some villages–were prohibited. Cambodians were subjected to a ruthless brainwashing campaign, based on the principle that minds were “mental private property” and as such impeded true collectivization. Hundreds of thousands of Cambodians were branded enemies for flouting rules, or simply for being insufficiently joyful about their new life, and were executed with cudgels and pickaxes when a machine gun wasn’t handy. It was not, however, a genocide, Short contends–a not altogether persuasive challenge to the conclusions of academics like Ben Kiernan and Samantha Power. For although certain groups, such as ethnic Vietnamese and Muslim Chams, “had special difficulty in accommodating to the new regime” (as Short puts it quite mildly), the goal was uniformity, not the extermination of individuals based on their ethnicity or religious beliefs.

Abroad, Pol struggled from the outset with the Vietnamese Communists, who had designs on a unified Indochinese state but whose plans often came at the expense of their Cambodian little brothers. Pol’s incendiary anti-Viemamese rhetoric led to clashes with Vietnamese troops and, eventually, a Vietnamese invasion that toppled the Khmer Rouge, in 1979. He spent the remainder of his life trying in vain to regain power.

The reader of Anatomy of a Nightmare will quickly recognize the author’s expertise on Chinese politics. Short is at his best when describing the historic meeting between Pol and Mao in r975, in which the chairman’s elliptical way of speaking and implied meanings were all but lost on Pol in the translation from Mao’s halting English into Khmer. Mao was old and frail, Short writes, but his “mind was as nimble as ever. The Cambodian communists intrigued him …. The one idea that clearly did resonate, because afterwards Pol frequently repeated it, was Mao’s injunction to his visitors not to copy indiscriminately the experience of China or any other country, but ‘to create your own experience yourselves.'” Short also provides an especially lucid description of the precarious minuet involving Cambodia, China, and Vietnam in the 197os and ‘8os. China became Cambodia’s patron in an effort to stem the tide of Vietnamese–and hence Soviet–communism, supplying arms and even going so far as to take up fighting on behalf of the Khmer Rouge during the Vietnamese onslaught.

China was not, of course, the only powerful nation to use Cambodia as a proxy for cold-war advantage. While the United States pulled itself out of Viemam, President Nixon ordered more than seventy thousand US and Vietnamese troops into Cambodia and dropped five hundred thousand tons of ordnance on Viet Cong and Khmer Rouge outposts, killing a half-million people. During the ’50s, the US government tacitly approved Vietnamese attempts to assassinate Prince Sihanouk, and from 1970 to 1975 it propped up Lon Nol’s corrupt regime as a bulwark against the jungle Communists. After the Khmer government fell, the United States lobbied at the United Nations for the Khmer Rouge to maintain Cambodia’s seat while Pol bled the Vietnamese in a simmering war to regain control. While Pol was in power, though, the United States closed its eyes. The Ford and Carter administrations were unwilling to return to Southeast Asia, and American leftists like Noam Chomsky, convinced that the United States and not the Khmer Rouge was the source of Cambodia’s problems, shamefully downplayed the horrifying stories of Cambodians, emphasizing “the extreme unreliability of refugee reports.”

One of Short’s weaknesses is that his focus on Cambodian politics and history, rather than Pol’s daily life, makes this feel at times unlike a biography at all. But this is explained, at least in part, by Pol’s extraordinary penchant for secrecy. For evidence of this, look no further than the photographs in Pol’s biography-most of them are of other people, as only several grainy shots from the first half of his life exist. The book brims with other examples of Pol’s elusiveness. Over the years, he made several important strategic decisions in concert with Prince Sihanouk (an improbable ally after his fall from power in r970), but he always did so using intermediaries or ghost names, so that years later, when Sihanouk learned that Pol had been involved, the deposed prince was flabbergasted. The Cambodian people were not even aware that their new overlords were part of a Communist government for almost a year and a half after the Khmer Rouge had seized power.

What made Pol a monster? Short describes a tableau of factors. Perhaps foremost was the influence of Buddhism, starting with a strict year for Pol in a Phnom Penh monastery when he was a boy. With its emphasis on absolute obedience and the stamping out of individuality, Theravada Buddhism directly influenced the nightly “criticism and self-criticism” sessions in which peasants confessed their daily unrevolutionary acts and pointed out others’ shortcomings, systematically breaking down all ties to the personal and the private. Short also explores a culture in Cambodia that has long stomached shocking acts of brutality in daily life, as well as the country’s perpetual humiliation at the hands of other nations. But there can be no simple explanation for the descent into madness that was Pol’s apogee. Anatomy of a Nightmare makes for chilling reading. Would that Short could chronicle all our tyrants.